Editor’s Note – This essay was subsequently published as: Dillon, R.T., Jr. (2023c) In the Footsteps of the Comte de Castelnau. Pp 287 – 296 in The Freshwater Gastropods of North America Volume 7, Collected in Turn One, and Other Essays. FWGNA Project, Charleston, SC.

Way back in September of 2020 I concluded a mundane essay about juvenile shell morphology with the following deceptively difficult question: “What, exactly, are Helisoma scalare and Helisoma duryi?”

Over the four months and five essays that followed [1], we were able to establish that both taxa are big Floridian planorbids, sometimes assigned to the genus “Planorbella” for no reason whatsoever [9Sept20], set aside in a subgenus Seminolina by Henry Pilsbry [2] in 1934 [3Dec20]. The difference between the two nominal species lies in the shell coiling, Helisoma scalare being distinguished by a peculiar flat-topped “scalariform” morphology. Helisoma duryi, on the other hand, usually bears shells of the typical planispiral type, so typical, in fact, that they are often very difficult to distinguish from those borne by dirt-common Helisoma trivolvis populations widespread across the rest of North America [5Jan21].

Ultimately, however, I only answered half of the question I posed in September of 2020. Across the six total essays I posted on the subject, I spent 50% of my time obsessing about Helisoma duryi, focusing especially on their protean variability in shell morphology, “short, fat, tall, skinny, and all over the place” [5Jan21]. Then I spent 30% of my time obsessing about Helisoma trivolvis and 20% of my time obsessing about Henry Pilsbry [26Jan21], never really touching on Helisoma scalare at all. So, this month let’s back up and get a fresh start at the scalare half of the question, shall we?

|

| P. scalaris, holotype [4] |

Jay’s holotype (AMNH 56111) is still held by the American Museum of Natural History today [4], looking just as dramatically flat-topped as Jay figured it in 1839. Jay’s nomen “scalaris” or scalare [5] is the sixth oldest nomen applied to any of the large [6] North American planorbids, after trivolvis, glabratus [7], campanulata, corpulentum and anceps.

But if there is one lesson I have learned over my many months, indeed years, of struggling with the taxonomy of Florida freshwater gastropods, it is that “The Everglades” is a big place. In our essay of [5Oct20] we learned that the Everglades Ecoregion, as formally defined by the Feds, extends over all or part of 18 South Florida counties, some 7,800 square miles. And in our essay of [3Dec20] we learned that when Charles Dury told Albert Wetherby that he collected a sample of planorbids in “The Everglades of Florida” in 1879, he meant in Volusia County, a couple hundred miles north of anyplace that the Feds would call Everglades today. What was “The Everglades” to a French Count in 1839?

Fortunately, Henry Pilsbry left us a very helpful clue in 1934, just as he did with Wetherby’s duryi. Quoting the Elderly Emperor verbatim [2]:

“Jay's locality was ‘Everglades of Florida, presented to me by Count Castelneau;’ that is, le Comte Franqois (or Francis) de Castelnau, who travelled in the southeastern states in the thirties and early forties. He published several papers in Bull. de la Soc. de Giographie, 1839-1842, in the last (vol. 18, p. 252) alluding to his work on Florida, which I have been unable to find in Philadelphia libraries. Probably the type locality can be recovered by looking up Castelnau's itinerary in this book.”

So here in the 21st century, Count Castelnau’s papers [8] are much easier to get hold of than they were in 1934. And even better, in 1948 a University of Florida historian named Arthur R. Seymour translated Castelnau’s work into English and republished it in The Florida Historical Quarterly [9]. And it materializes that when Castelnau said “The Everglades,” he meant the Florida panhandle, somewhere around Tallahassee.

Castlenau left Charleston, my hometown, in mid-November 1837, travelling first by rail to Augusta, then on “a very narrow and detestable road” through the heart of Georgia. His most interesting adventure southbound took place in the “ramshackle” [10] village of Bainbridge, where “about one hundred Chattahoutchi Indians, who are allies of the whites, arrived bringing with them about sixty hostile Creeks or Muscogis.” The Count was invited to join the Chattahoutchis for “an entire night of dancing, drinking and shouting.”

The Count arrived in Tallahassee after two weeks on the trail, exploring about the vicinity until mid-March of 1838, leaving us vivid accounts (and not a few interesting illustrations) of the small town and its environs, before returning to Charleston by way of steamer up the Apalachicola/ Chattahoochee River. But alas, at no time in any of his writings did he address the most important subject, the snails he encountered along the way.

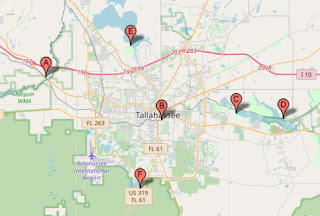

And so it came to pass that in February of 2021 I pointed my trusty [11] Mazda pickup south on I-95, Arthur Seymour’s translation of Castelnau’s travelogue on the passenger seat, outward bound on yet another planorbid-themed adventure. My plan was to visit every body of water mentioned by The Count in his Florida explorations, or at least representatives thereof, searching for a topotypic population of Helisoma scalare (Jay 1839). In the account that follows, I have interleaved quotes from Castelnau’s travels with notes from my own fieldbook.

We passed over the Oclockone [Ochlockonee] River and the Little River whose banks are delightful, then finding again pine woods we reached in the evening Tallahassee, the end of our [outbound] trip.

The Ochlockonee is what I would call (from my Carolina Lowcountry perspective) a typical blackwater river. I launched my kayak at the boat ramp under the US90 bridge (A) and paddled upstream around the bend and could find very little habitat for freshwater gastropods of any sort – no submerged or floating vegetation, indeed almost no vegetation at the margins.

Numerous springs exist in the neighborhood and from one of them comes a pretty stream of water that after having wound around the eastern part of the city [Tallahassee] runs into the forest and forms a charming waterfall about sixteen feet high; it runs then into a ravine hollowed out of limestone and disappears underground quarter of a mile farther.

It is not uncommon in this part of the world for cities to have been founded around notable springs. Huntsville and Tuscumbia, Alabama, come to mind in this regard. In both of those cases, city fathers have set aside parkland in the heart of the modern city and added all manner of improvements to the springs, sometimes (in some cases, maybe) preserving some ghost of the native macrobenthos in the process. Alas, the greatest disappointment of my fieldtrip came early, as I arrived at Tallahassee’s midtown “Cascades Park” (B).

|

| Cascades Park |

The montage above shows the modern park, with Castelnau’s original 1837 figure in the upper right corner. Notice the landscaping beds around the modern spring run, specifically designed to discourage park visitors from approaching the water. Little signs have been placed at the front of those beds, warning us (and our pets) not to enter the “stormwater.” And alas, that is indeed a stormwater sewer at the red arrow in the photo above, the water emanating from which bears a dark, suspiciously-olive color. I spent about 10 – 15 minutes poking around the water in desultory manner, picking up Physa, and moved on.

To the east of this town extend the lands offered by the government of the United States to General Lafayette in which is a pretty lake that bears his name. No words can convey the beauty of these sheets of water which scattered in great numbers in the midst of virgin forests in Middle Florida; they are filled with fish of many sorts and their surface is everywhere enlivened by clouds of aquatic birds, above which flies constantly the bald eagle. Among the denizens of these lakes we must mention the soft shelled turtles, as well as the alligators that are abundant there; these last reach ordinarily length of twelve feet, and although little to be feared, by their repulsive aspect they inspire terror in persons not accustomed to seeing them.

The Federal Government did indeed grant the Marquis de Lafayette a 36-square-mile tract east of Tallahassee in 1824, in gratitude for his military service to our young republic. Lafayette never visited, however, and the entire grant had been sold off piecemeal by 1855. The Lake Lafayette to which Castelnau referred was divided into three sections with dikes, its central section dredged for recreational use, and given the odd name “Piney Z” Lake, in honor of a nearby plantation.

|

| Lower Lake Lafayette |

I visited both the central Piney Z Lake (C) and Lower Lake Lafayette (D) at the town of Chaires. The former was warm and trashy, and hosted but Physa and Pomacea maculata. I had great hope for the latter, however, which I found to be a Lake in Name Only (“LINO”), choked with aquatic vegetation of all sorts. Indeed, I enjoyed one of my prettiest paddles in recent memory, spoiled only by the thunderstorm evident on the horizon of the photo above. And the malacofauna, which comprised nothing but Physa and Pomacea, again.

Lake Jackson is situated a league and a half [north] from Tallahassee. According to the Indians, its water gushed forth suddenly from under the ground, covering a vast cultivated plain. It is certain that trees are still to be seen there, and that when the water is low Indian trails may be noticed.

