Editor’s Note – This is the second installment in a projected four-part series on Lymnaea (Galba) bulimoides in Oregon. You might want to refresh your memory of last month’s post [13Feb25] before proceeding.

My goodness, the Willamette Valley is wide open – fields and pasturelands stretching to the horizon in all directions. My target, early on the morning of August 2, 2024, was a ditch along the west side of Bellfountain Road 5 miles SW of Corvallis, Oregon, in the “south-east corner of section 18, range 5 west, township 12 south.” That ditch, as best I could figure, was the study site of a British Columbian biologist named Greg R. Foster, over 50 years ago.

The results of Foster’s charming little 1971 mark-recapture study [1], entitled “Winter vagility of the aquatic snail Lymnaea (Galba) bulimoides,” do not concern us here. But by all criteria – its accessibility, its protection, and the biological characterization of the crappy little amphibious lymnaeid population there dwelling, Foster’s study site stands even unto the present day as the best candidate to restrict the type locality of the intermediate host of livestock liver fluke in the Pacific Northwest.

|

| By Bellfountain Road, 2Aug24 |

Foster’s study was conducted over a period of ten weeks from December 26 – March 8, 1969, quite the surprising time window, if you stop to consider it, for so northerly a latitude. He explained this peculiarity in the first paragraph of his discussion, as follows:

“In many aspects concerning life cycle and ecology L. bulimoides is quite similar to the aquatic snail Aplexa hypnorum (L.) found in the Molenpolder at Yerseke, Holland (Den Hartog & De Wolf, 1962). Both are found in shallow ditches on soil of about the same type. Both are extremely tolerant of cold and desiccation. Both have life spans coinciding with the time between the end of the summer drought in one year and the beginning of the drought in the next year.”

I had flagged the Den Hartog paper [2] in the early-1990s, when I was doing research for my book [3], collecting all the diverse pulmonate life cycles into a single synthesis on pp 156 – 162. And I myself had a bit of field experience hunting Aplexa in Michigan, as well as the (ecologically analogous) Physa carolinae in our local swamps right here in the Southeastern coastal plain [4]. And I was quite well aware that Aplexa populations cannot be sampled in the summer. In retrospect, perhaps I should have taken Foster’s analogy as a warning.

Foster’s follow-up paper of 1973 [5], “Soil type and habitat of the aquatic snail Lymnaea (Galba) bulimoides during the dry season,” was even more interesting, and even more revealing of the peculiar biology of the critters I was determined to sample this day. This second study was conducted in July and August of 1969 over a much larger area, “publicly owned ditches, streams and pastures that could be reached with a truck and then by foot” in a large township-and-range block around Corvallis. Foster used a bucket auger to collect 456 soil samples to a depth of 3 inches, carrying each back to the lab and submerging each in water. A total of 60 living L. bulimoides were collected, depending on soil type.

|

| View SW, from Bellfountain Rd. |

I had

prepared myself by inspecting the fields along Bellfountain Road using that

little “Street View” man at the lower right corner of Google Maps, which showed a

soggy fallow field, with significant standing water, and several inches of

water dribbling through the roadside ditch.

That was the last time the Googlemobile had passed that way, in April of

2024.

The

situation that greeted my eye on the morning of August 2, 2024, however, was

Not That. If I have ever seen a soil so

dry and hard as the bottom of that ditch, or smelled grass so brown and

brittle, or felt a wind so arid as that which stung my cheek that morning,

standing on the verge of that road from nowhere to nowhere in the middle of

flat nothing Oregon, I cannot remember it.

Ah, but

there were dead shells in that ditch, L. bulimoides sure enough, in some places

quite a lot of them. And I jumped the

ditch and stomped through the hayfield, very much as I had at the Gahr Farm the

previous afternoon, and additional shell remains were not uncommon. And at one point I even stumbled upon a

little pile of Helisoma trivolvis shells, frozen in death, confirming that the

water levels here had at some day in the recent past been significant. But today was not that day.

|

| The Oregon Snail Team! [6] |

And I had a late-morning appointment to keep with my buddy Bill Gerth at the OSU Department of Fisheries, Wildlife and Conservation. I trust my readership will remember Bill from his introduction last month, yes? I was pleased to meet Courtney Hendrickson in Bill’s lab as well, along with parasitologist Mike Kent. Courtney gifted me that small sample of N = 2 L. bulimoides she had collected at Gahr Pond in May of 2023, for which I will remain eternally grateful. Bill offered a suggestion on a locality where I should be able to find water, even at this date so advanced in the summer, a creek just east of the little city of Halsey, about 15 miles south of Corvallis. And he pointed me to the local Fred Meyer Department Store, where I was able to purchase a shovel and a 5-gallon bucket.

And I

was off again. Halsey (pop 904), founded

on the Oregon & California railway in 1872, was at one time famous for the

iconic Cross Brothers Seed and Grain warehouse, towering 152 feet above the

flat ryegrass fields of western Linn County [7]. And it was only there, well into the third

day of my Oregon Expedition, that the true enormity of the challenge before me

was finally laid bare.

