Editor’s Notes - About halfway through this essay I refer to original research conducted with two forms of Lithasia on the Duck River, GEN and DUT. That work was published as a note in Ellipsaria 22(3) [pdf] if you are looking for something citable [1]. The present essay was subsequently published as: Dillon, R.T., Jr. (2023b) What is character phase disequilibrium? Pp 153 – 162 in The Freshwater Gastropods of North America Volume 6, Yankees at The Gap, and Other Essays. FWGNA Project, Charleston, SC.

It has come to our attention that some non-negligible fraction of our professional colleagues do not understand transmission genetics. I suppose I might have seen it coming. Over the 33 years I spent as a genetics professor at a mid-sized college of regional reputation, textbook chapters devoted to Mendel and Morgan became skinnier and skinnier, squashed by bulging chapters of molecular ephemera. Some of my younger colleagues seemed to consider that transmission and population genetics were epiphenomena, to be mentioned, perhaps, on the way to the subject matter that might actually be useful or interesting to the students.

So before launching into this month’s lecture, I am springing a pop quiz. Everybody please return with me to my November essay on Leptoxis. You can either scroll down below the lengthy January essay that follows and the (somewhat shorter) December essay below that or open this link in a fresh window [2Nov21]. Now read the four paragraphs about “the third important lesson” halfway through that essay, including footnotes #13 and #14, paying special attention to the material about “snail 5S.” When you get to “0.05^2 = 0.0025” in footnote #14, stop. If you understand the importance of that calculation, feel free to skip this month’s essay, and I’ll see you next month. But if all that stuff about snail 5S and its parentage is foggy to you, read on.

Gregor Mendel proposed his “second law” on the strength of an experiment he conducted in his pea garden using two genes: seed color (yellow/green) and seed shape (smooth/wrinkled). He interpreted the 9:3:3:1 phenotypic ratio he observed in the F2 from his dihybrid cross as the result of independent assortment of those two genes.

|

| From Lobo & Shaw [2] |

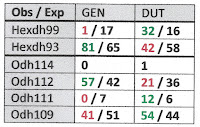

In Table 1 below I have combined the GEN and DUT samples collected at Wright Bend (site E) for a total of 2(78) = 156 haploid genomes [5]. Each haploid genome is classified jointly by the allele resolved at the Odh and Hexdh loci, with observed counts above the slash, and expected below.

Table 1 shows evidence of disequilibrium between the Odh and the Hexdh locus, with excesses of Odh112/Hexdh93 and Odh109/Hexdh99 association. The 3x2 contingency chi-square (setting aside rare allele Odh114) was 7.69, significant at the 0.05 level. This sample does not seem to have been collected from a randomly-breeding population.

And indeed, a similar analysis combining the 32 GEN individuals collected at Site D with 34 DUT individuals would yield similar results, and ditto again were we to combine the 33 GEN and 35 DUT individuals collected at Site F. The evidence suggests that this case of gametic phase disequilibrium is stable.

Now let’s generalize the situation one step further. The gametic phase disequilibrium documented in Table 1 is correlated with shell phenotype. It disappears when either GEN or DUT is analyzed separately, at all three sample sites. Lithasia bearing shells of the oblong-bumpy GEN phenotype demonstrate significantly higher frequencies of Odh112 and Hexdh93 than Lithasia bearing acute, angulate DUT shells at all three sites where they were collected together.

|

| Tab 1. Site E, GEN and DUT combined |

Shell morphology is a function of both genetics and environment, of course. Heaven knows that enough pixels have sacrificed their flickering lives to both those fractions of the variance on this blog [6]. But Table 2 shows that the component of shell morphological variation that Johnson, Ahlstedt and their colleagues used to distinguish GEN from DUT in 2002 is correlated with variance in two demonstrably genetic markers, Hexdh and Odh. And there is no apparent correlation between shell morphology and environment in this situation, whatever environmental variance there might have been within sites rendered negligible by the variance between.

Let us broaden the concept of gametic phase disequilibrium to include measures of the phenotype, shall we? Here I suggest a new term, “character phase disequilibrium” to describe situations such as documented in Table 2, where variation in the phenotype correlates with variation in the genotype. I define CPD as “any violation of independent assortment between one or more morphological characters and one or more characters of demonstrably genetic origin” [7].

The potential underlying causes of character phase disequilibrium are identical to the causes of the better-known gametic phase disequilibrium. In the case of the Lithasia of the Duck River, the cause of the disequilibrium between genotype and phenotype is almost certainly a violation of the assumption of random mating. But of what origin?

In natural populations inhabiting large and complex environments, the first thought of an evolutionary biologist would be that any observed non-random mating would arise from barriers to dispersal or simple isolation by distance, as we obsessed over on this blog from September to December [8]. And in fact, we have very thoroughly documented both phenomena in the Lithasia populations of the Duck River [1, 4].

|

| Tab 2. Site E, GEN and DUT separate |

Rather, the data suggest that the GEN subpopulation bearing bumpy, oblong, typical shells and the DUT subpopulation bearing acute, angulate shells are reproductively isolated biological species, at all three of the sample sites tested down a 120-mile length of the Duck River. The situation is apparently stable.

OK, coming off the backstretch now, heading for home. Let me ask you to do one more thought experiment with Mendel’s peas. For this experiment I will ask you to assume that peas are outcrossers, not selfers. And this time, plant a field almost entirely of green/wrinkled peas, with one single yellow/smooth pea planted in the center. Remember that seed color and seed shape are not physically linked, and this time your singleton yellow/smooth pea plant can freely cross-pollinate with its neighbors, as in a normal field of flowers. Would the two loci appear to assort independently?

