Editor’s Note – This essay was subsequently published as: Dillon, R.T., Jr. (2023c) Malacological Mysteries: What Was Planorbis glabratus? Pp 319 – 333 in The Freshwater Gastropods of North America Volume 7, Collected in Turn One, and Other Essays. FWGNA Project, Charleston, SC.

In Volume 1 of the Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, Part 2 (June 1818) The Father of American Malacology, Thomas Say, described a new freshwater gastropod as follows [1]:

Planorbis glabratus.—Shell sinistral; whorls about five, glabrous or obsoletely rugose, polished, destitute of any appearance of carina; spire perfectly regular, a little concave ; umbilicus large, regularly and deeply concave, exhibiting all the volutions to the summit; aperture declining, remarkably oblique with respect to the transverse diameter.

Breadth nearly nine-tenths of an inch. Inhabits South Carolina. Cabinet of the Academy.

Presented to the Academy by Mr. L'Hermenier of Charleston, an intelligent and zealous naturalist; he assured me that this species inhabits near Charleston. It somewhat resembles large specimens of the P. trivolvis of the American edition of Nicholson's Encyc., but differs in the total absence of carina, and in having a more smooth and polished surface, as well as a declining and more oblique aperture, and a more profound and much more regularly concave umbilicus.

Alas, Thomas Say did not offer us a figure of his new planorbid species, and alack, all of Say’s type material has been lost. The 139 words I have quoted above are the sum total of everything we know for a fact about Planorbis glabratus.

But to be fair, as strings of 139 words go, Say’s 139 are pretty darn vivid. The adjectives “glabrous” and “polished” effectively distinguish the shell of Say’s new planorbid from his (1817) P. trivolvis [2], widely distributed across North America. “Nine tenths of an inch” is unusually large for a planorbid, and “whorls about five” suggests an exceptionally tight coil.

|

| Planorbis glabratus from Haldeman [3] and Binney [4] |

In any case. Two monographers of the nineteenth century, Haldeman in 1844 [3] and Binney in 1865 [4], took shots at publishing figures of Planorbis glabratus, the former at left above, the latter at right. Neither author offered a scale bar or a measurement, implying a 1:1 reproduction. Both of those figures appear to depict shells with zillions of fine ridges, which make them look suspiciously like dirt common Helisoma trivolvis [5].

Henry Pilsbry wasn’t buying it. We have already reviewed at great length, in three posts to date and counting, The Elderly Emperor’s landmark paper of 1934 [6] describing Seminolina as a new Floridian subgenus of Helisoma and assigning to it four species, including scalare (Jay 1839) and duryi (Wetherby 1879). Pilsbry recognized three subspecies of duryi previously described and added three fresh ones, including a new scalariform (“flat topped”) subspecies seminole, about which we obsessed last month. And he also described a new subspecies at the other end of the spectrum, Helisoma duryi eudiscus, bearing a broad, compressed, tightly coiled shell, shown in the figure below. And he observed:

“This form [eudiscus] is what Bryant Walker [7] and the writer [Pilsbry] called Planorbis glabratus Say. None of the specimens seen approach the dimensions given by Say, and the locality given by him is over 200 miles northward. I have elsewhere discussed the identification of his [Say’s] species.”

H. duryi eudiscus [6]

That “elsewhere” turned out to be “immediately following.” Because the next section of his 1934 paper was headed, “Species Recorded from Florida in Error.” Here Pilsbry elaborated the opinion (first expressed by Wetherby) that neither the shell figured by Haldeman, nor the shell figured by Binney, matched Thomas Say’s original description. And he agreed with Wetherby that South Florida is indeed inhabited by populations of large, flat, shiny, tightly coiled Helisoma that do match Say’s description, which (he had just suggested) might be identified as Helisoma duryi eudiscus. But…

“A difficulty with this identification [of eudiscus as glabrata] is that no such shell has been found in Georgia or in South Carolina (Say’s locality); and there is little probability that a shell from the lower and middle parts of peninsular Florida would have been collected prior to 1818.”

Let me repeat that. That is important. Pilsbry himself, and Bryant Walker, and Albert Wetherby, all thought that the shells borne by planorbid populations Pilsbry was describing as Helisoma duryi eudiscus matched Say’s description of Planorbis glabratus. But Pilsbry did not think that Helisoma duryi ranged as far north as Charleston. And he didn’t know of any eudiscus anywhere reaching a diameter approaching “nine-tenths of an inch” in any case. Remember all that. You’re going to need it after the intermission.

Pilsbry then went on to propose a rather elaborate hypothesis, as follows:

“Say received the type specimen of P. glabratus from Mr. L'Herminier of Charleston, S. C. His description applies well to the Antillean Planorbis guadaloupensis Sowb. I was thus led to inquire into the travels of L'Herminier. I applied to Mr. E. B. Chamberlain, Director of the Charleston Museum, who [confirmed that L’Herminier] came to Charleston about 1814 from Guadeloupe bringing 'an extensive collection of specimens, the fruit of twenty years application, expense and industry, which he offered to the Society [The Literary and Philosophical Society of South Carolina]. Dr. L'Herminier was appointed superintendent or curator of the Society's museum, and served until 1819, at which time he returned to Guadeloupe. […] It seems quite likely therefore that the type of Planorbis glabratus was one of the specimens L'Herminier brought from Guadeloupe, and which he subsequently thought (or Say inferred) that he had picked up around Charleston.”

I know it must seem to you, my loyal and longsuffering readership, that your eccentric guide to malacological triviality most arcane has developed an obsession most inexplicable with an obscure 1934 paper published in the Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, having posted three essays dwelling on the work thus far, plus a large fraction of a fourth essay presently unfolding. Why, you must be wondering, can’t you let those 44 pages of densely-packed esoterica go, Dillon, for God sake? Well, I regret to inform my readership, we haven’t even touched the more important half of Pilsbry’s 1934 paper yet.

Pilsbry’s full title was, “Review of the Planorbidae of Florida, with Notes on Other Members of the Family.” And by “notes,” Pilsbry meant to propose a taxonomic revision of the entire planorbid fauna of the New World.

|

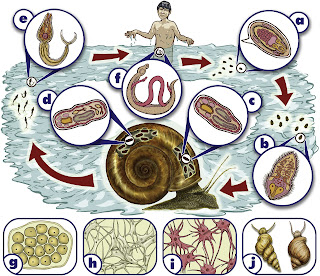

| Australorbis glabratus [6] |

The population of “P. guadeloupensis = A. glabratus” that Pilsbry examined was collected from Puerto Rico. They bore large, flat, shiny, tightly coiled planispiral shells not much different from the Florida populations that he and Wetherby and everybody else had been identifying as Helisoma duryi, especially the subspecies “eudiscus.” But anatomically the Puerto Rico population was quite distinct from Helisoma, missing a penial gland entirely [8].

Both Baker in 1945 [9] and Hubendick in 1955 [10] accepted Pilsbry’s Guadeloupe hypothesis for the origin of Thomas Say’s Planorbis glabratus uncritically, which pretty much set it in concrete, and both accepted Australorbis as a natural genus in which to place it. Baker dissected and figured his sample from Puerto Rico; Hubendick’s came from Venezuela. Baker also gathered a fairly large list of synonyms under glabratus, beyond the guadeloupensis suggested by Pilsbry, including olivaceus (Spix) from Brazil, refulgens (Dunker) from Santo Domingo, lugubris (Wagner) from Surinam, and blauneri (Germain) from Venezuela. So, by 1955, the range of Australorbis glabratus was given as Venezuela to Argentina and throughout the Caribbean.

Yet another taxonomic change was looming, however, even as Hubendick labored over his 1955 monograph. In 1910, the Englishman H.B. Preston had proposed the genus Biomphalaria to hold his new Biomphalaria smithi from the Congo/Uganda border [11], and during the 40 years that followed, momentum built to allocate an increasing number of African species to Preston’s genus. And indeed, species from the New World as well. Hubendick wrote:

"The Biomphalaria tribe includes the following genera: Biomphalaria, Afroplanorbis, Australorbis, Tropicorbis, Taphius, and Platytaphias and probably Syrioplanorbis…The whole tribe is anatomically so homogeneous that it is doubtful if the present separation into genera can be maintained.”

Doubtful, indeed. Begging your indulgence, please allow me to back up and get a fresh start on this entire story, from an entirely fresh perspective [12]. In 1851 the German physician Theodor Bilharz discovered that a widespread and debilitating disease affecting a large fraction of the population of Egypt was caused by a parasitic worm. And in 1915 the Scottish physician Robert Thomson Leiper identified two species of the digenetic trematode genus Schistosoma as the helminthological culprits for two different forms of this same disease and simultaneously worked out the intermediate hosts for both: “Planorbis boissyi” for Schistosoma mansoni and “Bulinus spp” for Schistosoma haematobium.

The form of the disease caused by Schistosoma mansoni had also been a problem for many years in the New World tropics, as well as in the Old. And in 1916, almost immediately after Lieper published his results on Schistosoma mansoni in Egypt, the Brazilian Adolpho Lutz reported the successful development of S. mansoni miricidia in a snail he identified as “Planorbis olivaceus = P. bahiensis.” Then in 1917, the Venezuelan Juan Iturbe obtained similar results with a planorbid population he identified as “Planorbis guadelupensis.”

|

| From Castillo et al. [13] |

Was Pilsbry unaware of Iturbe’s research when he synonymized Planorbis guadelupenis under Australorbis glabratus? Was Baker unaware of Lutz’s work when he did the same thing to Planorbis olivaceus? Neither Pilsbry nor Baker mentioned anything about the parasitological importance of the taxonomic judgements they were making. But together, they made Australorbis glabratus into a Latin binomen that appeared in the abstracts of scores of papers directly bearing on issues of human health through the 1940s into the early 50s.

By 1955, Hubendick did think it worth mention that “several planorbids act as intermediate hosts for many trematodes, including schistosomes” in his introduction, although he did not hear the call to develop that theme until the 84th page of his 90 page work. There he reiterated his opinion that Australorbis (and Tropicorbis) did not differ “in any essential way” from Biomphalaria (or Afroplanorbis). But he continued, “although the most natural course would be to unite all the genera into one genus,” to do so “would certainly cause much confusion and trouble to works in medical parasitology who are now familiar with names which are in current use.” Thus, Hubendick advocated retaining glabrata (Say 1818) in Australorbis.

All I can figure is that by the time he wrote those words, Hubendick had already been out-voted. Because in 1954 the World Health Organization had convened an international “Study-Group” consisting of Alves, Berry, Hubendick, LeRoux, Mandahl-Barth and Ranson. And by 1955, the joint opinion of the group had been published [14]:

“It has long been recognized that the known species which serve as the intermediate hosts for S. mansoni are genetically the same and that all have probably been derived from common stock. It was therefore agreed that these and their related species should be united into a single genus Biomphalaria, and that the genera Australorbis, Afroplanorbis, and Tropicorbis should be considered synonyms.”

And all other researchers worldwide fell in line. So today, a quick reference to the NCBI PubMed database returns 3,438 hits to the search term “Biomphalaria glabrata,” the intermediate host of schistosomiasis in the New World, 1947 to present.

OK, I’m going to take a 20-minute break for some fresh air. While I’m gone, here’s a question for your consideration. What would happen if Thomas Say’s sample of Planorbis glabrata really was collected from Charleston, as he was assured by that “intelligent and zealous naturalist,” Felix L'Hermenier? Discuss amongst yourselves …

… and I’m back. I just drove over to Charles Towne Landing State Park, about a mile from my house here in the West Ashley neighborhood of Charleston. They have a couple pretty little spring-fed lakes over there. And the figure below shows what I found.

These shells are a near-perfect match to every word in Thomas Say’s 1818 description of Planorbis glabratus, and don’t tell me that they aren’t. They are “destitute of any appearance of carina,” “polished” to the point of “glabrous.” Their spires are (indeed) “a little concave, umbilicus large,” and apertures (indeed) “remarkably oblique.” The diameter of the middle specimen, viewed edge-on, is 22.6 mm = 0.89 inch.

This is the "Population C" I sampled for our colleague Cindy Norton back in 2018. My readership will remember that Cindy's breeding experiments returned no evidence of reproductive isolation between population C and a sample of Helisoma scalare scalare (“F”) I collected for her from way down in the Florida Everglades [15]. So, since the shells borne by Population C are planispiral, the most modern, least-controversial identification for the Charles Towne Landing population is currently Helisoma scalare duryi [16].

|

| Charles Towne Landing SP |

The figure at the top of the montage down below was borrowed from a [29Nov04] essay I wrote about a gigantic Helisoma population inhabiting an ornamental pond outside a commercial office park here West of the Ashley, about a mile from Charles Towne Landing. And the two figures beneath it were borrowed from a [18Feb05] essay I wrote about a dimorphic Helisoma population in a subdivision called “Wakendaw Lakes” in Mt Pleasant, a Charleston suburb east of the Cooper River. I initially identified both of those populations as “Helisoma trivolvis,” back before the scales fell from my eyes in 2021 [17], but their best modern identification would again be Helisoma scalare duryi, same as the Charles Towne Landing population.

Pilsbry and Baker would almost certainly have identified the shells from Charles Towne Landing State Park above as Helisoma duryi normale [16]. Those from the office park and the Wakendaw Lakes subdivision below I feel fairly certain would have been Helisoma duryi eudiscus. And both Pilsbry and Baker would have been shocked to learn that any planorbid populations bearing shells of such flamboyantly duryi morphology might inhabit waters anywhere north of Florida [18].

