Editor’s Note – This essay was subsequently published as: Dillon, R.T., Jr. (2023b) Somatogyrus and Yankees in North Alabama. Pp 279 – 288 in The Freshwater Gastropods of North America Volume 6, Yankees at The Gap, and Other Essays. FWGNA Project, Charleston, SC.

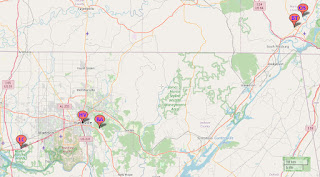

Early in the morning of April 10, 1862, eight thousand

Federal troops under the command of Gen. Ormsby Mitchel captured the sleeping

town of Huntsville, Alabama, without firing a shot [1]. Knowing that both of the main armies were

licking their wounds from the Battle of Shiloh about 120 miles west on the banks

of the Tennessee three days earlier, Mitchel seized the opportunity for a

lightning strike south from Shelbyville.

By the end of April, he controlled 80 miles of the Memphis &

Charleston Railroad from Bridgeport to Decatur, writing to Secretary of the

Army Edwin Stanton, “All of Alabama north of the Tennessee River floats no flag

but that of the Union.” Mitchel’s

Division held North Alabama for four months, withdrawing in reaction to Braxton

Bragg’s thrust north from Chattanooga in August [2]. By September they were home on the banks of

the Ohio in Louisville.

|

| Dr. DeCamp at the Elk River [1] |

Attached to Mitchel’s command was the First Michigan

Engineers and Mechanics Regiment, numbering among its ranks a Grand Rapids

surgeon named Dr. William Henry DeCamp (1825-1898)

[3]. DeCamp had been born in upstate New York and

moved to Grand Rapids in 1854, where he set up a medical practice. He was one of the founders of the “Grand

Rapids Lyceum of Natural History,” and had more than a hobbyist’s interest in

shells. And so it was accomplished that

sometime between April and August of 1862, somewhere in the vicinity of

Huntsville, Alabama, Dr. W. H. DeCamp, Surgeon US Army, stooped to capture a

small detachment of rebel freshwater gastropods.

DeCamp detailed his prisoners back behind the lines to his

friend and fellow member of the Grand Rapids Lyceum, Alfred Osgood Currier

(1817 – 1881), who forwarded a subset onward to Dr. Isaac Lea in Philadelphia

[4]. And if all of this sounds vaguely

familiar to you, your memory is to be commended. For back on [4Aug19] I spun a very similar

yarn about Capt. S. S. Lyon, who arrived at Cumberland Gap this very same

summer of 1862, as uninvited as Dr. DeCamp, and stooped to capture a regiment

of rebel pleurocerids from the ice cold waters of East Tennessee as boldly as

Dr. DeCamp in North Alabama. And Capt.

Lyon sent his prisoners to Dr. Lea as well.

So in my essay of [4Aug19], I wrote, “In May of 1863, a

scant nine months later, Lea described four new species of Goniobasis” sent to

him by Capt. Lyon from Gap Springs [5].

Actually, to be quite precise, Lea published brief, Latinate

descriptions of 15ish [6] species in that Mayish [7] paper, including six

captured by “Capt. S. S. Lyon, U.S. Army,” six captured by “Dr. Wm. H. DeCamp

M.D., Surgeon US Army,” and three arrested by civilians working well behind the

lines. The six DeCamp species included

three pleurocerids from the Falls of the Ohio in Louisville, two pleurocerids

from North Alabama, and Amnicola currieriana, from “Huntsville.” Lea’s currieriana was the first specific

nomen unambiguously ascribed to what we today recognize as the hydrobioid genus

Somatogyrus in the drainages of The Tennessee.

Lea published a more complete description of A. currieriana

in 1866, together with a figure [8].

“This little species differs from all other Amnicolae which I have seen

in the broad deposit of the columella, particularly in the middle, where it

covers the umbilicus.” And indeed the

1:1 figure on Lea’s Plate 24 does show a very robust, solid little shell, no

umbilicus in evidence. Compare the

grayscale figure at lower right below to typical shells from five other

Somatogyrus populations more recently sampled from North Alabama. We’ll have more to say about those five

modern populations next month.

|

| 1.5 x life size. |

It never ceases to amaze me how the War for Southern

Independence prompted such a blossoming of interest in little-brown crap snails

throughout Yankeedom 1861 – 1865. Every

gentleman of means north of the Mason-Dixon line became a Malacologist, a

Quaker, or both

[9]. In September of 1862,

just 8 – 10 months prior to Isaac Lea’s description of

A. currieriana, his

younger colleague George W. Tryon had published a description of a very similar

Amnicola depressa from the Mississippi River at Davenport

[10]. And in February of 1863, three or maybe five

months prior, Theodore Gill (also of Philadelphia) had selected George Tryon’s

depressus, as the type of his new genus

Somatogyrus [11].

Tryon added two fresh species to the genus in 1865 [12]:

Somatogyrus parvulus from the Powell River (a tributary of the Tennessee above

Knoxville) and S. aureus “received from Mr. Lea several years ago” from

somewhere in the “Tennessee River.” And

we were off to the races. Between 1904

and 1915 Bryant Walker [13] described 22 new species of Somatogyrus [14], and

other authors shoveled on as well, to the point that Burch’s 1982 Bible [15]

listed 35 species of the genus, including 9 nominal species described from

North Alabama alone, all utterly indistinguishable. And alas, no lithoglyphid-Goodrich [16] has subsequently

arisen to clean up the taxonomic mess.

All 35 species were described on the basis of qualitative

differences in shell morphology alone.

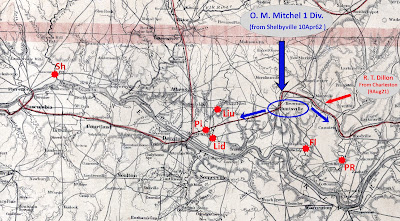

For example, the first species described by Walker in his 1904 paper was

S. hinkleyi from the Coosa River (of the Mobile Basin) at Wetumpka, AL. Walker wrote, “It differs from all the known

species in the elevated spire and conical form excepting S. pennsylvanicus and

virginicus herein described, but those species are much smaller and decidedly

different in contour.” Somatogyrus

hinkleyi is figured (1) and (2) on Walker’s plate below, pennsylvanicus is (15)

and (16), and virginicus is figured (17), (18), and (19). You be the judge.

|

| From Walker (1904) |

But let me back up and edit my opinion that all 35 nominal

species of Somatogyrus are “utterly indistinguishable” just slightly [18]. One of the 11 species of Somatogyrus that

Walker described in 1904, S. umbilicatus was different looking. Collected from the Coosa River at Wetumpka,

S. umbilicus was so lightly shelled that it had an umbilicus, as its name

telegraphs so plainly. My readership of

long memory and narrow interest may remember that Bryant Walker went on to

propose a new genus, Clappia, to hold his nomen umbilicatus in 1909 [19].

And might some of you also remember that in 2012 I reported

discovering two populations of Clappia in East Tennessee – one in the

Sequatchie River, and the other way up in the headwaters of the Powell in SW

Virginia [19]? You can be forgiven if

your memory fails you now. But hold

those tidbits about Clappia tight till next month. You’re going to need them.

I suppose I might also expand my observation above that no

lithoglyphid-Goodrich has risen to clean up the Somatogyrus mess in these

latter days. Fred Thompson did publish a

33-page monograph on the group in 1984 [20], selecting one representative from

each of the five lithoglyphine genera he recognized in North America (Gillia,

Fluminicola, Somatogyrus, Clappia, and Lepyrium) for detailed anatomical

review. But here is a telling quote from

the second paragraph of Thompson’s introduction:

“This study stems from two independent investigations. The first was an attempt to determine

species-group characteristics within Somatogyrus, a genus containing many

species (Burch & Tottenham 1980).

The study was tabled temporarily because very little anatomical

diversity was discovered among the species examined. Independently I examined the anatomy of Lepyrium

showalteri (Lea), a snail previously placed in a monotypic family of uncertain

affinity. Its soft anatomy was found to

be hardly distinguishable from that of Somatogyrus.”

Thompson never picked his first “independent investigation”

back up off the table. Apparently as far

as he could ever tell, all 35 of the nominal Somatogyrus species catalogued in

the Burch Bible were as utterly indistinguishable anatomically as they were

shell morphologically. In fact, the only

soft-part difference of any sort he reported across all five lithoglyphine

genera was the presence of a papilla on the penis of Gillia and

Fluminicola. Even the penial morphology

of Somatogyrus, Clappia, and Lepyrium is indistinguishable, even by the most

discerning splitter – just a simple, pointy hose.

Had Thompson understood the hydrobiids as Goodrich

understood the pleurocerids, at this point he would have synonymized the entire

35-member crap-pot of Somatogyrus down an order of magnitude to three species

and a subspecies. Instead, he added an

appendix of his 1984 paper for the description of yet another utterly

indistinguishable species of Somatogyrus from Georgia, S. rheophilus. Fred Thompson was no Calvin Goodrich. And it is through the dusky twilight of

Walker and Burch that we still walk to this day.

|

| From Fig 43 of Thompson [20] |

One might imagine, from all the taxonomic excitement

generated by Bryant Walker, his forebears, contemporaries and successors, that

populations of

Somatogyrus must have been common throughout the Tennessee River

basin in the early 20th century. That is

certainly not true today, and I’m not sure it was true even back then. Pilsbry & Rhoads (1896) reported a

Somatogyrus population in the “Nolachucky River near Greeneville” which I have

not been able to verify

[21]. Nor can I

confirm the populations that Walker (1904) reported in the Tennessee River at

Knoxville, or in its tributary the Holston.