The hydraulics of Lake Jackson are indeed strange. The water level appeared at least ten feet below bank full on the morning I visited at site (E), boat ramps high and dry. I asked a local angler if this little patch of Florida might be suffering a drought, even as rainstorms daily drenched the remainder of the Sunshine State, coast to coast. He replied in the negative, explaining that the Lake has a small “closed basin,” and had gone entirely dry on several occasions in his lifetime. I thought (to myself) that a closed basin might rather lead one to expect high water in times as diluvian as those we were currently experiencing.

|

| Lake Munson |

A great number of lakes or ponds are scattered to the south of Tallahassee. All these lakes are surrounded by dense woods, which are scattered some fine cotton and sugar plantations. Most of them seem to be sinking leaving on their shores a great deal of fertile land. are often almost entirely covered with rushes and plants. In their water are found great numbers water serpents (mocassins), soft-shelled turtles, gators, among which swim large flocks of aquatic their shores are crowded with bands of deer and many white headed eagles soar over them or the oaks and the immense magnolias that are shores.

Lake Munson is a good representative of a “lake scattered to the south of Tallahassee.” I paddled around its west edge to no effect. But at the outlet dam (F), I was pleased to discover a healthy population of Helisoma. I was simultaneously disappointed, however, by the typical, planispiral shells they bore upon their backs. None, alas, demonstrated the “scalariform” shell morphology that made John Clarkson Jay’s Paludina scalaris so distinctive.

As the sun set on a long, wet day touring the diverse rivers, springs, lakes and ponds of Tallahassee and vicinity, I admit to experiencing a bit of frustration. True, I had found a couple scrappy populations of Helisoma. But none bore shells even remotely matching Jay’s 1839 type specimen in the collection of the American Museum way up in New York City. Were my hopes to be blighted? Stay tuned!

|

| Lake Munson at the outlet |

Notes

[1] Here is my complete series on Helisoma duryi and the flat-topped Helisoma of Florida to date:

- Juvenile Helisoma [9Sept20]

- The flat-topped Helisoma of The Everglades [5Oct20]

- Foolish things with Helisoma duryi [9Nov20]

- The emperor speaks [3Dec20]

- Collected in turn one [5Jan21]

- Dr. Henry A. Pilsbry was a jackass [26Jan21]

[2] Pilsbry, H. A. (1934) Review of the Planorbidae of Florida, with notes on other members of the family. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 86: 29 – 66.

[3] Jay, J.C. (1839) A catalogue of the shells, arranged according to the Lamarckian system; together with descriptions of rare species, contained in the collection of John C. Jay, M.D. Third Edition. Wiley & Putnam, New York.

[4] I thank Ms. Lily Berniker of the AMNH for her prompt and courteous attention to my request for this photograph.

[5] Pilsbry [2] re-spelled Jay's (feminine) scalaris to the neuter scalare to agree with the gender of the neuter noun construct Helisoma. I thank my good buddy Harry Lee for this insight.

[6] Pilsbry divided all the North American Planorbidae into two subsections, the large ones and the not-large ones [5]. John Clarkson Jay’s scalaris is the sixth oldest name for a large one. There are also five older names for not-large North American planorbids, which do not concern us here, but for the record: parvus, deflectus, crista, armigera, and exacuous.

[7] Thomas Say gave the type locality for his (1818) Planorbis glabratus as “Charleston, South Carolina.” Pilsbry questioned that locality, but I believe it. We'll come back to this subject in a couple months.

[8] Here are the originals:

- Castelnau, F. (1839) Note sur la Source de la Rivière de Wakulla dans la Floride. Bulletin de la Société de Géographie 11 (2): 242 – 247.

- Castelnau, F. (1842) Vues et Souvenirs de l’Amérique du Nord. Paris.

- Castelnau, F. (1842) Note de deux Itinéraries de Charleston à Tallahassée. Bulletin de la Société de Géographie 18 (2): 241 – 259.

- Castelnau, F. (1843) Essai sur la Floride du Milieu. Nouvelles Annales des Voyages et des Sciences Géographiques 110, 4: 129 – 208.

[9] And here are the translations:

- Castelnau, F., A.R. Seymour and M.F. Boyd (1948) Essay on Middle Florida, 1837 – 1838. The Florida Historical Quarterly 26(3): 199 – 255.

- Seymour, A.R. and F. Castelnau (1948) Comte de Castelnau in Middle Florida, 1837 – 1838. Notes concerning two itineraries from Charleston to Tallahassee. The Florida Historical Quarterly 26(4): 300 -324.

[10] “Here I was able to form an idea of the character of the people of this region, by noticing the ramshackle condition of the ordinary houses, all the windows of which were broken and the doors broken down. I asked the cause of it and I learned that a few days before all of the inhabitants having got drunk and committed this havoc.”

[11] Five of those letters, anyway.