Editor’s Notes - If you’re just joining us, I apologize. This month’s blog builds from a series of eleven essays on the morphology, systematics, ecology and biogeography of the planorbid genus Helisoma in the southeastern United States, stretching all the way back to 2004, as listed at footnote [1] below. No, you don’t have to read that entire list, unless you are seriously interested in the science. But the story below won’t make any sense at all unless my two most recent essays, [6Dec22] and [5Jan23], are fresh in your mind. Oh, and all that anatomical mishmash I reviewed two years ago, in [9Feb21] will be super helpful for this month’s essay, as well.

This essay was subsequently published as: Dillon, R.T., Jr. (2023c) New Clothes for The Emperor. Pp 307 – 317 in The Freshwater Gastropods of North America Volume 7, Collected in Turn One, and Other Essays. FWGNA Project, Charleston, SC.

Both Helisoma scalare and Helisoma duryi were described in the 19th century from “The Everglades of Florida.” Both of their type localities were, however, hundreds of miles north of the ecological region formally recognized as The Everglades here in the 21st. And none of the 20th century monographers who reviewed the planorbid gastropods in the interim: Henry Pilsbry [2] in 1934, F. C. Baker [3] in 1945, or Bengt Hubendick [4] in 1955, had on his lab bench any live-collected topotypic material for either nominal species. And as I merged into the eastbound lanes of I-10 on Tuesday morning Feb 23, 2021, Tallahassee in my rearview mirror, neither did I.

Both Pilsbry and Baker based their extensive and detailed redescriptions of Helisoma scalare on a population of planorbids sampled from “Lake Butler, Pinellas County.” In 1949 the Florida legislature changed the name of that particular body of water to “Lake Tarpon” to mitigate confusion with another Lake Butler elsewhere in The Sunshine State. And so, it was the coordinates of a boat launch in the John Chestnut Park on the SE shore of Lake Tarpon, about 15 miles NW of Tampa, that I had keyed into the GPS on my dash that cloudy February morning.

|

| Helisoma scalare from Lake Tarpon (nee Butler) |

And the body of water into which I launched my kayak some four hours later, light drizzle notwithstanding, was a lovely lake of 2,500 acres, average depth 8 feet, clear and cool and blessed with an abundance of macrophytic vegetation of all sorts: floating, emergent, and submerged. And the weeds of that last-listed category, wafting in the gentle currents at depths of an arm’s length, were laden with Helisoma scalare bearing shells of a most gratifyingly classic morphology, as depicted in the figure above.

The situation in Lake Tarpon (nee Butler) turned out to be quite reminiscent of that I described in The Everglades at the 40-Mile-Bend a couple years ago [5Oct20]. The flat-topped Helisoma seem to reach maximum abundance in the rooted-submerged macrophytes in both places, especially inside beds of eel grass (Vallisneria). I also noted high densities around the roots of emergent vegetation, such as cat tails (Typha). The snails do not seem to crawl up those Typha stems to the surface under any circumstance, however. Their life habit appears exclusively benthic.

Indeed, during the couple hours I waded and kayaked around the margins of Lake Tarpon, I developed the strong impression that no element of the entire population of Helisoma dwelling therein ever, from its birth to its death, rose to enfold an air pocket under its mantle, under any circumstance. This suggested to me that they would not adapt well to warming or artificial enrichment, or to any perturbation that might cause levels of dissolved oxygen to dip in their lovely lacustrine environment. Helisoma scalare populations seem to need large volumes of cool, clean, clear water.

Such a situation contrasts strikingly with the typical habitat of Helisoma duryi in my experience, or (indeed) Helisoma trivolvis throughout the remainder of North America. Populations of more typically-planispiral planorbids are ordinarily found grazing in floating macrophytes in warm, rich ponds or ditches, or on the margins of riverine backwaters, almost always near the surface.

|

| Lake Tarpon |

And back wading in Lake Tarpon, I also developed the strong impression that, setting aside their peculiar scalariform morphology, the shells borne by this particular population of pulmonate snails were exceptionally thick, heavy, and robust. This seemed to imply some special adaptation for defense against crushing predation. At this suggestion, the schools of bream darting about in the clear waters around my feet seemed to nod their heads in agreement.