But here is an important point. The five major tributaries of the Tennessee

River above Knoxville, from north to south, are the Powell, the Clinch, the

Holston, the Nolichucky, and the French Broad.

Tryon described his (1865) S. parvulus from the Powell, where

populations still hang on today. Two

generations later, Pilsbry & Rhoads (1896) and Walker (1904) identified

populations collected from the Holston 20 miles south of the Powell and the

Nolichucky 20 miles south of the Holston as Somatogyrus aureus. Between Tryon and Pilsbry came the immortal

team of Dr. James Lewis and Miss Annie E. Law.

Dr. James Lewis (1822 – 1881) was a dentist/conchologist

from Mohawk, NY, who was reputed to have one of the greatest private

collections of American land and freshwater shells in existence at the time of

his death. According to his obituary in

The American Naturalist [22], he “arranged and classified many public

collections, among which were the American fresh-water shells in the

Smithsonian Institution, the last critical revision of which was made by him.” Really?

He should be better known today than he is.

Miss Annie Elizabeth Law (1842 – 1889), school teacher and

alleged Civil War spy [23], was born in England but spent most of her life in

the vicinity of Maryville, Tennessee [24].

“Through Col. W. G. McAdoo, of Knoxville, she was introduced to Dr.

James Lewis, of Mohawk, New York, who wished her to collect shells. She had from childhood a taste for shells,

mineralogy, entomology, botany, in fact everything connected with nature,” and

so was apparently eager to comply. Over

a period of some two years, Miss Law walked 20 miles of the Holston River “from

Little River Shoals to Chota Shoals,” collecting both the bivalves and the

gastropods she discovered along the way, posting them to her sponsor in Mohawk,

NY. In his 1871 report of her expedition

[25], Lewis observed:

“I have from Miss Law numerous shells identical with

Somatogyrus parvulus, Tryon, found, at very low stages of water, in little

pools left by the receding water along swift, shallow, gravelly portions of the

Holston. Less abundantly a somewhat

larger shell agreeing with S. aureus Tryon.

Also larger shells identical with “Amnicola Currieriana, Lea,” found in

still water, along muddy portions of the Holston, near the shore. They are, without doubt different ages of one

species. Mr. Leas name for the species

takes precedence.”

Yes, Dr. James Lewis identified Somatogyrus currierianus

(Lea 1863) in East Tennessee. And he

synonymized both parvulus (Tryon 1865) and aureus (Tryon 1865) underneath it.

That brings our essay full circle, back to the exciting

summer of 1862, and Dr. W. H. DeCamp standing on the banks of the big-river

Tennessee somewhere in the vicinity of Huntsville. The key to understanding the Somatogyrus of the

entire Tennessee River drainage is to understand Somatogyrus currierianus in

North Alabama. Next time, a fresh adventure!

Notes

[1] I have taken most of the historical narrative in the

first two paragraphs above, as well as the interesting figure, were from:

- Hoffman, M. (2007) My Brave Mechanics: The First Michigan

Engineers and their Civil War. Wayne

State University Press, 470 pp.

[2] Mitchel was promoted to command the entire Department of

The South, and transferred to Beaufort, SC, where he died almost immediately of

Yellow Fever. Why was Mitchel in

Beaufort? See:

- The Many Invasions of Hilton Head [16Dec15].

[3] This is the fourth time that the name of Dr. W. H.

DeCamp has come up in the 25 year record of this blog. We focused a great deal of attention on

Goniobasis decampii Lea 1863/66 [6] in “A House Divided” [10May20], and on

Campeloma decampi (Binney 1865) in “Fun With Campeloma” [7May21]. Lymnaea decampi Streng 1906 also garnered a

brief mention in footnote [3] of “Malacological Mysteries I: The type locality

of Lymnaea humilis” way back in [25June08].

[4] For a brief biography of the “Nestor of American

Naturalists” see:

- Isaac Lea Drives Me Nuts [5Nov19]

[5] Lea, Isaac (1863) Descriptions of fourteen new species

of Melanidae and one Paludina.

Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 15: 154 –

156.