My

spirits leapt upon arrival at Spoon Creek, 2 km east of town, as pretty an

agricultural ditch as I can ever remember stomping down into (A). The water was surprisingly clear and cool;

the habitat surprisingly rich and diverse.

Physa acuta, Helisoma trivolvis, and Gyraulus parvus were all

common. And without any difficulty I was

able to survey extensive mud banks of the sort where, in The East, crappy

little amphibious lymnaeids would have been jumping into my sample vials. But alas, no lymnaeid snails of any rank or

description volunteered that morning, nor did any evidence thereof present

itself to eyes that ached to see it, not so much as a dry shell.

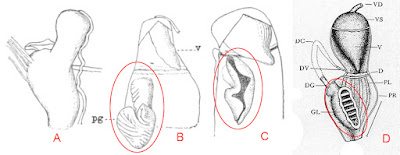

What is the problem here? What is the problem? Too baffled to be dispirited, I returned to my rental car, reversed course back toward town, and crossed the railroad tracks 2,000 m west. There between the tracks and a gravel service road ran a bone-dry ditch choaked with grass, weeds, and roadside litter (B). And in that shallow ditch I found L. bulimoides shells. Lots of them. But none alive – no water.

Returning

to my car and driving another 200 meters west – honestly, I should have walked

– I crossed another agricultural ditch, this one green and carrying water (C). It was marked as an intermittent creek on

USGS maps, much smaller than Spoon Creek, without the habitat diversity. I found sparse populations of both Lymnaea elodes and Helisoma trivolvis in the grasses there, however, and a singleton

individual Succinea grazing along the water’s edge, mimicking an L. bulimoides

so startlingly I almost had a heart attack, three days building [8].

But

absolutely no bulimoides in green ditch (C), nor any shell, nor any sign

thereof. There you have it, in a

triptych. A linear transect of 2,200

meters returned no evidence that bulimoides had ever inhabited a summer-watered

habitat (A), lots of evidence of bulimoides in a summer-dry habitat (B), and no

evidence of bulimoides in a second summer-watered habitat (C). Lymnaea bulimoides populations are obligately

vernal. They cannot be found in the

summer, not in this part of the world, anyway.

But I had time, spirit and wherewithal for one last Hail Mary. Back to the ditch along Bellfountain Road I drove, determined to replicate Greg R. Foster’s experiments from the summer of 1969. I picked a low point near a drainage pipe, where dead shells had accumulated. Then, shiny new Fred Meyer shovel flashing in the hot August sun, I chopped – literally chopped – rock hard earth out of the ditch down to a depth of maybe 10 inches and loaded it into my crisp orange five-gallon bucket. This I carried back to the Airbnb my wife and I had rented in town, hosed down, stirred and waited. Stirred and waited. Stirred. Waited overnight. Nothing.

My wife

and I dropped by Bill’s house on our way out of town the next morning. He had indicated that he could make some use

of a slightly tarnished shovel and a muddy five-gallon bucket, the like of

which I just happened to have in the hatchback of our rental car. Bill promised that he and the OSU students

would monitor G. R. Foster’s Bellfountain Road site, and return in the winter,

with the rains.

I myself

had been completely skunked – humiliated – by Lymnaea (Galba) bulimoides. Even unto the present day, over a

malacological career spanning 50 years, I have yet to see one on the hoof. But tucked into my shirt pocket as we boarded

Delta Flight 675 for home was a glass vial of alcohol. And in that alcohol were exactly N = 2 bona

fide bulimoides from Gahr Pond, courtesy of Ms. Courtney Hendrickson. Might the centuries-old confusion over the

very identity of the Phantom Lymnaeid of the Pacific Northwest somehow yet be

resolved? Tune in next time.

Notes

[1]

Foster, G.R. (1971) Winter vagility of

the aquatic snail Lymnaea (Galba) bulimoides Lea. Basteria 35: 63 – 72.

[2] Den

Hartog, C., and L. DeWolf (1962) The

life cycle of the water snail Aplexa hypnorum. Basteria 26: 61-88.

[3]

Dillon, R.T., Jr. (2000) The Ecology of Freshwater Molluscs. Cambridge University Press, UK. 509 pp.

[4] Wethington, A.R., J. Wise, and R. T. Dillon (2009) Genetic and morphological characterization of the Physidae of South Carolina (Pulmonata: Basommatophora), with description of a new species. The Nautilus 123: 282-292. [pdf] For more, see:

- TRUE CONFESSIONS: I described a new species [7Apr10]

[5] Foster, G.R. (1973) Soil type and habitat of the aquatic snail Lymnaea (Galba) bulimoides Lea during the dry season Basteria 37: 41 – 46.

[6] From

left, Emilee Mowlds, Bill Gerth, Courtney Hendrickson & McKenna Varela.

[7]

Alas, the top off the derelict structure was demolished in 2012, due to

concerns over its structural integrity.

[8] Yes,

in my field notes I wrote, “Succinea gave me a heart attack.” Death by Stylommatophoran. My goodness, we malacologists are a strange

and tender lot, aren’t we?