The skies were growing leaden over the crystalline waters of Lake Tarpon as I loaded my kayak back into my pickup and pushed the button on my GPS unit for home. And the next afternoon I dumped my big, fresh sample of H. scalare in an enamel pan on my lab bench and pulled out the big samples of H. duryi I had collected in 2020. And I opened my well-thumbed copy of Pilsbry 1934 on the left side of my lab bench, and my much-beloved copy of Baker 1945 on the right. And to refresh everybody’s memory:

In 1934 “The Elderly Emperor” gathered four previously described species of Floridian planorbids into a new subgenus of Helisoma he called Seminolina: scalare (Jay 1839), duryi (Wetherby 1879), and two fossil species of Dall (1890), conanti and disstoni. Under Helisoma (Seminolina) duryi he recognized six subspecies: the typical H. duryi duryi (Wetherby), intercalare (Pilsbry 1887), preglabratum (Marshall 1926), and three new ones: normale, eudiscus, and seminole. Together this set of six subspecific nomina described a completely seamless progression from the compressed, tightly-planispiral eudiscus to the typical, loosely-planispiral duryi to the flat-topped, scalariform seminole.

|

| From Pilsbry [5] |

But to be clear. Pilsbry did not subscribe to the modern convention that subspecies demonstrate any sort of geographical isolation. He wrote:

“In a well-watered region of low relief, like Florida, no barriers to the migration of these snails exist, so that the geographic limits of such races are only vaguely defined. The shell characters are so variable that with single shells or small series the identity may often be in doubt.”

In the image below, clipped from Pilsbry’s Plate 7, the top row of shells (5a – 5f) were all borne by a Helisoma duryi population sampled from “near Lake Apopka,” the second row (6a – 6f) all from a population inhabiting Lake Eustis (Lake Co.), and the third row (7a – 7e) all from the Head of the Miami River. This entire set of 17 shells he identified as varying subspecies of Helisoma duryi. There is no difference between shells 5e, 5f, 6e, 6f, and any of the shells I collected from Lake Tarpon.

So again, I ask. If not the shell morphology, what exactly is the difference between Helisoma duryi – particularly the subspecies that Pilsbry began calling H. duryi seminole in 1934 – and the earlier-described H. scalare? The distinction that Henry Pilsbry drew in 1934 turned out to be entirely anatomical. The duryi/scalare situation is very closely analogous to the duryi/trivolvis situation we reviewed at great length back on [9Feb21], involving many of the same anatomical features, and (indeed) the same illustrations of them. So to refresh everybody’s memory, again:

It was upon Henry Pilsbry’s head that rested the crown of American Malacology, pretty much his entire career, from 1887 to 1957. Frank Collins Baker, more experienced as a field biologist and more gifted as a scientist, studied under Pilsbry in 1889, and labored in his shadow thereafter, predeceasing his mentor by 15 years. And to understand what I’m getting ready to tell you about scalare and duryi, you need to understand the relationship between Pilsbry and Baker. A bit of familiarity with the reproductive plumbing of pulmonate gastropods will also be helpful, but not necessary.

|

| From Pilsbry [2] Plate 7. |

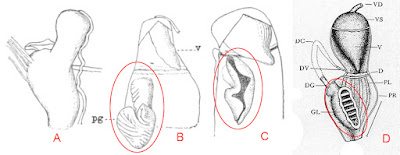

When not in use, pulmonate gastropods invert their penis – turn it outside in – to make a bag with the business end inside. Figure (A) in the montage below shows the structure that Pilsbry (1934) simply called the Helisoma scalare “penis, unopened.” It’s an (upside down) sack, with an opening in the bottom through which the penis everts for copulation. The figure I’ve marked (B) shows a Helisoma scalare penis sack opened, Pilsbry’s “V” standing for “verge,” which is a polite name for the business end of the penis during copulation. And the organ Pilsbry has marked “pg” is the penial gland, which presumably supplies some sort of lubrication during copulation, or stimulation, heaven knows.

So, to distinguish the two nominal species of the subgenus Seminolina, scalare and duryi, Pilsbry focused exclusively upon differences he perceived in the penial gland. In his description of his new scalariform subspecies H. duryi seminole, he wrote:

“I dissected specimens collected many years ago in Polk Co., Florida, by S. Hart Wright, and similar in shape to fig. 6d of Plate 7. The bodies are brittle, and only the penis was examined (figure C), cylindric, with the upper sac divided off inside by a thin rather high ridge. The stout conic verge projects into the lower sac. The penial gland is oblong with the smooth lateral borders folded in the alcoholic specimens, as in figure (C). This structure is quite unlike that found in H. scalare (B).”

