Editor’s Note – This essay was subsequently published as: Dillon, R.T., Jr. (2023b) The Union in Tennessee! For lithoglyphid hydrobioids, that is. Pp 289 – 298 in The Freshwater Gastropods of North America Volume 6, Yankees at The Gap, and Other Essays. FWGNA Project, Charleston, SC.

In last month’s episode [11July23], we marched south from Tennessee into Alabama with Gen. Ormsby Mitchel, the First Michigan Engineers and Mechanics Regiment, and Dr. W. H. DeCamp. Capturing Huntsville on the morning of April 10, 1862, Mitchel’s forces moved rapidly both East and West to secure the vital Memphis & Charleston Railroad, by the end of the summer controlling 100 miles of riverbank on the north side of the Tennessee River. And somewhere in the vicinity of Huntsville, sometime during that long and exciting summer of 1862, Dr. William Henry DeCamp, Surgeon US Army, collected a small sample of small lithoglyphid hydrobioids that turned out to be the first Somatogyrus described from the drainage of The Tennessee River, Somatogyrus currierianus (Lea 1863) [1, 2].

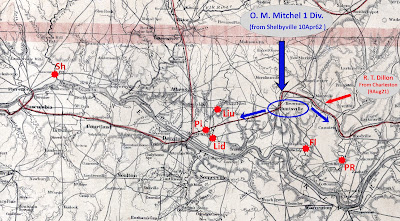

|

| North Alabama campaign [3] |

Last month we also reviewed what is known about the distribution of Somatogyrus elsewhere throughout the Tennessee drainage, both historic and modern. East Tennessee populations have typically been identified with Tryon’s (1865) nomina S. parvulus and S. aureus [4], the former name prevailing in the tributary rivers above Knoxville, the latter further downstream in Knoxville and vicinity. The Hiwassee hosts a well-documented population of Somatogyrus apparently trans-Appalachian in origin, and the little snails also pop up occasionally in TN-DEC macrobenthic samples collected from Chickamauga Creek near Chattanooga as well.

Middle Tennessee populations are less well-known, and if identified at all, are usually assigned the name Somatogyrus depressa, which Tryon (1862) used to describe populations in the Mississippi River at Davenport, Iowa [5]. These include a large population inhabiting the Duck River and a small population in the Harpeth River, a tributary of The Cumberland west of Nashville [6].

Between the East Tennessee populations identified as S. parvulus/aureus and the Middle Tennessee populations identified as S. depressa are Dr. W. H. DeCamp’s old stomping grounds in North Alabama. And last month we concluded that the key to understanding the entire, far-flung Somatogyrus fauna of the Tennessee River system is to understand that little sample of little snails Dr. DeCamp collected at “Huntsville” in 1862, sent to Isaac Lea and described as currieriana the following year [1]. Can Dr. DeCamp’s type population be found again?

That question weighed heavily on my mind as I tipped my hat to the Missus and boarded a westbound train for Alabama in August of 2021 [7]. The Huntsville Somatogyrus problem seemed closely analogous to that with which I had wrestled in the spring of 2020, searching for the type population of Melania perstriata, also described by Isaac Lea from Huntsville but in 1853, before the war [15Apr20]. The field notebook under my arm bulged with many water-stained pages of observations about the malacologically rich area toward which the Memphis & Charleston Railroad was bearing me that morning.

The city of Huntsville, I knew, had built up around a lovely, high-volume spring that was almost certainly the type locality of Melania perstriata, and which was quite likely the type locality of S. currierianus as well. But I was also aware that in modern times the spring and its run have been channeled in concrete bulkheads through a formal midtown park and rendered essentially devoid of macrobenthos. I didn’t see any Somatogyrus there in 2020, when I wasn’t seeing any Pleurocera (“Melania”) perstriata.What to do? It seemed to me that my best option would be to draw a series of concentric circles on my map around the Big Spring of Huntsville and try to find the Somatogyrus population next-closest. So, upon arrival at the Huntsville Depot the next morning, I brushed the cinders from my frock coat, hired a mule-drawn hack at the livery, and set off down the Cottonville Pike for the Flint River about 10 miles distant. This, I knew from experience, was the first body of water my mules would kick into substantial enough to host a population of Somatogyrus, travelling east. And soon a second challenge, beyond the 150 years of landscape evolution boggling my eyes as we clip-clopped by the Starbucks, presented itself.

The Flint River Somatogyrus population is weird looking. I figured a typical specimen in the Cherrytree montage I published in my [3Nov22] essay on Marstonia pachyta and figured a life-sized image of that same specimen again last month [11July23], and I’m going to show you a third time this month, marked Fl in the figure below. The Flint River population seems to reach adulthood at an exceptionally small size, no more than maybe 2-3 mm shell length. The shells they bear are also unusually light and – here’s the big shocker – typically show at least a little bit of umbilicus. That’s right. Flint River Somatogyrus look like Clappia.