But in fact, I am now aware of six populations of H. scalare duryi in Charleston County alone, and many others scattered elsewhere around coastal South Carolina as far north as the vicinity of Myrtle Beach, and three in coastal Georgia as well [19]. Plus, Binney’s historic record from St. Simon’s Island, GA, brings the Georgia populations up to four [5].

Although most of the Carolina and Georgia populations of H. scalare duryi of which I am aware inhabit disturbed environments today, my biological intuition suggests to me that this northern end of their range is as natural as their southern one. Binney’s collection dates prior to 1865. But even if the occurrence of Helisoma scalare duryi here in the Charleston area is artificial, if the introduction occurred prior to 1818, the point I am trying to argue will not be affected.

|

| Office Park & Wakendaw |

So by the letter of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, all those Floridian nomina of planorbids: scalare (Jay 1839), duryi (Wetherby 1879), and all the subspecies proposed by Pilsbry and others, like eudiscus and seminole, are junior synonyms of glabrata (Say 1818). Which means that by the letter of the Code of Zoological Nomenclature, all those tropical planorbid populations that host Schistosoma mansoni in the New World, originally identified as guadeloupensis (Sowerby), olivacea (Spix) and many other names [20], are not correctly identified as Biomphalaria glabrata. They must be called something else. I don’t know what. I don’t want to know.

Because what I have uncovered here is a bomb. Actually, it’s more like one of those rusty old artillery rounds that utility crews still occasionally dig up under the streets of Charleston, fired by Union cannon during the bombardment of 1863-65. It’s a dud. That old thing can’t possibly be dangerous, can it?

Well, yes, it can. I myself was caught in the shrapnel when Jack Burch unearthed just such a dud in the early 1980s [22]. The genus Elimia was shot into the air by H & A Adams in 1854 to contain an odd-lot assortment of pleurocerid nomina, hit the ground with a thud, and was buried and forgotten for 120 years, explicitly rejected by Tryon, Walker, Goodrich, and all other authorities of the day in favor of Isaac Lea’s Goniobasis. But even as I was defending my dissertation on Goniobasis in Philadelphia, Jack Burch was exhuming Elimia in Ann Arbor and synonymizing Goniobasis underneath it. This he did for no scientific reason whatsoever, motivated entirely by a sense of romantic duty to the Code of Zoological Nomenclature. The confusion and misunderstanding persist to the day [23].

So, it turns out that when Charleston utility crews unearth unexploded Yankee ordinance, no matter how old and decrepit the round might be, they don’t rebury it. They call the bomb squad. And the bomb squad doesn’t try to “defuse” that rusty old thing in some fine and sophisticated manner. They just blow it up.

So, this month I have spent 3,028 words digging up a rusty old bomb called “Planorbis glabratus.” I now mean to blow it up. Planorbis glabratus Say 1818 must remain a senior synonym of Planorbis guadeloupensis Sowerby, 1822, as proposed by Pilsbry in 1934, and senior as well over all tropical and Caribbean planorbid taxa more recently described and subsequently placed underneath it [20]. To redefine Say’s 1818 taxon as a senior synonym of John Clarkson Jay’s 1839 Paludina scalaris or Wetherby’s 1879 Helisoma duryi would be a terrible disservice to the cause of science. I won’t do it, and don’t any of the rest of you try.

Because here’s the important thing. And I am dead serious about this, so listen up. Biological nomenclature must serve science. To change the specific name by which we have referred to the intermediate host of schistosomiasis in the New World would create epic levels of confusion, mischief, and mayhem for absolutely, utterly no reason other than an obscure point of law. Biomphalaria glabrata must remain Biomphalaria glabrata, as that taxon is currently understood by the scientific community, for the sake of science, now and forever, amen.

Notes

[1] Say, T. (1818) Account of two new genera, and several new species, of fresh water and land shells. Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 1(2): 276 – 284.

[2] The shell of Helisoma trivolvis is “thread striate,” noticeable especially in juveniles, which tends yield a duller luster. See:

- Collected in Turn One [5Jan21]

[3] Haldeman, S.S. (1844) [not “1841”] A monograph of the freshwater univalve Mollusca of the United States, Number 7 Philadelphia: Cary & Hart, Dobson, and Pennington. 32 pp, 4 plates.

[4] Binney, W.G. (1865) Land and fresh water shells of North America Part II, Pulmonata Limnophila and Thalassophila. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections 143: 1 – 161.

[5] Haldeman’s specimen came from “Mexico (?)” and Binney’s specimen came from St. Simon’s Island, GA, which means, ironically, that Binney’s (at least) was almost certainly correctly identified as Planorbis glabratus, in the contemporary meaning of that name. Read on and see footnote [17].

[6] Pilsbry, H. A. (1934) Review of the Planorbidae of Florida, with notes on other members of the family. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 86: 29 – 66. For a review, see:

- The Emperor Speaks [3Dec20]

- The Emperor, the Non-child, and the Not-short Duct [9Feb21]

- New Clothes for The Emperor [7Feb23]

[7] Walker, B. (1918) A synopsis of the classification of the freshwater Mollusca of North America, North of Mexico, and a catalogue of the more recently described species, with notes. Univ. Mich. Mus. Zool. Misc. Publ. 6: 1 - 213.

[8] The distinction between Pilsbry’s new genus Australorbis and his previously described Tropicorbis was negligible, however. And I quote: “P. guadaloupensis differs from Tropicorbis by its extremely short almost sessile spermatheca, the relatively shorter upper sac of the penis, and by the denticulation of the marginal teeth, in which the denticles remain widely separated in an inner and an outer series.” Good grief.

[9] Baker, F.C. (1945) The Molluscan Family Planorbidae. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. 530 pp.

[10] Hubendick, B. (1955) Phylogeny in the Planorbidae. Trans. Zool. Soc. London 28: 453-542.

[11] Preston, H. B. (1910). Additions to the non-marine molluscan fauna of British and German East Africa and Lake Albert Edward. The Annals and Magazine of Natural History. (8) 6 (35): 526-536, pl. 7-9.

[12] I thank Sam Loker for pointing me to an excellent reference on the history of schistosomiasis research, upon which I have based the brief review above:

- Grove, David I. (1990) A History of Human Helminthology. C.A.B.International, Wallingford.

[13] Castillo, M.G., J.E. Humphries, M.M. Mourao, J. Marquez, A. Gonzalez, C.E. Montelongo (2020) Biomphalaria glabrata immunity: Post-genome advances. Developmental & Comparative Immunology 104: 103557.

[14] Alves, W., E.G. Berry, B. Hubendick, P.L. LeRoux, G. Mandahl-Barth, and G. Ranson (1954). Bilharzia snail vector identification and classification (Equatorial and South Africa). Report of a Study-Group. World Health Organization Technical Report Series 90: 1 – 24.

[15] For the complete story of Cindy Norton’s breeding experiments, read this series of essays:

- The Flat-topped Helisoma of The Everglades [5Oct20]

- Foolish Things with Helisoma duryi [9Nov20]

- Collected in Turn One [5Jan21]

[16] I just proposed lowering Wetherby’s (1879) duryi to subspecific status under Jay’s (1839) scalaris last month. But the build-up was a lengthy one, extending back to early 2021. Work backwards from this essay if you want the complete

- New Clothes for the Emperor [7Feb23]

[17] Although I reported the “scales falling from my eyes” regarding the Charleston area Helisoma populations in January of 2021, the build-up was a lengthy one, extending back to 2018. Work backwards from this essay if you want the complete story:

- Collected in Turn One [5Jan21]

[18] In my dreams, I march right up to Philadelphia with a Charleston sample of Helisoma scalare duryi under my arm and present it to Henry Pilsbry. He accepts it, thanks me, and writes, “another notorious liar” on the back of the label.

- Dr. Henry A. Pilsbry was a Jackass [26Jan21]

[19] Toward the bottom of my 5Jan21 essay, I mentioned “one population of H. duryi in coastal Georgia" as well as “15 populations in coastal South Carolina.” More recently I have discovered two additional populations of H. scalare duryi in Savannah, bringing the coastal Georgia count up to three.

[20] Here’s a list of junior synonyms that have been placed under glabrata (Say 1818), collected both from Baker [9] and from Malek [21]: guadeloupensis (Sowerby), christopherensis (Pils), olivaceus (Spix), refulgens (Dunker), lugubris (Wagner), blauneri (Germain), ferrugineus (Spix), nigricans (Spix), albescens (Spix), viridis (Spix), lundii (Beck), cumingianus Dunker, becki Dunker, bahiensis Dunker, and xerampelinus Drouet.

[21] Malek, E. (1985) Snail hosts of schistosomiasis and other snail-transmitted diseases in tropical America: A manual. Washington, D.C., Pan American Health Organization. 325 pp.

[22] For a complete review of the controversy, see:

- Goniobasis and Elimia [28Sept04]

[23] The controversy should have ended in 2011, when I formally synonymized both Goniobasis and Elimia under Pleurocera, but it did not. See:

- Goodbye Goniobasis, Farewell Elimia [23Mar11]