Editor’s Note – This essay was subsequently published as: Dillon, R.T., Jr. (2023b) Malacological mysteries: Is Marstonia olivacea extinct? Pp 269 – 278 in The Freshwater Gastropods of North America Volume 6, Yankees at The Gap, and Other Essays. FWGNA Project, Charleston, SC.

Questions regarding the habitat and range of the hydrobiid snail known today as Marstonia olivacea have always taken precedence over any other aspect of its biology. Originally described in the genus Amnicola by Henry Pilsbry in the February 1895 issue of The Nautilus [1], the name had already appeared in that journal twice previously – first in March of 1894 [2], then again in December [3].

Both anticipatory articles were contributed by Prof. H.E. Sargent of Woodville, AL, and both focused on habitat. In the March article, “Shell collecting in Northern Alabama,” Professor Sargent observed:

“Huntsville, Alabama, is a somewhat exceptional southern city in that it has an abundant supply of pure spring water bursting forth from its very foundations. This spring of sparkling lime water, beside supplying the city mains, affords a constant stream several feet in width with several inches in depth go to waste. […] The upper surfaces of the rocks were found to be covered with a species of Amnicola which the Editor … proposes the name of Amnicola olivacea Pils.”

And in a little “Notes and News” item tacked onto the end of the December 1894 issue of The Nautilus, the good professor added,

“AMNICOLA OLIVACEA PILS. – In April, I visited the original locality (Huntsville, Ala.) and was surprised to find this species in vast numbers. The stream has a mud bottom which is much indented with cow tracks. In these the Amnicola had congregated – not as a layer on the surface, but as a solid mass. […] The stream receives some of the city sewerage, so it is probably a good feeding-ground.”

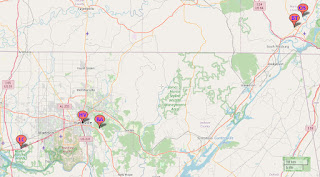

Prof. Sargent’s December remark about “sewerage” in Huntsville’s Big Spring Creek is telling. We ourselves first visited that unfortunate little body of water in our essay of [15Apr20], questing for Isaac Lea’s Melania perstriata, and gave it another nod in last month’s essay [15Aug23], searching for the illusive Somatogyrus currierianus. The last time I visited that “marvel to Indian and frontiersmen alike,” I couldn’t even find a Physa. I have nevertheless marked the Huntsville Big Spring as HV on the map below.

But returning to the thread of our story. Henry Pilsbry did not apparently find space to wedge his formal description of Amnicola olivacea until the fifth article of the issue he published in February 1895. And when it appeared it was maddeningly brief and spare, unfigured, and absent any anatomical observations whatsoever [4]. The two shells that he measured were unusually large by hydrobiid standards, however, both “Alt 4.2 mm,” and slender “being of more elongated contour than any other Northern forms except Amnicola lustrica.” Those observations plus the type locality (“Huntsville, Ala., collected by Prof. H. E. Sargent”) were sufficient to allow subsequent authors to establish the identity of Pilsbry’s taxon.

The first among those subsequent authors seems to have been my hero Calvin Goodrich [5], who wrote in 1944, “This species is somewhat common in streams and springs in and around Huntsville, Madison County, Alabama, drained by the Tennessee River. Specimens taken by Smith in the Coosa, Minnesota Bend, Etowah County, Alabama [6], have been identified as olivacea.” This strongly implies that Goodrich was aware of populations of Pilsbry’s A. olivacea at other localities beyond Huntsville’s Big Spring. The four lots of Marstonia olivacea held in the UMMZ collection today, however, all give locality as either “Huntsville” or “Huntsville Spring” [7].

|

| M. olivacea [12]: lectotype, Hershler, UF279638 |

But Goodrich was a pleurocerid guy, not a hydrobiid guy. It was Fred Thompson who first stepped forward to examine Pilsbry’s Amnicola olivacea with a critical eye, in his landmark monograph of 1977 [8]. As my longsuffering readership will remember from last fall [4Oct22], it was Thompson who first elevated F. C. Baker’s [9] nomen Marstonia to the level of a full genus, recognizing as he did eight species in it: Pilsbry’s well-known lustrica, Pilsbry’s obscure olivacea, and six species of his own.

Thompson wrote, “Apparently this species (M. olivacea) was confined to Big Spring Creek in the historic heart of Huntsville.” And he continued, “This snail is probably extinct. The creek is badly polluted and has been channelized for most of its course. No specimens were found by the author during two visits to Big Spring Creek during 1973.” He went on to examine the paratype lot (N = 456 specimens!) in the ANSP, valiantly attempting “to extract and relax dried bodies,” failing. He selected the shell figured above as a lectotype. And regarding its morphology, Thompson observed, “If M. olivacea was from a more northern locality, I would be tempted to consider it a synonym of the highly variable M. lustrica.” He concluded, “This species’ status remains uncertain.”