And to reinforce the distinction, here is what Pilsbry said in his redescription of H. scalare:

“In the specimens of H. duryi seminole opened, the penial gland was found to differ [from H. scalare] in important details. It [the duryi penial gland] has a broad oblong face directed toward the cavity, with the lateral borders infolded in alcoholic specimens, as in figure (C). The division between upper and lower sacs of the penis is a single rather high thin ridge. The stouter shape of the verge in H. d. seminole may be due to greater contraction, as the specimens had evidently been killed in strong alcohol.”

Now moving forward ten years. In addition to the three Pilsbry figures I have reproduced below F. C. Baker’s (1945) figure of the same organ – less artistic but more scientific (D). Baker did not execute separate drawings for scalare and duryi. This single figure was offered to represent the entire subgenus Seminolina, including scalare and duryi of all subspecies.

|

| Penial complexes from Pilsbry [2] and Baker [3] |

Baker dissected 35 individuals from the “Lake Butler” (now L. Tarpon) population of H. scalare, and populations of H. duryi from seven different sites, representing three subspecies. Regarding the Lake Tarpon population, Baker was quick to pay homage to the Elderly Emperor:

“The genitalia of Helisoma scalare examined agree perfectly with the figures published by Pilsbry 1934.”

Turning to his H. duryi samples, Baker figured on his Plate 33 the “penial complexes” (Pilsbry’s “penis unopened”) from 12 different H. duryi individuals dissected from four populations of three different subspecies, all pushed, pulled, shrunk and extended into a myriad of diverse, blobby profiles. And hidden among his observations was this single-line bombshell, directly contradicting the only distinction that Pilsbry had ever drawn between scalare and duryi:

“The penial gland in the duryi complex is of about the same shape as that organ in scalare.”

Poor Frank Collins Baker! I can still feel the anguish seeping from page 132 of his planorbid monograph, here 80 years later. The character of the penial gland that Pilsbry called “lateral borders infolded” is trivial at best, entirely artifactual if it ever existed. Baker couldn’t confirm it in a dozen H. duryi sampled from four populations. But neither could he risk offending his Emperor. So, all he could do was to dissemble, which he did, five sentences later:

“The figures of the duryi complex agree with those by Pilsbry (1934). As Pilsbry remarks on page 36, the anatomical differences are sufficient to separate scalare from duryi and its races.”

The bottom line for us today is, however, that there is no evidence of any morphological distinction whatsoever, shell or anatomical, heritable or otherwise, let alone any evidence of reproductive isolation, between the diverse planorbid populations found throughout Florida and around the world conventionally identified as Helisoma (Planorbella) duryi, and the earlier described planorbid populations of deeper, cooler and cleaner Floridian waters identified as Helisoma (Planorbella) scalare. Wetherby’s (1879) nomen duryi is a junior synonym of Jay’s (1839) scalaris or scalare [7].

But let’s save duryi at the subspecific level to describe populations of H. scalare bearing planispiral shells, shall we? I hasten to remind everybody, once again, that the FWGNA has adopted the definition of the word subspecies in currency since the birth of the modern synthesis: “populations of the same species in different geographic locations with one or more distinguishing traits.” No additively heritable basis for the shell morphological distinction between the typical scalariform morphology and the planispiral duryi morphology is necessary, or implied [8].And I also hasten to remind my readership that the “different geographic locations” may differ at very small scales in freshwater gastropods. See my essay of [18Feb05] for an example here in the Charleston area where populations of the duryi subspecies and the typical subspecies are separated by only a few meters.

As we have seen, the most obvious correlation seems to be with the habitat: scalariform populations inhabiting submerged macrophytes and benthic substrates in large, permanent clearwater lakes and springs absent contact with the surface, planispiral populations inhabiting emergent or floating macrophytes on the margins of ponds, ditches and riverine backwaters.

There is also a correlation with predator pressure: the scalariform populations of clearwater lakes suffering more fish predation, the planispiral populations more beset by invertebrate predators like crayfish and leeches. And trematode parasites, apparently. For completeness, here’s an interesting observation from Baker, page 134:

“The Helisoma duryi complex includes several races more or less heavily infested with parasitic worms. These include normale, intercalare, eudiscus, and duryi. Many specimens were so badly infested that most of the organs, especially the genitalia, were completely obliterated. Helisoma scalare was the least affected.”

In conclusion. Nothing I have written in this essay is intended as a criticism of Henry Pilsbry or (heaven forbid!) Frank Collins Baker, both of whose works stand today at the pinnacle of classical American malacology [9]. Pilsbry was The Emperor, and if in his judgement some wrinkle or fold in some gland or tube confirmed the specific status of some gastropod population somewhere, in late pre-modern systematic biology, that settled it. Baker was a courtier, following in retinue behind.

