Editor’s Note – This essay was subsequently published as:

Dillon, R.T., Jr. (2023b) CPP Diary: The Spurious Lithasia of Caney Fork. Pp 9 - 15 in The Freshwater Gastropods of North America Volume 6, Yankees at The Gap, and Other

Essays. FWGNA Project, Charleston, SC.

The Duck River is our Galapagos, and Calvin Goodrich our

Darwin. Or possibly our

inverse-Galapagos, and our anti-Darwin, I’m not sure. For the brilliant evolutionary insight that

Goodrich glimpsed in 1934 through the lens of this rich, fresh waterway coursing

through the heart of middle Tennessee was not more species, but less.

It’s an old, old story [1], but let’s tell it again. Prior to the dawn of the modern synthesis,

North American freshwater malacology recognized at least 12 – 15 species of

pleurocerids in the Duck River, probably more.

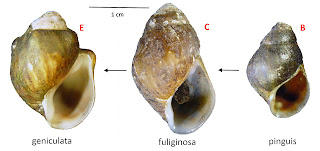

The lower reaches of the Duck (e.g., Wright Bend site E) were inhabited

by heavily-shelled, “obese” populations identified as Lithasia geniculata,

distinguished by their shells with prominently-shouldered whorls. The slightly-less-obese, smooth-shouldered

populations of the middle reaches (e.g., US41A, at site C) were identified as

Lithasia fuliginosa. And the headwaters

of the Duck River (e.g., Old Fort site B) were inhabited by Anculosa pinguis,

lightly-shelled populations without any shoulders on their whorls at all.

|

| CPP in the Lithasia geniculata of the Duck River |

In 1934, Goodrich published his “Studies of the Gastropod

Family Pleuroceridae I,” in which he synonymized all these forms as subspecies

under L. geniculata [2]. He just did it,

at the top of the section, without making any sort of declaration, or using any

form of the noun “synonym,” as though his unique insight were already an

article of established malacological doctrine [3]. He then meticulously documented, town to town

and bridge to bridge down the length of the Duck, the gradual transition of the

three subspecies from one form to the next.

Even to me, his latter-day apostle, Goodrich’s 1934

intuition about the plasticity of shell phenotype in freshwater gastropods was

startlingly profound. His “Studies in

the Gastropod Family Pleuroceridae” series inspired me to coin the term

“Goodrichian taxon shift” in his honor in 2007, subsequently generalized to

cryptic phenotypic plasticity (CPP) by Dillon, Jacquemin and Pyron in 2013 [4].

So, six years later, Goodrich published a paper reviewing

the taxonomy and distribution of the pleurocerid fauna of the Ohio River

drainage in its entirety, not just the Lithasia of the Duck River but all

species in all seven genera in a vast region touching 14 states [5]. And the only other population of Lithasia

geniculata pinguis of which he was aware inhabited the Caney/Collins drainage

of the Cumberland River, the headwaters of which interdigitate with the Duck

immediately to the east, in the vicinity of McMinnville.

But alas, even in Goodrich’s day the diverse pleurocerid fauna of the Tennessee/Cumberland was rapidly disappearing in the face of impoundment, canalization, and widespread development for navigation and hydropower across the southern interior. The Caney/Collins system was terribly impacted by the impoundment of Center Hill Lake in the late 1940s, and the same almost happened in the Duck River in the 1970s, themes to which we shall return. Motivated by longstanding conservation concerns, in 2003 our colleagues Russ Minton and Chuck Lydeard undertook to construct a gene tree for the North American genus Lithasia [7].

Russ and Chuck a good job rounding up

samples from 11 of the species and subspecies of Lithasia listed by

Goodrich/Burch, 25 populations in all, sequencing in some cases as many as 6

individuals per population. From the

Duck River Russ and Chuck sequenced one population of L geniculata geniculata

(1 individual), three populations of L. geniculata fuliginosa (1, 3, and 3

individuals), and one population of L. geniculata pinguis (6 individuals). And they also included 2 individuals of

nominal Lithasia geniculata pinguis from a Caney/Collins population. And here is their gene tree:

|

| Minton & Lydeard [7] Figure 3, modified. |

By now my readership will understand gene trees are

dependent variables, not independent variables [8]. You cannot work out the evolution of a set of

organisms from a gene tree. But if you

have developed an evolutionary hypothesis from good solid data of some broader

sort, you may be able to understand what a gene tree is telling you.

To completely unpack the message being telegraphed to us by

the enigmatic arboreal specimen figured above would require at least 6 – 8 blog

posts of standard length [9]. But for

the present let us focus on just the two little branches labelled “geniculata

pinguis” that I have circled in red. The

two sequences obtained from the 6 individuals sampled from the Duck River, D1

and D2, cluster with all the other Lithasia.

And the two sequences obtained from the Caney/Collins system, C1 and C2,

are way off with pleurocerids of other genera.

To quote Minton & Lydeard verbatim: “Further work needs to be

undertaken to determine the identity and placement of the Collins River taxa.”

Thanks, Captain Obvious! If Calvin Goodrich had enjoyed access to collections from

the Caney/Collins system of the same quality and detail that he enjoyed for the

Duck, he might well have recognized a gradual progression in the shell

phenotype of Pleurocera simplex quite analogous to that he documented for

Lithasia geniculata in 1934.

