Editor’s Notes - We have always tried to avoid excessively technical posts on the FWGNA blog. I typically publish formal research results elsewhere first and subsequently refer to those results here in a more casual tone. Two of the three essays I have posted in recent months about the Lithasia of the Duck River [7Dec21] and [4Jan22] were, for example, preceded by brief, technical notes published in Ellipsaria (the newsletter of the Freshwater Mollusk Conservation Society) in 2020.

The post that follows, however, is technical. Its publication was suppressed by FMCS Newsletter editor Dr. John Jenkinson because one of our mutual colleagues on the FMCS Board [1] called to Dr. Jenkinson’s attention that Ellipsaria content is being indexed by Google Scholar, and hence that the hypotheses I have proposed below [2] might fall upon naïve and uncritical eyes. This essay was ultimately published as: Dillon, R.T., Jr. (2023b) No reproductive isolation between Lithasia populations of the duttoniana and jayana forms in the Duck River, Tennessee. Pp 175 – 182 in The Freshwater Gastropods of North America Volume 6, Yankees at The Gap, and Other Essays. FWGNA Project, Charleston, SC

The taxonomic history of the pleurocerid genus Lithasia (Haldeman 1840) is a long and complicated one. Goodrich (1940) recognized 16 taxa of Lithasia with smooth shells, 3 with tuberculate shells, and 5 taxa bearing shells with spines or acute protuberances. This last category comprised Lithasia duttoniana, described by Lea (1841) from the Duck River, L. jayana, also described by Lea (1841) from Caney Fork (of the Cumberland), and three subspecies of L. armigera, described by Say (1821) from the Ohio River.

Goodrich considered both Lithasia jayana, a heavily-shelled species bearing two rows of spines, and Lithasia duttoniana, a more lightly-shelled species typically bearing (at most) a single row of small protuberances, endemic to the rivers from which they were described. Lithasia armigera, as understood by Goodrich, ranged from the lower Ohio and Wabash Rivers through most of the Cumberland River and much of the Tennessee River as well.

In an unpublished report to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Davis (1974) suggested that Lithasia be subsumed under the genus Io of Isaac Lea (1831). Davis then went on to recognize three smooth-shelled taxa in the Duck River, which do not concern us here, and two spiny taxa, which he identified as Io armigera duttoniana and Io armigera jayana. After a period of comment and revision, Davis’ spiny taxa were offered for review under the Endangered Species Act in the Federal Register (May 22, 1984) as Lithasia duttoniana and Lithasia jayana.

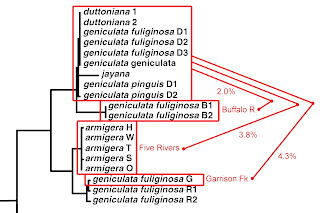

Minton & Lydeard (2003) surveyed mitochondrial CO1 sequence variation in Lithasia populations from the Duck River and many other river systems of the American southeast. The 4 unique sequences they obtained from 19 Duck River snails (1 jayana, 4 duttoniana, and 14 of smooth-shelled taxa, in 9 Genebank submissions) did not resolve into consistent clades. Thus Minton & Lydeard synonymized all Duck River populations, bearing both smooth and spiny shells, under a single smooth-shelled nomen, L. geniculata (Haldeman 1840).

Dillon (2020 b, c) has recently reported, however, a survey of allozyme variation in Duck River Lithasia confirming Goodrich’s (1940) hypothesis that populations of the spiny duttoniana form are reproductively isolated from the more smooth-shelled form, which Dillon followed Goodrich in identifying as Lithasia geniculata.

