Editor’s Note – This essay was subsequently published as: Dillon, R.T., Jr. (2023b) My Buddy, Bob. Pp 203 – 210 in The Freshwater Gastropods of North America Volume 6, Yankees at The Gap, and Other Essays. FWGNA Project, Charleston, SC.

Although we studied at different institutions, Bob Hershler was my best friend in graduate school. He was enrolled at Johns Hopkins way down in Baltimore, and I at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. But we shared George Davis as our major advisor, so for several years we both spent most of our hours many of our days in the Malacology Department at the Academy of Natural Sciences.

In many ways, Bob was closer to George than I was, ultimately completing his dissertation on a morphological study of an endemic radiation of hydrobioids in northern Mexico [1], really rather similar to George’s masterpiece in southeast Asia [2]. Meanwhile, I was in the lab running allozyme gels on the opposite of an endemic radiation in the American pleurocerids [3].

|

| Rob & Bob in Philadelphia, 1977 |

Bob often slept on the carpet under the big table in the malacology library. And there was a night watchman, stationed at the desk at a side door downstairs, who patrolled regular rounds inside the building. The watchman knew Bob was sleeping under there, which he most certainly was not supposed to be doing, but nevertheless turned a blind eye.

One evening Bob was running a set of exploratory electrophoresis gels, and after he got his samples on, decided to go out for supper. And he walked by the watchman at the side door and out onto 19th Street and was gone for perhaps an hour or so. And when he returned to the 19th Street door, the watchman was on his rounds. And the door was locked.

And Bob panicked. Fearing that his gels would cook and might ultimately (I suppose?) start a fire, he pulled the fire alarm on the side of the building. I will leave to your imagination what response might follow a fire alarm at a 150-year-old building crammed with rotten alcohol and animal skins in downtown Philadelphia in the middle of the night.

Bob was awarded his Ph.D. in 1983, the same year that I was awarded mine, and by the blessing of divine providence, was able to win a curatorial position at the U.S. National Museum a couple years later. Such plums are few and far between for scientists with our very specialized (and quite possibly obsolete) backgrounds. My self-effacing buddy Bob confided to me shortly thereafter, “It was a weak field” [4].

But at the USNM Smithsonian, Bob’s career flourished. His research focused almost entirely on the hydrobioids, of which he became the unchallenged North American authority, publishing over 100 peer-reviewed papers, many monographic in their size and scope. His malacology was neoclassical, featuring lovely, detailed drawings of the dissected animals themselves, in the style of a Henry Pilsbry or our shared mentor George. But he often whistled modern notes. At his best, Bob was able to recognize intrapopulation and interpopulation variation along with the most evolutionary of his contemporaries. His unification of Pyrgulopsis robusta, for example, will have a lasting impact [6].

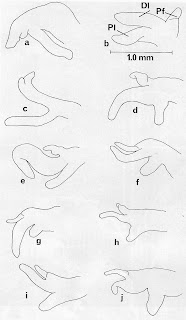

The 1990 monograph of the phreatic genus Fontigens he published with John Holsinger and Leslie Hubricht [7] was a thing of beauty. It opens with a marvelous and detailed examination of morphological variation in the most common species, Fontigens nickliniana, depicting shells of all shapes and penial complexes of in all their elaborate forms and twisted wonder. His section subtitled “material examined” lists hundreds of distinct springs and spring runs in ten different states where populations of F. nickliniana can be found, with locality data of sufficient quality so that any subsequent worker can go and look at the things himself, if he has any questions. That’s the best part of the monograph.

|

| F. nickliniana penis variation [8] |

Then moving forward from a rock-solid understanding of morphological variation in Fontigens nickliniana, Bob proceeded by rigorous methodology to distinguish nine additional species in the genus. Four of these are more or less sympatric with nickliniana in the Valley-and-Ridge Province of Virginia, most strikingly F. orolibas, which even co-occurs mixed with F. nickliniana, lending credence to the hypothesis of reproductive isolation. Again, Bob offers lovely figures of shell, radula, and reproductive anatomy for each, with excellent locality data. And he iced the cake with a dichotomous key to cleanly distinguish among the ten total. This work is easily on par with that of a Hubendick or a Meier-Brook [9]. Bob’s 1990 Fontigens monograph is as good as classical malacology ever got or can get.

Almost as good, equally important, and even larger was his 1994 monograph on the North American Pyrgulopsis [10]. I keep a copy by my desk and refer to it often. In this 115-page tour-de-force Bob recognized 11 Pyrgulopsis species from Eastern North America as well as the 54 that (by that early date) had been described from the American West. Of the 54, Hershler had himself described 21. We will have much more to say about both the Eastern subset (now referred to Marstonia) and the western subset (still Pyrgulopsis) in coming months.

I think it is fair to say, by a margin of approximately 54 to 11, that Bob’s greatest love was his first love – the hydrobioid fauna of the American West. Running my finger through the “Annotated Checklist of Freshwater Truncatelloidean Gastropods of the Western United States” he published with Hsiu-Ping Liu in 2017 [11], I count 43 papers with Hershler as the senior author, including such major contributions as the (63 pg) review of the Arizona hydrobiids he published in 1988, his (140 pg) Cochliopine monograph of 1992, his second (132 pg) Pyrgulopsis monograph of 1998, his (41 pg) Fluminicola monograph of 1996, and his (53 pg) Tryonia monograph of 2001 [12].

From his hypotheses regarding evolutionary relationships among western hydrobioid populations he developed a secondary interest in biogeography, publishing reconstructions of ancient drainage systems [13]. He had little interest in population biology, ecology, or the broader malacofauna beyond the hydrobioids, however. When I approached him about collaborating on the FWGNA project back in 1998, he replied, “I don’t do checklists” [14].

It should not surprise you, after having read the anecdote with which this essay opened, that Bob did not run any sort of genetic laboratory. But in 1999 he developed a tremendously productive relationship with someone who did, Dr. Hsiu-Ping Liu, and for 20 years they made beautiful malacological music together. Of the 43 papers on the western hydrobioids I counted above, 30 were published after 1998, and of those 30, Hsiu-Ping is also listed as an author on 26. In addition, the Literature Cited section of the Hershler & Liu catalog also includes 10 papers with Hsiu-Ping as lead author, Bob’s name following.

|

| Pyrgulopsis penis from Hershler [15] |

[1] Hershler, R. (1985) Systematic revision of the Hydrobiidae (Gastropoda: Rissoacea) of the Cuatro Cienegas Basin, Coahuila, Mexico. Malacologia 26: 31 – 123.

[2] Davis, G. M. (1979) The origin and evolution of the Gastropod family Pomatiopsidae, with emphasis on the Mekong River Triculinae. Monograph of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 20: 1 – 120.

[3] Dillon, R.T., Jr. (1984) Geographic distance, environmental difference, and divergence between isolated populations. Systematic Zoology 33:69-82. [pdf]

[4] I didn’t apply for the 1986 Smithsonian opening. I had accepted an assistant professorship at The College of Charleston in 1983, which was a mighty quick turnaround, but that wouldn’t have stopped me. Curatorships at the USNM are very, very sweet plums [5]. What did stop me from applying for the position at the Smithsonian that Bob Hershler ultimately won in 1986 might be grist for a future post on the FWGNA blog.

[5] I happened to notice on a website called federalpay.org that at his retirement, Bob was earning a base salary of $161,900. That is way more than twice what I ever made, in 33 years of labor at a mid-sized college of regional reputation, grading thousands of lab reports written by entitled 19-year-old sorority girls.

[6] Hershler, R. & H-P. Liu (2004) Taxonomic reappraisal of species assigned to the North American freshwater gastropod subgenus Natricola (Rissooidea: Hydrobidae). The Veliger 47: 66-81. Hershler, R. & H-P. Liu (2000) A molecular phylogeny of aquatic gastropods provides a new perspective on biogeographic history of the Snake River region. Molec. Phyl. Evol. 32: 927-937. For a review of the tempest these two papers stirred up in the teacup of freshwater gastropod conservation, see:

- Idaho springsnail showdown [28Apr05]

- Idaho springsnail panel report [23Dec05]

- When pigs fly in Idaho [30Jan06]

[7] Hershler, R., J.R. Holsinger & L. Hubricht (1990) A revision of the North American freshwater snail genus Fontigens (Prosobranchia: Hydrobiidae). Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology 509: 1-49. For an appreciation, see:

- Springsnails of The Blue Ridge [26July06]

[8] This is a scan of Figure 7 from Hershler, Holsinger & Hubricht [7]. It shows camera lucida outline drawings of penes from ten different populations of F. nickliniana, collected mostly from Virginia. Pl = proximal penial lobe, Dl = distal penial lobe, Pf = Penial filament.

[9] For appreciations of the work of those two icons of neoclassical malacology, see:

- The classification of the Lymnaeidae [28Dec06]

- Character phase disequilibrium in the Gyraulus of Europe [4Feb22]

[10] Hershler, R. (1994) A review of the North American freshwater snail genus Pyrgulopsis (Hydrobiidae). Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology 554: 1-115. I mentioned idly “leafing through” this important work back in 2016, for example:

- Marstonia letsoni, quite literally obscure [5Feb16]

[11] Hershler & Liu (2017) Annotated Checklist of Freshwater Truncatelloidean Gastropods of the Western United States, with an Illustrated Key to the Genera. US Bureau of Land Management Technical Note 449: 1 – 142.

[12] Hershler, R. 1998. A systematic review of the hydrobiid snails (Gastropoda: Rissooidea) of the Great Basin, western United States. Part I. Genus Pyrgulopsis. Veliger 41:1-132. Hershler, R. 2001. Systematics of the North and Central American aquatic snail genus Tryonia (Rissooidea: Hydrobiidae). Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology 612:1-53. Hershler, R., Frest, T.J. 1996. A review of the North American freshwater snail genus Fluminicola (Hydrobiidae). Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology 583:1-41. Hershler, R., Landye, J.J. 1988. Arizona Hydrobiidae. Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology 459:1-63. Hershler, R., Thompson, F.G. 1992. A review of the aquatic gastropod subfamily Cochliopinae (Prosobranchia: Hydrobiidae). Malacological Review Supplement 5:1-140.

[13] Hershler, R., D.B. Madsen, and D.R. Currey (eds) Great Basin Aquatic Systems History. Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences 33: 1 – 405 (2002).

[14] Ironic in light of the title of his 2017 publication, cited at note [11] above.

[15] This is a detail from Figure 2 of Hershler [10]. It depicts three views of a whole mount penis dissected from Pyrgulopsis californiensis. Tg = terminal gland, Pg = penial gland, Vd = ventral gland, Dg = dorsal glands.

[16] I was banned from campus and forced into retirement for a Woodrow Wilson quote four weeks into the spring semester of 2016. A press release issued by the Provost’s Office at the College of Charleston on the afternoon of February 21 stated, in part, “We have endured that sanctimonious asshole for 33 years, 5 months, 21 days, 13 hours and 15 minutes, and cannot stand him for one second more.” For a review, see:

- Inside Higher Education [8Aug16]

I used my settlement from the lawsuit to set up the FWGNA as

a sole proprietorship.