[6] Lea apparently intended to include a description of

Melania decampii from Huntsville in his paper of Mayish [7] 1863, but that

paragraph was omitted. In his follow-up

paper of 1866 [8] he stated that the Latinate description of Melania decampii

had been published previously in “Proc. Acad. Nat. Sci., 1863, p. 154” but it

was not. Was Lea’s statement an overt

fabrication, or just sloppiness? Either

way, stuff like this drives me nuts.

Absolutely nuts [4].

[7] Lea apparently read his paper in May of 1863, and “May”

is printed on the bottom of the published pages, but the front of the published

volume says, “June and July, 1863.”

[8] Lea, Isaac (1866)

New Unionidae, Melanidae, etc. chiefly of the United States. Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of

Philadelphia (New Series) 6: 113 – 187.

[9] For more about the malacologists of Yankeedom 1861 –

1865, see:

- Ferrissia fragilis (Tryon 1863) [6Feb19]

[10] Tryon, G. W. (1862)

Notes on American fresh water shells, with descriptions of two new

species. Proceedings of the Academy of

Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 14: 451 – 452. I really think that the Mississippi River Somatogyrus populations are best identified today as Somatogyrus integra (Say 1829).

[11] Gill, T. (1863) Systematic arrangement of the mollusks

of the family Viviparidae, and others, inhabiting the United States.

Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 15: 33 – 40.

[12] Tryon, G. W. Jr. (1865) Descriptions of new species of Amnicola,

Pomatiopsis, Somatogyrus, Gabbia, Hydrobia and Rissoa. American Journal of Conchology 1: 219-222, pl

22, figs 5-13.

[13] Here’s a brief biography of Michigan’s Father of

Malacology:

- Bryant Walker’s Sense of Fairness [9Nov12]

[14] Bryant Walker’s

papers on Somatogyrus:

- Walker, B. (1904) New

species of Somatogyrus. Nautilus 17: 133

- 142.

- Walker. B. (1906) New

and little known species of Amnicolidae.

Nautilus 19: 97-100, 114-117.

- Walker, B. (1909) New

Amnicolidae from Alabama. Nautilus 22:

85 - 90.

- Walker, B. (1915) Apical characters in Somatogyrus with

descriptions of three new species. The

Nautilus 29: 37 - 41, 49 - 53.

[15] This is a difficult work to cite. J.B. Burch’s North

American Freshwater Snails was published in three different ways. It was initially commissioned as an

identification manual by the US EPA and published by the agency in 1982. It was also serially published in the journal

Walkerana (1980, 1982, 1988) and finally as a stand-alone volume in 1989

(Malacological Publications, Hamburg, MI).

[16] A “lithoglyphid” is a member of the modern family

Lithoglyphidae, previously a subfamily of the Hydrobiidae [17], bearing

featureless anatomy and shell morphology, characterized by nothing

whatsoever. And Calvin Goodrich was the

twentieth-century hero who brought science to the classification of the

Pleuroceridae, which was an order of magnitude worse. For more, see:

- The Legacy of Calvin Goodrich [23Jan07]

[17] Wilke, Haase, Hershler, Liu, Misof, and Ponder (2013)

Pushing short DNA fragments to the limit: Phylogenetic relationships of

“hydrobioid” gastropods. Molec. Phyl.

Evol. 66: 715 – 736. For a review, see:

- The Classification of the Hydrobioids [18Aug16]

[18] Well, to be fair, Walker described two species of

Somatogyrus with distinctive shell morphology: umbilicatus in 1904 and

biangulatus in 1906. The latter seems to

have been endemic to the main Tennessee River at Muscle Shoals, and now (I

fear) extinct.

[19] See my 2012 series of essays for a study of Bryant

Walker, Somatogyrus, Clappia, and the relationships between all three:

- Bryant Walker’s Sense of Fairness [9Nov12]

- On Getting Clappia in Tennessee [3Dec12]

[20] Thompson, F.G. (1984) North American freshwater snail

genera of the hydrobiid family Lithoglyphinae.

Malacologia 25: 109 – 141.

[21] Pilsbry, H. & Rhoads, S. (1896) Contributions to the Zoology of Tennessee,

Number 4, Mollusca. Proc. Acad. Nat. Sci. Phila. 1896: 487-506.

[22] Call, R.E. (1881) Memoriam of Dr. James Lewis. The American Naturalist 15: 506-508.

[23] I have not been able to confirm the allegations of

spying, and I strongly suspect it was for the Union, but I don’t care, I would

have really loved to meet Miss Annie E. Law.

Hell, if I was 120 years younger, I would have proposed.

[24] I have pieced my biographical background on Miss Law

from a variety of secondary sources, including Tucker Abbott’s (1973) American

Malacologists, The Poppe’s conchology.be website, and Nautilus 40: 132 – 133.

[25] Lewis, J. (1871)

On the shells of the Holston River.

American Journal of Conchology 6: 216-226.