The answer is no. I’ve asked you another trick question. I didn’t mention anything about the passage of generations.

Initially, standing on the edge of your newly-planted pea garden with your hands on your hips, seed color and seed shape appear to be tightly linked, because the only plant with yellow seeds has smooth seeds. And if you let your plants cross-pollinate, set seed, die, and bring forth a fresh generation, seed color and seed shape will still appear tightly linked, because every pollen grain made by your yellow plant was also marked with the smooth allele. All the yellow F1* will still have smooth seeds, remembering that both yellow and smooth are dominant. It might take quite a few generations [9] for the two loci, seed color and seed shape, to diffuse independently into the pea population before linkage disappears. But it will, eventually, disappear. This is unstable gametic phase disequilibrium.

And I am sure that my readership will have no difficulty extending the situation with the shell morphology in the Lithasia populations of the Duck into the pea garden of thought-experiment #2. If our mixed field of randomly outcrossing peas were to demonstrate variance in some morphological trait of unknown heritability, as well as variance in the two for which the genetic basis is well-documented, we would not be surprised to observe unstable character phase disequilibrium.

So finally. Character phase disequilibrium describes the situation with the singleton 5S snail that Nathan Whelan collected in his sample from the “Sixmile” Leptoxis subpopulation [10]. That snail simultaneously bore both the genetic markers and the shell morphology of the “Bulldog” population upstream. But is that disequilibrium stable or unstable? All those obscure calculations in footnotes #13 and #14 of my November essay were my efforts to answer that question.

|

| Detail from Whelan et al [10] Fig 2 |

But if my first thought were true, the genotype of snail 5S would be 50/50. The apparent excess of Bulldog genome made me consider the possibility that snail 5S might be an F2 or higher, with a pure Bulldog parent backcrossed to a second parent containing some Bulldog genome, which would be highly unlikely unless there were some reproductive isolation between Bulldog and Sixmile. In other words, the character phase disequilibrium at Sixmile might be stable. And the Bulldog and Sixmile populations have speciated? Really?

In retrospect, all that wheel-spinning in footnotes #13 and #14 of my November post was entirely unnecessary. One need only look downstream to Nathan’s Centreville sample, which was a melting-pot of Bulldog, Sixmile, Centreville, and other populations as well. The excess Bulldog genome in snail 5S is just slop, there is no evidence of reproductive isolation, the character-phase disequilibrium at Sixmile is unstable.- Lobo, I. & Shaw, K. (2008) Discovery and types of genetic linkage. Nature Education 1(1):139.

[3] This is a place-keeper footnote, which I will call up next month.

[4] Dillon, R. T., Jr. (2020) Population genetic survey of Lithasia geniculata in the Duck River, Tennessee. Ellipsaria 22(2): 19 - 21 [pdf]. For more, see:

- Intrapopulation gene flow: Lithasia geniculata in the Duck River [7Dec21]

[5] This is somewhat less than you might expect summing the locus totals published in [1], because for a few individuals I was able to obtain results at one locus and not the other. Data from both loci are required for the joint analysis shown in Table 1.

[6] If you hit the “Phenotypic Plasticity” label above right you will find (as of January 2022) no fewer than 28 essays touching on the heritability of shell morphology in freshwater gastropods. If I had to pick two, my favorite from the environmental side would probably be the first listed below, and my favorite from the genetic side would most certainly be the second, with the references cited in both:

- Pleurocera acuta is Pleurocera canaliculata [3June13]

- The heritability of shell morphology h^2 = 0.819! [15Apr15]

[7] We have also touched on the concept of character phase disequilibrium in several previous essays on this blog. An understanding of CPD was critical to my series on the cryptic Pleurocera of Maryville:

- The cryptic Pleurocera of Maryville [13Sept16]

- The fat simplex of Maryville matches type [14Oct16]

- One Goodrich missed: The skinny simplex of Maryville is Pleurocera gabbiana [14Nov16]

I didn’t call the phenomenon anything at the time because I thought that the concept of CPD was obvious and didn’t need a name any more than it needed an explanation. Looking back, my Maryville research demonstrated the power that an understanding of character phase disequilibrium can bring to evolutionary science. But maybe I should have posted the present essay back in 2016.

[8] Here is my series on gene flow within populations of freshwater gastropods:

- Intrapopulation gene flow: King Arthur’s lesson [7Sept21]

- Intrapopulation gene flow: The polymorphic Pleurocera of Naked Creek [11Oct21]

- Intrapopulation gene flow, the Leptoxis of the Cahaba, and the striking of matches [2Nov21]

- Intrapopulation gene flow: Lithasia geniculata in the Duck River [7Dec21]

[9] The number of generations required will be a function of both the rate of gene flow and the effective population size. In fact, the level of gametic phase disequilibrium observed is one of two methods by which the effective size of a population can be estimated. For more, see:

- The best estimate of the effective size of a gastropod population, of any sort, anywhere, ever [14Jan19]

[10] Whelan, N. V, M. P. Galaska, B. N. Sipley, J. M. Weber, P. D. Johnson, K. M. Halanych and B. S. Helms (2019) Riverscape genetic variation, migration patterns, and morphological variation of the threatened Round Rocksnail, Leptoxis ampla. Molecular Ecology 28:1593-1610. For a review, see:

- Intrapopulation gene flow, the Leptoxis of the Cahaba, and the striking of matches [2Nov21]