The large and diverse samples of Lithasia analyzed by Dillon (2020 b, c) were collected incidentally during a survey of the Duck River mussel fauna conducted by Ahlstedt et al. (2017). In addition to populations bearing shells of the (smooth-shelled) geniculata form and the lighter, single-spined duttoniana form, the collections made by Ahlstedt and colleagues at two of their most downstream sites also contained Lithasia bearing shells of the heavy, doubly-spined jayana form. Here I compare those doubly-spined jayana samples to sympatric samples of the lightly-shelled duttoniana form using gene frequencies three allozyme-encoding loci.

|

| Fig. 1. The Duck River, showing sample sites. |

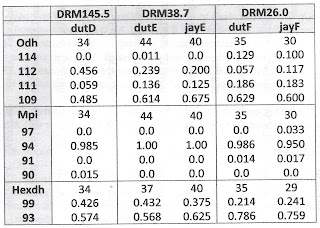

Sample sites and example shells are shown in Figure 1 above. (The shell length of dutF is 24.6 mm; the other shells are to scale.) At their most downstream site, site F, Ahlstedt and colleagues collected 35 Lithasia of the duttoniana form (dutF) and 30 of the jayana form (jayF). This site, the Watered Hollow Boat launch at Duck River Mile 26.0 (35.9322, -87.7475), was the point at which Minton & Lydeard (2003) collected their sample of L. jayana for mtDNA sequencing. Upstream at Wright Bend Site E (TNC110, DRM 38.7, 35.8267, -87.6657), Ahlstedt collected 44 Lithasia of the duttoniana form (dutE) and 40 of the jayana form (jayE).

Lithasia bearing shells of the jayana morphology become increasingly rare further upstream and are not effectively collectable above Duck River mile 60. But populations of the more lightly-shelled duttoniana type extend as far upstream as DRM 186. Gene frequencies in duttoniana population dutD, collected from the Fountain Creek confluence at DRM 145.5 (TNC 94, 35.5695, -86.9682), are included here for comparison.

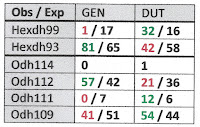

Table 1 below shows that no significant allele frequency differences were apparent between samples bearing shells of the duttoniana and jayana forms at either site where they co-occurred. This was true for the Odh locus (chi-square = 0.688, 2 df at site E, chi-square = 1.62, 3 df at site F), the Mpi locus (Fisher’s p = 0.334 at site F) and the Hexdh locus (Fisher’s p = 0.513 at site E, p = 0.832 at site F). Judging by Nei (1978) genetic distance, sample jayE was more genetically similar to sample dutE (D = 0.050), and sample jayF was more similar to dutF (D = 0.080) than jayE was to jayF (D = 0.161) or dutE to dutF (D = 0.164).

Gene frequency differences were very significant longitudinally, however, at two of the three loci examined. Combining the 44 + 40 = 84 samples from site E (DRM 38.7) and comparing to the 35 + 30 = 65 samples from site F (DRM 26.0), chi-square = 26.2 (3 df, p < 0.00001) at the Odh locus and chi-square = 9.91 (1 df, p = 0.002) at the Hexdh locus. The dutD sample collected upstream at DRM 145.5 also differed significantly at the Odh locus from the combined site E sample (chi-square = 7.84, 2df, p = 0.02).

|

| Tab 1. Gene frequencies at three loci in five samples of Lithasia. |

These results reflect no evidence of reproductive isolation between Lithasia bearing the duttoniana shell morphology and those bearing the jayana shell morphology. The genetic evidence is strong, however, for isolation by distance among the spiny Lithasia populations down this length of river, similar in magnitude to that documented by Whelan et al. (2019) in Alabama Leptoxis, and Dillon (2020a) in North Carolina Pleurocera.

The similarity between these results and those previously published by Dillon (2020b) for the smooth-shelled Lithasia of the Duck River is striking. Dillon confirmed the hypothesis of Goodrich (1934) that the shells borne by Duck River Lithasia geniculata also become more robust when sampled in a downstream direction, adding bumpy shoulders to the point that 19th-century authorities recognized two additional species, L. fuliginosa and L. pinguis. Here an identical phenomenon is documented in the spiny Lithasia, populations identified by Goodrich as Lithasia duttoniana developing such robust and heavy shell spines downstream that some authorities have recognized a second species, L. jayana.

Given such levels of shell variability, neither nominal Lithasia duttoniana (Lea 1841) nor Lithasia jayana (Lea 1841) can be distinguished at the specific level from the much more broadly-distributed Lithasia armigera (Say 1821). The suggestion of Davis (1974) that both of Lea’s 1841 nomina be lowered to subspecific status under Say’s L. armigera would seem to have substantial merit.

References

Ahlstedt, S. A., J. R. Powell, R. S. Butler, M. T. Fagg, D. W. Hubbs, S. F. Novak, S. R. Palmer and P. D. Johnson. 2017. Historical and current examination of freshwater mussels (Bivalvia: Margaritiferidae: Unionidae) in the Duck River basin Tennessee, USA. Malacological Review 45:1-163.

Davis, G.M. 1974. Report on the rare and endangered status of a selected number of freshwater Gastropoda from southeastern U.S.A. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Washington, DC. 51 p.

Dillon, R. T., Jr. 1982. The correlates of divergence in isolated populations of the freshwater snail, Goniobasis proxima (Say). Ph.D. Dissertation, The University of Pennsylvania.

Dillon, R. T., Jr. 1985. Correspondence between the buffer

systems suitable for electrophoretic resolution of bivalve and gastropod

isozymes. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology 82B: 643-645. [pdf]

Dillon, R. T., Jr. 1992. Electrophoresis IV, nuts and bolts.

World Aquaculture 23(2):48-51.

Dillon, R. T., Jr. 2020a. Fine scale genetic variation in a

population of freshwater snails. Ellipsaria 22(1): 24-25. [pdf]

Dillon, R. T., Jr. 2020b. Population genetic survey of

Lithasia geniculata in the Duck River, Tennessee. Ellipsaria 22(2):19 – 21. [pdf]

Dillon, R. T., Jr. 2020c. Reproductive isolation between

Lithasia populations of the geniculata and duttoniana forms in the Duck River,

Tennessee. Ellipsaria 22(3): 6 – 8. [pdf]

Goodrich, C. 1934. Studies of the gastropod family

Pleuroceridae - I. Occasional Papers of the Museum of Zoology, University of

Michigan 286:1-17.

Goodrich, C. 1940. The Pleuroceridae of the Ohio River

drainage system. Occasional Papers of the Museum of Zoology, University of

Michigan 417:1 - 21.

Minton, R. L. and C. Lydeard. 2003. Phylogeny, taxonomy,

genetics, and global heritage ranks of an imperiled, freshwater snail genus

Lithasia (Pleuroceridae). Molecular Ecology 12:75-87.

Nei, M. 1978 Estimation of average heterozygosity and

genetic distance from a small number of individuals. Genetics 89:583–590.

Whelan, N. V, M. P. Galaska, B. N. Sipley, J. M. Weber, P. D. Johnson, K. M. Halanych and B. S. Helms. 2019. Riverscape genetic variation, migration patterns, and morphological variation of the threatened Round Rocksnail, Leptoxis ampla. Molecular Ecology 28:1593-1610.

Notes

[1] Here is the relevant passage from the minutes of the FMCS Board, November 19, 2020:

“Nathan Whelan noticed recently that some Contributed Articles in Ellipsaria are now findable on Google Scholar. This was unexpected for our informal, non-peer-reviewed newsletter. Nathan also recognized that some recent articles in the newsletter include the analysis of data and/or what could be viewed as proposed taxonomic revisions. In a series of emails, monitored and, occasionally, participated in by the Executive Committee, Nathan and Ellipsaria Editor John Jenkinson agreed that articles including data analysis and/or taxonomic revisions should be peer-reviewed and, therefore, are outside of the intended scope and purpose of our newsletter.”

[2] Science is the construction

of testable hypotheses about the natural world.

It is not the handing down of fact.

It appeals to no authority, nor does it merit any. It is independent of context or culture. Whether published in a slick international

journal or a humble newsletter is irrelevant.

The quality of a work of science is dependent only upon the extent to

which the hypothesis proposed matches the natural world, upon rigorous

test. And it stuns me – literally stuns

me – to see how few scientists actually understand any of this.