Review: Whelan, N. V., Johnson, P. D., Garner, J. T., Garrison, N. L., & Strong, E. E. (2022). Prodigious polyphyly in Pleuroceridae (Gastropoda: Cerithioidea). Bulletin of the Society of Systematic Biologists, 1(2). https://doi.org/10.18061/bssb.v1i2.8419

Although I myself have never harbored any aspiration to reconstruct a phylogenetic tree [1], I can understand the intellectual appeal of the fancy new whole-genome technique called “Anchored Hybrid Enrichment” (AHE) to the not-insubstantial fraction of my professional colleagues who feel differently. AHE reminds me of an obsolete technique called single-copy DNA hybridization, which I greatly admired in the 1980s, where pioneering researchers like Sibley & Ahlquist [3] extracted the entire genomic DNA of bird #1 and bird #2, chopped it, melted it to single strands, then cooled it to the temperature that repetitive DNA would reanneal and stick in a hydroxyapatite column, eluting just the single-copy DNA out the bottom. They would then mark the single-copy DNA of bird #1 with P-32, mix it with a large excess of single-copy DNA of bird #2, melt the mixture again, and gradually elute the mixture back through the hydroxyapatite, cooling slowly, to estimate the similarity of bird #1 and bird #2 across all their single-copy genes together.

The terrible flaw in the technique of single-copy DNA hybridization, as practiced in the 1980s, was that it yielded a matrix of overall genetic similarities across pairs in a set of study individuals, committing the mortal sin of being phenetic. The Sibley & Ahlquist hypothesis for the evolution of birds disappeared into the footnotes many years ago [4]. If only there were a technique to do exactly the same thing with a bazillion single-character nucleotide differences, that could be sanctioned as cladistic, am I right?

|

| Anchored Hybrid Enrichment [6] |

In recent years, the coupling of mind-numbing computer power with high-throughput DNA sequencing technology has spawned a variety of whole-genome phylogenetic techniques (“phylogenomics”) that harken back to the days of Sibley & Ahlquist. As the name implies, anchored hybrid enrichment [5] depends on the development of “anchors,” DNA probes to target and enrich highly conserved regions within the whole genomes of a set of organisms under study. The idea is that the regions flanking such probe areas – not the probe areas themselves – are likely to be less conserved, and hence have some utility in phylogenetic construction.

So, in June of 2022 a research group of our own colleagues, headed by Nathan Whelan of Auburn University, published the first application of AHE technology to the reconstruction of a molluscan phylogeny, as far as I know [7]. And it was to the North American Pleuroceridae that their attention was drawn.

Bless their hearts, all five members of the team. I mean that sincerely. A lot of what I am getting ready to write over the next couple essays will be critical. Such is science. But I do not mean to minimize their innovative spirit, their commendable effort, or their motives, which were the highest. We really do need a lot more research like this, and a lot more researchers like Nathan Whelan and his colleagues to do it. Better understanding of the basic evolutionary biology of their living, breathing study animals, before chopping them into massively-parallel chum and high-through-putting them off the stern of a next-generation sauceboat, is all that is wanted. That, plus some nod toward calibration, for a change. Oh, and a passing familiarity with the recently published scientific literature on the subject matter would have been really helpful, too.

OK, first. Regarding the generation of the AHE probes (or “baits”). Rather than extracting total genomic DNA, the Whelan team extracted mRNA from five pleurocerid species “chosen to maximize phylogenetic diversity,” which we will call “Probe Species A – E.” Those five mRNA samples were mailed off to Rockville, Maryland, for the generation of transcriptomes, that subset of the genome actually doing something. I like that. That’s a good way to factor out junk DNA before stepping up to the starting block. Ultimately, our colleagues identified 742 baits “present in at least 4 of 5 pleurocerid transcriptomes and larger than 120 bp in length.”

|

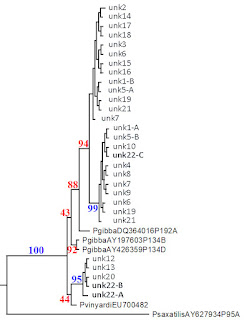

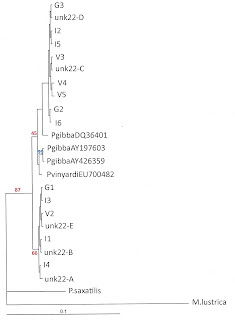

| Figure 4 of Whelan et al [7] |

These 742 baits were trolled through a school of 192 sharks – and by sharks, I mean the whole genomes of individual pleurocerid snails – representing 92 putative species, with two rays – and by rays, I mean the whole genomes of two individual Juga plicifera from the west coast – to serve as an outgroup. And I do want to commend the Whelan group for the care and completeness they took in documenting their study sample. The shells from each of those 194 individual snails were numbered, photographed, and deposited in the USNM. And complete locality data for all 194 snails were made available in tabular form from the journal website, as well as a big folder of 194 jpeg images. We who sail in your chum salute you, colleagues.

One could only wish that the actual fishing trip hadn’t turned so fraught with peril. Total genomic DNA was extracted from those 194 individuals and sent off to Gainesville, Florida, for AHE library prep and sequencing. Three different datasets were generated by this process, under three different assumptions (masked, probe, and full), and trees generated using two different algorithms (ML and ASTRAL). The ASTRAL method also involved two assumptions (TaxMap yes or no), yielding N = 9 gigantic, eye-assaulting, headache-inducing phylogenomic trees. Eight of these trees were consigned to the Supplementary Material. And the tree that Whelan and colleagues liked best, probe + ASTRAL + TaxMap, was published in the journal article, in circular format, as though we evolutionary biologists were birds looking down upon a tree of sharks, which are actually snails, which the most spectacular mixture of metaphor I have muddled in recent memory.

|

But when I first laid eyes on Nathan Whelan’s favorite phylogenomic tree for the gastropod family we both so obviously love, I had to smile. I honestly cannot remember when the result of an evolutionary study gave me more pleasure.

As (I imagine) my loyal readership will remember, in 2014 I published a paper in Zoological Studies [8] extending my research on cryptic phenotypic plasticity to the widespread set of pleurocerid populations variously identified using the specific nomina livescens, semicarinata, and obovata, variously allocated to the genera Pleurocera or Goniobasis or Elimia or Lithasia. I showed that all of these populations, including those traditionally identified as Lithasia obovata and Elimia semicarinata, are conspecific, their evolutionary relationship obscured by extreme phenotypic plasticity of shell. See my blog post of [11July14] for a complete review.

The power of a scientific hypothesis is its ability to predict, to yield new information, to give something back that was not put into it. That Nathan Whelan and his team successfully recovered the close evolutionary relationship between N = 2 snails they identified as “Elimia semicarinata” from the Middle Fork Vermillion River in eastern Illinois and N = 2 snails they identified as “Lithasia obovata” from the Ohio River between Indiana and Kentucky is a demonstration that this new AHE technique can have great power.

Yes, the assumptions that brought us the Whelan et al. phylogenomic tree are as manifold and diverse as shells on the beach, and yes, the opportunities for experimental error were as countably-infinite as the nucleotides. And yes, the human error introduced into the Whelan study most certainly did reach embarrassing levels at times, as we shall see.

But hiding in the abstract splatter of drab shells and gaily-colored tangle of branches above – yellow Elimia, blue Pleurocera, green Lithasia and purple Leptoxis – is genuinely important insight regarding the evolution of the North American pleurocerid snails. There is sweet music to be heard in that noise, if one brings an understanding of the biology of those wonderful organisms to the concert. Which we will do, next time.

Notes:

[1] By

way of full disclosure, my colleagues and I did reconstruct a species tree for

the Physidae in 2011 [2], which we compared to a gene tree previously

published. But please note that every

other treelike diagram I have ever published in my entire career has been a

nearest-neighbor or cluster analysis, intended to represent genetic

similarities only. Which I have always

oriented sideways, to look as little like a tree as possible.

[2]

Dillon, R. T., A. R. Wethington, and C. Lydeard (2011) The evolution of

reproductive isolation in a simultaneous hermaphrodite, the freshwater snail

Physa. BMC Evolutionary Biology 11:144. [pdf]

[3]

Sibley, C.G. & J.E. Ahlquist (1990) Phylogeny and Classification of

birds. Yale University Press, New Haven.

[4] Prum

RO, Berv JS, Dornburg A, Field DJ, Townsend JP, Lemmon EM, and Lemmon AR

(2015). A comprehensive phylogeny of birds (Aves) using targeted

next-generation DNA sequencing. Nature 526(7574):569-73. doi:

10.1038/nature15697.

[5] For

more about Anchored Hybrid Enrichment, see:

- Lemmon, AR, SA Emme, and EM Lemmon (2012) Anchored hybrid enrichment for massively high-throughput phylogenomics. Systematic Biology 61: 727 – 744.

- Lemmon, E.M., and A.R. Lemmon (2013) High-throughput genomic data in systematics and phylogenetics. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 44: 99 – 121.

- Jones, M.R. and J.M. Good (2016) Targeted capture in evolutionary and ecological genomics. Molecular Ecology 25: 185 – 202.

[6] This graphical summary is heavily modified from an original illustration by Bas Blankevoort in

Gravendeel,

B., D. Bogarin, A. Dirks-Mulder, R. Kusuma Wati, and D. Pramanik (2018) The

orchid genomic toolkit. Cah. Soc. Fr.

Orch. 9.

[7]

Whelan, N. V., Johnson, P. D., Garner, J. T., Garrison, N. L., & Strong, E.

E. (2022). Prodigious polyphyly in Pleuroceridae (Gastropoda: Cerithioidea).

Bulletin of the Society of Systematic Biologists, 1(2).

https://doi.org/10.18061/bssb.v1i2.8419

[8]

Dillon, R. T., Jr. (2014) Cryptic

phenotypic plasticity in populations of the North American freshwater

gastropod, Pleurocera semicarinata.

Zoological Studies 53:31. [pdf]. For a review, see:

- Elimia livescens and Lithasia obovata are Pleurocera semicarinata [11July14]