My longsuffering readership will also remember from last fall [4Oct22] that Marstonia was briefly synonymized under the genus Pyrgulopsis in 1987 by the dynamic duo of Hershler and Thompson, only to be resurrected again in 2002 [10]. In the interim was published Bob Hershler’s masterful 1994 monograph [11] treating Pilsbry’s olivacea as an “Eastern American Species” in the (temporarily very large) genus Pyrgulopsis.

My Buddy Bob’s scanning electron micrograph of the shell of a young “Pyrgulopsis” olivacea [12] is reproduced middle above. Bob was also apparently able to rehydrate soft tissues from inside some of Pilsbry’s dried shells, contributing a figure of the radula and a four-line description of the penial morphology. Hershler left the penis unfigured, alas, and only compared it to other species in broad outline [13]. He concluded, briefly, “This snail resembles widely disjunct P. lustrica in shape of shell and penis, but differs in having strong spiral lines on the teleoconch.”

Hershler quoted Thompson’s understanding of the distribution of P. olivacea, minus any qualification whatsoever, “Known only from type locality, where it is now extinct.” And that would seem to be the end of this month’s lesson. Perhaps class will be dismissed early today? No such luck.

The Florida Museum of Natural History in Gainesville is a marvelous facility, home to a large and well-curated collection extending well beyond regional importance. The review I posted on [22May19] ranked the FLMNH as #5 in the nation by its freshwater gastropod holdings. I’d like to call it a beacon on a hill, a guidepost toward which other states and state universities might sail. But alas, the tide has turned, and the winds have blown ill for a hundred years. We malacologists of these latter days must give thanks for the few scattered beacons we have, as we strain to navigate by their flickering lights.

So it was that on Monday morning, 10Jan22 I found myself sitting at a metal table in the FLMNH collections, running my fingers through Fred Thompson’s hydrobioid collections from North Alabama, pondering weak and weary, over many a quaint and curious lot of freshwater gastropods. And my eye happened to fall on lot UF279638, collected by FGT from “Madison Co: Huntsville Blue Springs” (site BA) on 17Aug2000 [14]. That lot of dry shells, indistinguishable to my eye from common Marstonia lustrica, collected from a large spring on private property 5 miles East of Huntsville, had been identified by Fred Thompson himself as Marstonia olivacea. Marstonia olivacea is not extinct.

And that was not the last, nor the greatest revelation of the morning. The FLMNH collection also held, upon further inspection, a lot UF279620, collected by FGT from Limestone Creek, about 20 miles west of Huntsville, on 16Aug2000, the previous day. See map point LC above [15]. That lot, comprising a couple dozen specimens in 75% ethanol, was curated into the collection as “Pyrgulopsis n. sp.” They were absolutely indistinguishable from lot UF279638.

|

| UF279620, from Site LC |

If Marstonia olivacea ranges 5 miles East of Huntsville, and 20 miles West of Huntsville, might it also range 60 miles East of Huntsville? Begging the indulgence of my readership, allow me to step back 46 years, and eight paragraphs, and get a fresh start into this entire story.

Fred Thompson recognized eight species in his newly elevated genus Marstonia in 1977: lustrica, olivacea, agarhecta (which he himself had described in 1969) and five brand new ones. On page 123 of his monograph, he opined that M. olivacea was endemic to Huntsville and probably extinct. But two pages earlier he had newly described Marstonia ogmorhaphe [16] from Owen Springs, just over the Tennessee line 60 miles NE of Huntsville (map OS). It was initially “known only from its type locality,” but a second population of M. ogmorhaphe was subsequently discovered 5 miles west, in the Blue Spring [17] of Marion County (map BT).

Thompson made no effort to distinguish his new M. ogmorhaphe from the older M. olivacea. Quoting him verbatim from page 120, “Marstonia ogmorhaphe is distinguished from all other species of Marstonia by (1) its large size (4 – 5 mm), and (2) its large number of whorls (5.2 – 5.8).” On page 123, Thompson went on to give the length of the holotype of M. olivacea as 4.35 mm, and number of whorls as 5.4.

|

| Owen Springs, courtesy of Alan Cressler |

Seventeen years later came Bob Hershler’s big Pyrgulopsis monograph [11], and the formal listing of Pyrgulopsis (= Marstonia) ogmorhaphe as “endangered” by the US Fish and Wildlife Service [18]. My buddy Bob’s treatment of this suddenly noble gastropod, now styled the “Royal Snail,” was brief. Both he and Thompson noted the similarity between olivacea and lustrica, and both he and Thompson noted the similarity between ogmorhaphe and lustrica, but neither he nor Thompson thought to compare olivacea to ogmorhaphe.

So, in summary. My biological intuition suggests to me that Marstonia ogmorhaphe (Thompson 1977) is a junior synonym of Marstonia olivacea (Pilsbry 1895). The dispersal capabilities of freshwater gastropods are much greater, and their specific ranges much wider than they are commonly given credit for, even among professionals. The (effectively indistinguishable) Marstonia lustrica ranges across 12 states and 3 Canadian provinces and must have spread across most of this vast territory since the Pleistocene [19]. I cannot see why populations of a second very similar species, best identified as Marstonia olivacea, could not spread 60 miles from North Alabama to East Tennessee. And I cannot find a single speck of evidence suggesting that any reproductive isolation may have evolved subsequently.