Most of the headwaters of Caney Fork and its tributaries

(e.g., site J) are inhabited by rather typical-looking populations of the

widespread Pleurocera simplex simplex, no different from those one might find

in tributaries of the Holston River around Saltville, VA, from whence the

species was described by Thomas Say in 1825 [11]. We featured the P. simplex population

inhabiting Pistol Creek at Maryville, TN in a series of essays published in 2016 [12], and the P.

simplex population inhabiting Gap Creek, TN, last month [13]. All of these populations are darkly

pigmented, and bear gracile, teardrop-shaped shells such as shown in figure J

below.

And all those populations inhabit small creeks and streams

primarily of groundwater. In East

Tennessee, populations of Pleurocera simplex do not typically extend into

larger rivers [14].

But in tributaries of the Cumberland, Kentucky, and Green

Rivers, Pleurocera simplex populations often do extend into rivers of

substantial size – as long as the currents are good and the rocky substrate they require does not

entirely give way to mud. Here their

shells become heavier, chunkier, and more lightly-pigmented. Goodrich [5] identified paler,

heavier-shelled populations such as are found in the Collins River at site K as

“Goniobasis ebenum (Lea 1841).”

And in the largest rivers of the Caney/Collins system (e.g.,

site L), populations of P. simplex are so robustly shelled that they can easily

be confused for Lithasia geniculata pinguis.

I speculate it may have been a sample of P. simplex that Minton & Lydeard

collected from the Collins River back in 2003, demonstrating intrapopulation

morphological variance so extreme as to prompt an (erroneous) identification of

Lithasia.

To be clear. Bona

fide populations of Lithasia geniculata pinguis do indeed inhabit the

Caney/Collins system, as Goodrich stated.

But they are typically sparse, and often swamped by dense populations of

P. simplex. Pleurocera simplex

populations do not range west into the Duck River drainage, however, and so

confusions of this sort did not complicate the story Goodrich told us in 1934.

So broadening the subject out through the rest of Middle Tennessee and into Kentucky. What is this enigmatic taxon described by Isaac Lea in 1841, "Melania" (aka Goniobasis, aka

Elimia, aka Pleurocera) ebenum? Goodrich [5] identified

ebenum populations through most of the Cumberland River drainage, from

“Cumberland River above the falls” through “Smith’s Shoals, Pulaski County,

Kentucky” west beyond Nashville to “springs and small streams” in Dickson

County, Tennessee. Could all these populations that Goodrich called "Goniobasis ebenum" be pale, triangular, robustly-shelled P.

simplex? Stay tuned.

Notes

[1] The best entry into this literature would be to purchase

FWGNA Volume 3 [html] and read pages 1 – 10 and 93 – 99. Or you could click through it piecemeal:

- The Legacy of Calvin Goodrich [23Jan07]

- Goodrichian Taxon Shift [20Feb07]

- Elimia livescens and Lithasia obovata are Pleurocera semicarinata [11July14]

[2] Goodrich, C. (1934) Studies of the gastropod family

Pleuroceridae - I. Occasional Papers of the Museum of Zoology, University of

Michigan 286:1 - 17.

[3] This is actually a bit frustrating. Looking back on Goodrich’s body of work,

there is almost never anything quotable – some “Aha moment” where the fullness

of his vision is revealed. Like Charles

Darwin.

[4] Dillon, R. T., S. J. Jacquemin & M. Pyron (2013)

Cryptic phenotypic plasticity in populations of the freshwater prosobranch

snail, Pleurocera canaliculata.

Hydrobiologia 709: 117-127. [pdf] For more, see:

- Pleurocera acuta is Pleurocera canaliculata [2June13]

- Pleurocera canaliculata and the process of scientific discovery [18June13]

[6] This is a difficult work to cite. J. B. Burch's North American Freshwater

Snails was published in three different ways.

It was initially commissioned as an identification manual by the US EPA

and published by the agency in 1982. It

was also serially published in the journal Walkerana (1980, 1982, 1988) and

finally as stand-alone volume in 1989 (Malacological Publications, Hamburg,

MI).

[7] Minton, R.L. & C. Lydeard (2003) Phylogeny, taxonomy, genetics, and global

heritage ranks of an imperiled, freshwater snail genus Lithasia

(Pleuroceridae). Molecular Ecology 12:

75 – 87.

[8] The best entry to this complex and long-running theme

would be to read FWGNA Volume 2 [html] in its entirety.

Or for a quick lick at the problem, see my essays:

[10] Dillon, R. T. (2014) Cryptic phenotypic plasticity in

populations of the North American freshwater gastropod, Pleurocera

semicarinata. Zoological Studies 53:31.

[pdf] For more, see:

- Elimia livescens and Lithasia obovata are Pleurocera semicarinata [11July14]

[12] I explored the complex relationship between Pleurocera

simplex and P. gabbiana in East Tennessee in a series of three blog posts in 2016:

- The cryptic Pleurocera of Maryville [13Sept16]

- The fat simplex of Maryville matches type [14Oct16]

- One Goodrich missed: The skinny simplex of Maryville is Pleurocera gabbiana [14Nov16]

- CPP Diary: Yankees at The Gap [4Aug19]

No comments:

Post a Comment