I’d like to imagine myself in the story as a small boy watching the grand parade, naively observing that even if the margins of some particular gland in some particular snail really were folded in the particular fashion The Emperor decreed, naturally and not the result of some sort of artifact, it just wouldn’t matter anyway.

But alas, The Emperor, his Retinue and his Grand Parade have long, long passed, many years ago. And I’m just sweeping up behind.

Notes

[1] Here’s a complete list of all essays previously posted on this blog relevant to the argument I am advancing this month:

- Gigantic pulmonates [29Nov04]

- Shell morphology, current, and substrate [18Feb05]

- Juvenile Helisoma [9Sept20]

- The Flat-topped Helisoma of The Everglades [5Oct20]

- Foolish things with Helisoma duryi [9Nov20]

- The Emperor Speaks [3Dec20]

- Collected in turn one [5Jan21]

- Dr. Henry A. Pilsbry was a jackass [26Jan21]

- The Emperor, the Non-child, and the Not-short Duct [9Feb21]

- In the Footsteps of the Comte de Castelnau [6Dec22]

- The Helisoma from the Black Lagoon! [5Jan23]

[2] Pilsbry, H. A. (1934) Review of the Planorbidae of Florida, with notes on other members of the family. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 86: 29 – 66.

[3] Baker, F. C. (1945) The Molluscan Family Planorbidae. University of Illinois Press, Urbana. 530 pp.

[4] Hubendick, B. (1955) Phylogeny in the Planorbidae. Trans. Zool. Soc. London 28: 453-542.

[5] This is quite possibly the most famous figure Pilsbry ever published. It depicts the only overtly evolutionary thought that ever flickered through The Elderly Emperor’s mind, as far as I know. It was reproduced on page 280 in Burch [6], and I dredged it up again for my Helisoma essay of [18Feb05].

[6] This is a difficult work to cite. J. B. Burch's North American Freshwater Snails was published in three different ways. It was initially commissioned as an identification manual by the US EPA and published by the agency in 1982. It was also serially published in the journal Walkerana (1980, 1982, 1988) and finally as stand-alone volume in 1989 (Malacological Publications, Hamburg, MI).

[7] Pilsbry re-spelled the feminine scalaris to the neuter scalare to agree in gender with the neuter noun-construct Helisoma. His Imperial Majesty did not stoop to explain that fine point of Latin grammar himself, however. My good buddy Harry Lee was much more helpful.

[8] For a complete discussion of the subspecies concept as adopted by the FWGNA project, see:

[9] Neither Pilsbry nor Baker was touched by the modern synthesis, although I’d like to think that Baker would have been receptive, had he survived beyond 1942. This makes the 1934 work of Calvin Goodrich [10] all the more impressive, if you think about it, am I right?

[10] For an appreciation of Calvin Goodrich, see his brief bio, then review his 1934 masterwork:

- The Legacy of Calvin Goodrich [23Jan07]

- CPP Diary: The spurious Lithasia of Caney Fork [4Sept19]

- Intrapopulation gene flow: Lithasia geniculata in the Duck River [7Dec21]

Brilliant. This is what testing taxon concepts is all about. This is why taxonomy is science. The pervading question of what constitutes the limits of a given taxonomic concept is the fundamental argument attributed to the so called “lumpers” and “splitters”. Instead, it is between those who refuse to abandon traditional nomenclature for reasons of their own and those who would use character analyses to make taxonomy more a useful system that is ultimately converging with biological reality. The great coleopterists Bob Gordon and Paul Skelley (2007) wrote: "Systematics utilizes four different processes to arrive at a finished product. Taxonomy is the art of recognizing and describing different taxa. Nomenclature is the codified practice we follow to name perceived taxa. Phylogenetics is one of several scientific methods used to gain an understanding of evolutionary history. In practice, it is an art to choose informative characters, code them appropriately, and decipher the multiple trees produced. Classification is the organizing of nature into a hierarchical system of names, a filing system, hopefully based on evolutionary history. The art in classification is deciding where to draw limits in the perceived evolutionary history and then officially name the various branches. The art of taxonomy is aided with the rigors of well-practiced phylogenetics."

ReplyDeleteThanks for your kind words! Regarding the Gordon & Skelley quote, I might have added something about direct testing of reproductive isolation at the species level. But that would force an unlovely interruption into an otherwise lofty pronouncement.

DeleteOh, yeah: I love the old Rocky & Bullwinkle show nod at the end!!

ReplyDeleteYes, that little man sweeps up after "Peabody's Improbable History" parade 1959 - 1963. Ah, the days of my youth!

Delete