Notes

[1] Pilsbry, H.A. (1895) New American fresh-water mollusks. Nautilus 8: 114 – 116.

[2] Sargent, H.E. (1894) Shell collecting in Northern Alabama. Nautilus 7: 121 – 122.

[3] Sargent, H.E. (1894) Amnicola olivacea Pils. Nautilus 8: 95 – 96.

[4] My faithful readership will be familiar with the eccentricities of the character of The Ancient Emperor, Dr. Henry A. Pilsbry. In his capacities as Curator of Mollusks at The Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia and Editor of The Nautilus, he cast a giant shadow across the face of American malacology for 70 years. You are also aware that Pilsbry was simultaneously fastidious and sloppy, capable of precise, detailed, and critical observations of parrot feathers in a pirate attack. For more, see:

- The Emperor Speaks [5Dec20]

- The Emperor, the Non-child, and the Not-short-duct [9Feb21]

- Dr. Henry A. Pilsbry was a Jackass [26Jan21].

[5] Goodrich, C. (1944) Certain operculates of the Coosa River. Nautilus 58: 1 – 10.

[6] The “specimens taken by Smith in the Coosa” were described as Marstonia hershleri by

- Thompson, F. G. (1995) A new freshwater snail from the Coosa River, Alabama (Gastropoda: Prosobranchia: Hydrobiidae). Proc. Biol. Soc. Washington 108: 502 – 507.

[7] All of these lots are undated, alas. They are catalogue numbers 120720 of H.E. Sargent, 143685 of H.H. Smith, 237147 of P.L. Marsh, and 1516 of an unknown collector.

[8] Thompson, F.G. (1977) The hydrobiid snail genus Marstonia. Bulletin of the Florida State Museum 21(3):113-158.

[9] Baker, F. C. (1926) Nomenclatural notes on American fresh water Mollusca. Transactions of the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts, and Letters 22:193-205.

[10] Thompson, F. G. & R. Hershler (2002) Two genera of North American freshwater snails: Marstonia Baker, 1926, resurrected to generic status, and Floridobia, new genus (Prosobranchia: Hydrobiidae: Nymphophilinae). The Veliger 45: 269 - 271.

[11] Hershler, R. (1994) A review of the North American freshwater snail genus Pyrgulopsis (Hydrobiidae). Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology 554: 1 - 115.

[12] The standard lengths of these three figured shells are 4.3 mm for Thompson’s [8] lectotype, 4.5 mm for my selection from lot UF279638, and just 3.4 mm for Hershler’s [11] youngish specimen. My Buddy Bob had a longtime romance with scanning electron microscopy, and tended to select smaller shells for his figures, which are easier.

[13] In fairness to Bob Hershler, the morphology of dried and rehydrated soft tissues cannot be compared to anything other than other dried and rehydrated soft tissues. I would have loved to see a comparison of the penial morphology of M. olivacea, M. lustrica and M. ogmorhaphe, but to do so Bob would have had to desiccate a bunch of fresh lustrica or ogmorhaphe to brittle dryness first.

[14] There is an error in the lat/long coordinates for UF279638 as entered into the FLMNH database, which may have contributed to the obscurity of this record. The correct lat/long coordinates for the Blue Spring of Madison County, Alabama, are 34.7080, -86.5123. They are not “31.66361, -85.50667.” Those are the coordinates of the Blue Springs of Barbour County, AL.

[15] This spot is way downstream near the mouth of Limestone Creek, underneath the I-565 spur, at 34.6317, -86.8667.

[16] Thompson spelled his new species “ogmorphaphe” at the heading of his description and “ogmorhapha” in his table of contents, but “ogmorhaphe” enough times otherwise to make the one-pee-final-e spelling stick.

[17] To be very clear. The Blue Spring of Marion County, Tennessee (35.0816, -85.6325) is different from both the Blue Spring of Madison County, Alabama (34.7080, -86.5123) and the Blue Springs of Barbour County, Alabama (31.6636, -85.5067).

[18] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (1994) Endangered and threatened wildlife and plants; Determination of endangered status for the Royal Snail and Anthony’s Riversnail. Federal Register 59: 17994 – 17998. [FR-1994-04-15]

[19] The hypothesis I am offering here is now fair game for testing with a gene tree. But if you are a bright young graduate student looking for thesis ideas, please first read Essay the paper by Tom Coote [20]. Then read this essay, and the essays linked from it:

- Mitochondrial heterogeneity in Marstonia lustrica [3Aug20]

[20] Coote, T. W. (2019) A phylogeny of Marstonia lustrica (Pilsbry 1890) (Gastropoda: Hydrobiidae) across its range. Northeastern Naturalist 26: 672 – 683.