I also figured the type of Lea’s S. currierianus last month, and I apologize about the quality of that image; the original picture was only about 5 mm in the monograph. But Lea’s figure showed a much more robustly shelled snail, no umbilicus in evidence, as is typical for the genus. Standing ankle-deep in the Flint River in the summer of 2021, holding the reins of a brace of wet mules in my left hand, I simply could not bring myself to designate the weird-looking little Somatogyrus crawling around at the bottom of the sawed-off trashcan I was holding in my right, as topotypic currierianus.

So, I re-mounted my asinine conveyance, and with a light touch of the whip continued eastward another 10 dusty miles or so beyond the Flint, to the sparkling waters of the Paint Rock River. And there I found a somewhat larger-bodied and heavier-shelled population of Somatogyrus, a typical specimen from which is labeled PR above. The Paint Rock population bears shells that are not umbilicate, and look fairly typical for the genus, and I thought at the time, might suit as modern topotypes. Storing a sample in my watch pocket, I turned my wagon back into the setting sun, and returned to Huntsville for the night.

The next morning, I bought a fresh ticket at the station and boarded a westbound for Decatur and Tuscumbia. And I resolved, as I did, to jump off at the first trestle [8], crossing the Limestone Creek about 15 miles west of the city. She was making 30 miles an hour as we approached the bridge, but the drop was no more than 12 -15 feet, so I landed with the loss of no more than my hat, and vision in my left eye.

The shells borne by the Somatogyrus I plucked from Limestone Creek looked fairly typical, at least in the downstream precincts of Mooresville, at the railroad crossing. See figure Lid above. But as I made my way upstream, a new and intriguing phenomenon unfolded before my eyes. The shells of the Limestone Creek Somatogyrus population began to open an umbilicus. The photo below compares a shell collected downstream, 1 mile NE of Mooresville (Lid), to a shell collected about 12 miles upstream, at Capshaw (Liu). Although the former is quite typical for Somatogyrus populations throughout the Tennessee drainage, the latter would conventionally be identified as Clappia.

And then it dawned upon me that I had seen this same phenomenon in the Powell River ten years previous – a Clappia population upstream blending into a Somatogyrus population downstream [9]. Both upstream populations seem to reach maturity at a smaller size, bear lighter shells, and prefer a substrate of woody debris on the margins. The downstream populations are larger, more robustly shelled, and inhabit rocks midstream. The parallel nature of this phenomenon, as it apparently manifests itself in both East Tennessee and North Alabama, suggested to me cryptic phenotypic plasticity of a high and aggravated nature.

All these thoughts tumbled through my mind as I walked the dusty road west toward Piney Creek, no more than a mile beyond Mooresville. And what I found in Piney Creek reminded me very much of what I had seen in the Flint River on the previous day. The Somatogyrus population of Piney Creek was exceptionally small-bodied, lightly shelled, and umbilicate, animals reaching adulthood not much more than 2 mm shell length, as depicted in Figure Pi above.

That evening I camped under the Decatur bridge, cooked a cup of chicory coffee in a tin can, and watched the Tennessee River flow by. Actually, the river didn’t flow any more than I did. Although this stretch of river would have been wild and free in 1862, the TVA closed Wheeler Dam about 30 miles downstream in 1936, backing the Tennessee River up almost 60 miles to Huntsville. And all that met my eye that evening at the Decatur Bridge was slackwater swamp.

How many molluscan lives were lost as those flat, scummy waters inundated the historic Muscle Shoals between Florence and Decatur, I wondered to myself, as the sun set. How many millions of unionid mussels, how many billions of pleurocerid snails? Throughout the nineteenth century and into the twentieth, scores of Melania, Anculosa, Leptoxis, Pleurocera, Trypanostoma, Goniobasis, Lithasia, Angitrema, Strephobasis, and Eurycaelon were described and re-described from the rivers and streams around Muscle Shoals [10]. The pleurocerid populations inhabiting the roiling waters of that mighty river, bearing heavier, more robust shells, were typically assigned Latin nomina different from more lightly shelled populations inhabiting the gentler tributaries.

The Pleurocera canaliculata population inhabiting the main Tennessee River here at Decatur, I knew, extends up nearby Limestone Creek, where they were described as Melania pyrenella by Conrad in 1834. Historic nomina such as Conrad’s pyrenella, although now relegated to synonymy [11], nevertheless have demonstrable utility to describe morphological forms not apparently correlated with reproductive isolation, possibly ecophenotypic in origin. We have suggested that such nomina, especially those around which some published literature has subsequently developed, be preserved at the subspecific level by virtue of their indexing function.

Similarly. In 1906 Bryant Walker described seven species of Somatogyrus from the Muscle Shoals area, all of which bore robust shells, apparently adapted to large rivers with strong current [12]. Figure Sh above shows a typical specimen of Walker’s S. tennesseensis from the Florida State Museum (cat. 83116), collected at “Shoals Creek near mouth with Tennessee River” date unknown. That big-river shell morphology seems to match the image of Lea’s currierianus (see last month) better than any of the populations inhabiting the smaller tributary waters today. But alas, the Somatogyrus of Muscle Shoals were buried under the slackwater with the unionids and the pleurocerids in 1936. Gone With The Swamp.Then by analogy with the better studied pleurocerids, we suggest that the following nomina are junior synonyms of Somatogyrus currierianus (Lea 1863): aureus Tryon 1865, excavatus Walker 1906, humerosus Walker 1906, parvulus Tryon 1865, quadratus Walker 1906, sargenti Pilsbry 1895, strengi Pilsbry & Walker 1906, substriatus Walker 1906, and tennesseensis Walker 1906 [4, 12, 14].

And extending the analogy further. The evidence reviewed above suggests that the populations described by Bryant Walker in 1904 as Somatogyrus umbilicata [15], separated by him into a new genus Clappia in 1909 [16], are lightly shelled upstream variants of Somatogyrus currierianus. We therefore propose that Walker’s nomen umbilicata be lowered to subspecific status under Lea’s S. currierianus.

And in conclusion, we take this opportunity to remind our readership once again that the FWGNA has adopted the definition of the word “subspecies” standard since the Modern Synthesis, “populations of the same species in different geographic locations, with one or more distinguishing traits” [17]. Although there certainly may be some heritable basis for the umbilicus demonstrated by the shells of some small river Somatogyrus populations, and indeed for all the remarkable shell variety of all the remarkable freshwater malacofauna of North Alabama, ecophenotypic origins are at least equally likely.

Notes

[1] Lea, I (1863) Descriptions of fourteen new species of Melanidae and one Paludina. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 4: 154 – 156.

[2] Lea, I (1866) New Unionidae, Melanidae, etc., chiefly of the United States. Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia Series 2, 6: 113 – 187.

[3] This is a small detail from a map of Alabama and Mississippi published by the United States Coast Survey in 1865. Retrieved from the Library of Congress here: https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3980.cw0259500/

I added the colored marks and notes.

[4] Tryon, G. W. Jr. (1865) Descriptions of new species of Amnicola, Pomatiopsis, Somatogyrus, Gabbia, Hydrobia and Rissoa. American Journal of Conchology 1: 219-222, pl 22, figs 5-13.

[5] Tryon, G. W. (1862) Notes on American fresh water shells, with descriptions of two new species. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 14: 451 – 452. I really think that Somatogyrus populations of the main Mississippi River are today best identified as Somatogyrus integra (Say 1829).

[6] Here’s a download of all 2,152 the Somatogyrus occurrences in the GBIF, as of 17Oct22: GBIF.org (17 October 2022) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.nv3tjh

[7] No, I drove I-20 to I-75 like everybody else these days and spent two hours in the Atlanta traffic.

[8] Actually, a westbound train from Huntsville will cross Indian Ck, Bradley Ck, and Beaverdam Ck before arriving at Limestone Ck. None of these smaller streams seems to host a Somatogyrus population today.

[9] For a review of Bryant Walker’s contributions to our understanding of the hydrobioid genera Somatogyrus and Clappia, together with my own personal observations from East Tennessee on these enigmatic taxa, see:

[10] The actual count of pleurocerid species inhabiting the waters of North Alabama today totals ten: Leptoxis praerosa, L. crassa, Lithasia armigera, L. verrucosa, Pleurocera canaliculata (2ssp), P. clavaeformis (2 ssp.), P. laqueata, P. nassula, P. simplex, P. troostiana (3 ssp).

[11] Dillon, R. T., S. J. Jacquemin & M. Pyron (2013) Cryptic phenotypic plasticity in populations of the freshwater prosobranch snail, Pleurocera canaliculata. Hydrobiologia 709: 117-127. [PDF] For a discussion of these important results, see:

- Pleurocera acuta is Pleurocera canaliculata [3June13]

- Pleurocera canaliculata and the process of scientific discovery [18June13]

[12] Walker. B. (1906) New and little known species of Amnicolidae. Nautilus 19: 97-100, 114-117. In this paper Walker (solo) described six Somatogyrus from Shoal Creek and the main Tennessee River around Florence, Alabama: substriatus, humerosus, quadratus, excavatus, tennesseenis, and biangulatus [13]. He also described strengi from the same area, which he credited to “Pilsbry & Walker.”

[13] I think that the populations Walker described as Somatogyrus biangulatus in 1906 may indeed have been biologically distinct, and now extinct.

[14] Pilsbry, H.A. (1895) New forms of American shells. Nautilus 8(9): 102.

[15] Walker, B. (1904) New species of Somatogyrus. Nautilus 17: 133 - 142.

[16] Walker, B. (1909) New Amnicolidae from Alabama. Nautilus 22: 85 - 90.

[17] For an elaboration of the concept, see: