Editor’s Note: This is the second essay in a fresh series on the Snake River Physa controversy, prompted by the 2021 publication of new genetic data by M. K. Young and colleagues [1]. If this is your first visit to the FWGNA blog, I would suggest that you back up to last month’s post at minimum [14May24]. And if you have a serious interest in the subject, from last month’s essay you can follow links to six previous posts on Physa natricina and the Snake River, 2008 – 2013.

Located 35 miles south of Boise on the Snake River at River Mile (RM) 458, the Swan Falls Dam is something of a museum piece. It was constructed in 1901 by local mining companies as a demonstration of the potential for waterpower to drive industry in a land that was just beginning to assert its potential. That dam and its generating plant were consolidated into the newly incorporated Idaho Power Company, IPC, in 1916.

|

| Swan Falls Dam |

Physa natricina, described in 1988 from the Snake River upstream at RM525 – RM571 [2], was entered onto the federal endangered species list in 1992 [3]. And at that point, alas, IPC found itself in the Physa business, as well as in the power business. IPC biologists initiated a comprehensive Physa survey and monitoring program in 1995, beginning way downstream at the Oregon border (RM 340) extending upstream to the Lower Salmon Falls Dam (RM 573), using a broad range of sampling techniques, including Venturi loop dredging apparatus operated by tethered divers in deeper and more rapid waters. By 2007, over 1,500 Physa specimens had been collected from these 233 miles of river, identified to genus (only) and deposited in the Orma J. Smith Museum of Natural History (ALBRCIDA) in Caldwell, Idaho.

In 2007, our colleagues Christopher Rogers and Amy Wethington examined this gigantic collection of preserved gastropods and compared them, critically and completely, to the type specimens of Physa natricina deposited by Dwight Taylor in connection with his 1988 description [4]. They found no individual snail matching all eight of Taylor’s diagnostic characters completely. Indeed, none of Taylor’s paratypes matched all eight characters of his holotype. Taylor’s “diagnostic characters” were variable. And that variation extended seamlessly from his holotype Physa natricina to merge with the (extremely variable) North American invasive species Physa acuta, which is what the great majority of those 1,500 snails collected between RM 340 and RM 573 between 1995 and 2007 appeared to be.

Rogers and Wethington synonymized Dwight Taylor’s narrowly endemic P. natricina under the cosmopolitan P. acuta, suggesting as they did that the stunted morphology and unusually large body whorl demonstrated by individuals sampled from stones in exposed environments in the middle of the Snake River might be an ecophenotypic response to life in rapid currents.

Our scene now shifts to the Minidoka Dam, way upstream at RM 675, a hundred miles above any place that Dwight Taylor or IPC ever surveyed for Physa. The Minidoka Dam is also a museum piece, built by the brand new US Bureau of Reclamation in 1906 to supply water for irrigation. In 2005 the USBR contracted with a pair of biologists from Montana State University, Kiza Gates and Billie Kerans, “to thoroughly survey the USBR P. natricina recovery area from RM 663-675 and determine if any P. natricina populations or colonies exist” [5]. These surveys, conducted by tethered divers operating Venturi suction dredges, extended through the field seasons of 2006 – 2008.

Gates & Kerans ultimately recovered 274 physids with shell morphology matching the description of Physa natricina in at least some respects, of which roughly 15 were sequenced for two mtDNA genes by two different laboratories. Concatenated, these sequences averaged 17% different from a set of reference Physa acuta fished from GenBank. The gray literature report of Gates & Kerans [5], released in 2010, “confirmed the original description of P. natricina as a distinct species and the existence of a population below Minidoka Dam.”

|

| The Snake River, modified from Fig 3 of Gates et al [6] |

My concern, stated forcefully at a meeting convened by the USBR in Boise in September of 2010 [2Apr13], was that the physids Gates & Kerans were identifying as Physa natricina must be compared to the Snake River acuta-like Physa (“SRALP”) common as cockroaches in the shallows of the river downstream, not to random Physa acuta fished from GenBank, none sampled closer than Wyoming, on the other side of the continental divide. My cries fell on deaf ears [6].

I might also have objected that the physids Gates & Kerans were identifying as “Physa natricina” must also be compared to bona fide Physa natricina sampled from the type range, RM 525 – 571, but I did not realize the significance of that problem until much more recently [14May24]. In retrospect, the Physa that Gates & Kerans did sample below the Minidoka Dam are best referred to as Snake River natricina-like Physa (SRNLP), just as the Physa they did not sample downstream were SRALP.

Setting all such pretty distinctions aside, however, sailing 215 river miles back downstream to the Swan Falls Dam, and picking up the story as told by Idaho Power in a 2011 gray literature report to the FWS [7]:

“Verified specimens of Snake River physa were very rare until recently, when the USBR discovered them in the upper Snake River (Gates and Kerans 2010). These new collections of Snake River Physa prompted IPC to re-evaluate specimens identified as Physidae from samples collected throughout the Middle and Lower Snake River from 1995–2003. John Keebaugh of the Orma J. Smith Museum of Natural History at the College of Idaho in Caldwell, Idaho, identified 51 (live when captured) Snake River Physa from 19,426 specimens identified as Physidae (Keebaugh 2008) (Table 2). These Snake River Physa were collected between Bliss Dam (RM 559.3) downstream to a site near the mouth of the Payette River (RM 367.9). Of the 51 Snake River Physa Keebaugh identified from IPC’s samples, 37 were collected in the (Swan Falls) Action Area (RM344 – RM469).”

The IPC went on to report that anatomical and genetic studies “conducted by Montana State University” had confirmed the Keebaugh identifications. Those genetic results (from the laboratory of Steven Kalinowski) were dubiously transmitted in 2013 [6] and never vouchered. But the bottom line is this. A physid population morphologically indistinguishable from Physa natricina inhabits the rapids downstream from the Swan Falls Dam (RM 458). This is a factual observation, with which all parties, Christopher Rogers, Amy Wethington, John Keebaugh, Gates, Kerans, and (most importantly) the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service will all most certainly concur.

|

| IPC biologists collecting suction dredge samples [8] |

So, on the basis of what would seem to be universal scientific consensus, in 2011 the FWS required IPC to re-apply for its license to operate the Swan Falls Hydroelectric Project. That new license, approved on September 28, 2012, contained an article that required a “snail protection plan focusing on Snake River Physa (Physa natricina),” directly analogous to the study that the US Bureau of Reclamation had undertaken in the tailwaters of the Minidoka Dam seven years earlier. And in 2013 an elaborate five-year plan was approved [9], coauthored by IPC biologists Michael Stephenson [10] and Barry Bean.

But wait. Because all the Physa populations inhabiting the length of the Snake River in Idaho have been the focus of intense legal and regulatory controversy for over 30 years now, exceptional rigor is demanded throughout. And again, I must remind all parties that Dwight Taylor stated in his 1988 description that Physa natricina is “restricted to the Snake River from the vicinity of Bliss to Hammett, Idaho,” generally taken to range from RM 525 – 571. So, the term we coined last month [14May24], “Snake River natricina-like Physa” (SRNLP) is the most appropriate name for both the stunted populations of Physa bearing shells with unusually large body whorls above that range, in the tailwaters of the Minidoka Dam at RM 675, and the stunted populations of Physa bearing shells with unusually large body whorls below that range, in the tailwaters of the Swan Falls Dam at RM 458.

Now moving forward. The dawn of the 2014 field season saw IPC scuba divers, tethered to boats in the roaring Snake River rapids, sampling rocks and cobbles with Venturi power jet suction dredges at five selected sites between RM 400 and RM 445. The total of 105 individual physids ultimately recovered [11] were sent to our good friend Hsiu-Ping Liu at the Metropolitan State University of Denver, who was able to obtain 16S mtDNA sequences from 59 of them [12]. The maximum sequence divergence across the entire set of 59 was just 3.6%. Alas, Hsiu-Ping did not upload her sequences to GenBank or otherwise make them publicly available. But comparing her big Swan Falls sample to an equally large sample of physids fished from GenBank, Hsiu-Ping concluded, “Based on the genetic evidence presented here, Idaho Power samples clustered with P. acuta.” Physa acuta were found.

Idaho Power biologists used an identical tethered-diver technique in the 2015 field season, shifting their five sample sites to some extent, ultimately recovering another 59 individual Physa [13]. In 2016 they experimented with three new approaches, however: drift nets, sturgeon egg mats, and multiplate artificial (“Hester-Dendy”) substrate samplers [15]. Just two Physa were recovered in the nets, and just six in the mats, but promising results with the multiplate samplers [16] suggested a shift to that approach in subsequent years. The 2016 field season was not subsequently counted among the five study years of the contracted project.

|

| SRNLP from Swan Falls tailwaters [14] |

In 2017, 2018, and 2019 IPC biologists deployed a two-part artificial substrate sampler of unusual design: a basket of large cobbles hooked to a multiplate Hester-Dendy apparatus [17]. Thirty such samplers were anchored at various spots in the Snake River rapids downstream of the Swan Falls Dam for two periods of five weeks, for each of the three study years remaining. A total of 132 + 344 + 633 = 1,109 individual physids were recovered from the samplers, a subset of which [19] were sent to the laboratory of a fish guy named Michael K. (Mike) Young, bless his heart, at the USFS Rocky Mountain Research Station for mtDNA sequencing.

Mike and his colleagues [1] ultimately obtained CO1 sequences for 181 physids sampled from the Snake River rapids between RM 420 and RM 449. These sequences were all fully reported and properly vouchered. Eight sequences ultimately matched P. gyrina; let’s set those aside. Then the maximum sequence divergence across the set of 173 that remained was just 4.82% [20]. This is the single largest survey of mtDNA sequence variation ever published for a population of pulmonate snails.

The sequence similarity between the downstream-most sample (SRP051 = OK510624) from RM 420 and the upstream-most sample (SRP182 = OK510755) from RM449 was 100%. Let’s pick the longer of these two identical sequences, OK510624, as typical for SRALP in the Swan Fall tailwaters.

Mike Young is a hard worker and was very patient with me over several weeks of incessant pestering, and he did his best with the tools the Good Lord packed in his tool box, bless his heart. He dumped his block of 173 CO1 sequences from Snake River miles 420 – 449 into a gigantic cauldron of 920 physid CO1 sequences downloaded from every database you can imagine, from everywhere around the world, stirred it twice, and pushed the button on a stupendous, smoke-belching, oil-spewing, gear-grinding, tree-making machine. Shoveled in some coal and gave her a kick.

|

| Cobble Basket / Hester-Dendy sampler [18] |

Carelessly tossed into the bubbling Cauldron O’sequences and piped into the Stupendous Tree-Making Machine was one sequence that actually mattered, AY282589, a CO1 sequence from the type locality of P. acuta in the River Garonne, France. The sequence divergence between OK510624 and AY282589 was 2.4%. Good, thank you Jesus, finally! The Snake River acuta-like Physa, the SRALP, is indeed Physa acuta. At least in the Swan Falls tailwaters, RM 420 – 449. After all these years of Sturm und Drang. Why was that so hard?

In summary. As of 2020, the Idaho Power Company had spent six years and millions of dollars for 105 + 59 + 8 + 132 + 344 + 633 = 1,281 Physa acuta, the world’s most cosmopolitan freshwater gastropod, the cockroach of malacology, invasive on five continents. That is all – that is the complete yield for six years of intense (and sometimes dangerous) effort by a large, well-equipped team of dedicated biologists – with a smattering of P. gyrina easily set aside.

This screaming, flailing 1,281-trash-snail bellyflop will not have been a complete, utter, tragic, waste of time, effort, money and skin if we learn from it. So, pay attention now.

If (1) A physid population morphologically indistinguishable from Physa natricina inhabits the Snake River rapids downstream from the Swan Falls Dam, and if (2) all the physids inhabiting the Snake River rapids downstream from the Swan Falls Dam are Physa acuta, then (3) the evidence at Swan Falls supports the Rogers and Wethington hypothesis that Physa natricina is a junior synonym of Physa acuta. Well, to be as precise and rigorous as I can be, The SRNLP is Physa acuta at RM 420 – 449.

But to be clear. Also dumped into Mike Young’s bubbling Cauldron O’sequences were all nine of the (qualified) CO1 sequences uploaded by Gates, Kerans, and colleagues for the SRNLP sampled from the Minidoka tailwaters 220 miles upstream [6], plus three Minidoka sequences Young and colleagues developed themselves. Those 12 are (indeed) quite strikingly different from the 173 Physa acuta sampled from Swan Falls, and all other sequences in the worldwide Physa database. So, the identity of the SRNLP at RM 675 remains unconfirmed.

Halfway between Swan Falls and Minidoka is the actual type range of bona fide Physa natricina, RM 525 - 571. Does the stunted population of Physa bearing shells with unusually large body whorls in the roaring rapids of the Snake River where it actually matters genetically match the SRNLP population at Minidoka 675, or the P. acuta population at Swan Falls 449? Or? Tune in next time.

Notes

[1] Young, M.K., R. Smith K.L. Pilgrim, and M.K. Schwartz (2021) Molecular species delimitation refines the taxonomy of native and nonnative physinine snails in North America. Scientific Reports 11: 21739. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-01197-3

[2] Taylor, D. W. (1988) New species of Physa (Gastropoda: Hygrophila) from the western United States. Malacological Review 21: 43-79.

[3] US Fish & Wildlife Service (1992). Endangered and threatened wildlife and plants; Determination of endangered or threatened status for five aquatic snails in south central Idaho. 50 CFR Part 17. Federal Register 57(240)59244-57. (December 14, 1992)

[4] Rogers, D. C. & A. R. Wethington (2007) Physa natricina Taylor 1988, junior synonym of Physa acuta Draparnaud, 1805 (Pulmonata: Physidae). Zootaxa 1662: 45-51. For a review, see:

- Red Flags, Water Resources, and Physa natricina [12Mar08]

[5] Gates, K. K., and B. L. Kerans (2010) Snake River Physa, Physa (Haitia) natricina, Survey and Study. Report to the US Bureau of Reclamation under agreement 1425-06FC1S202. 87 pp. For a review of this report, see:

- The Mystery of the SRALP: A bidding… [5Feb13]

- The Mystery of the SRALP: A twofold quest! [1Mar13]

- The Mystery of the SRALP: Dixie Cup showdown! [2Apr13]

[6] Gates, K. K., B. L. Kerans, J. L. Keebaugh, S. K. Kalinowski & N. Vu (2013) Taxonomic identity of the endangered Snake River physa, Physa natricina (Pulmonata: Physidae) combining traditional and molecular techniques. Conserv. Genet. 14: 159-169. [html] For a review, see:

- The Mystery of the SRALP: No Physa acuta were found [2May13]

[7] Bean, B., and M. Stephenson (2011) Swan Falls Biological Assessment for the Snake River Physa. (Swan Falls, FERC Project No. 503). Idaho Power Company, Boise. 30 pp.

[8] “From left to right: Nick Gastelecutto, Michael Stephenson, and Dain Bates.” This is Figure 2 from the IPC report of the 2014 results [11].

[9] Stephenson, M., and B. Bean (2013) Swan Falls Snake River Physa Protection Plan. (Compliance Report, Swan Falls FERC Project No. 503, Article 405) Idaho Power Company, Boise. 78 pp.

[10] Michael Stephenson was at the forefront of the Swan Falls Physa project from its beginnings back in 2011 to the present day, designing the studies, spending long days in the field, and writing the reports. He was tremendously helpful and forthcoming with me in the research for this blog post. On the Altar of Science in the Temple of Public Policy, Michael’s his sacrifice has been heroic. Good job, Old Buddy, and thanks.

[11] Bean, B. (2015) Swan Falls Article 405 Snake River Physa Monitoring Report: 2014 Results. (Compliance Report, Swan Falls FERC Project No. 503) Idaho Power Company, Boise. 32 pp.

[12] Liu, H-P. (2016) Report on taxonomic identity of the Snake River Physa using molecular techniques. Appendix 4 (pp 65 – 73) in IPC report of 2015 results [13].

[13] Bean, B. (2016) Swan Falls article 405 Snake River Physa monitoring report: 2015 results. (Compliance Report, Swan Falls FERC Project No. 503) Idaho Power Company, Boise. 80 pp.

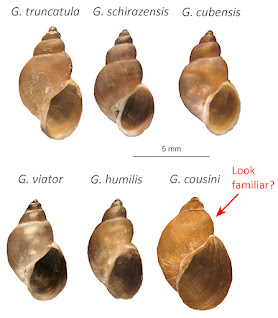

[14] These images come from Appendix 3 of the IPC Report of the 2015 results [13]. Shell lengths (left to right) were given as 1.41 mm, 1.71 mm, 3.64 mm.

[15] Bean, B. (2017) 2016 Snake River Physa Studies in the Swan Falls Reach. (Compliance Report, Swan Falls FERC Project No. 503, Article 405) Idaho Power Company, Boise. 16 pp.

[16] In 2016, IPC biologists actually deployed their experimental multiplate artificial substrate samplers way upstream at RM 674, below the Minidoka Dam, yielding “2 confirmed Physa natricina, as well as one putative Physa natricina,” which were returned to the river.

[17] Bean, B. (2018) Swan Falls Article 405 Snake River Monitoring Report: 2017 Results. (Compliance Report, Swan Falls FERC Project No. 503) Idaho Power Company, Boise. 14 pp.

[18] This is Figure 2 of the IPC Report of the 2017 results [17]. Full caption: “Photo of gravel basket and Hester-Dendy artificial substrate samplers.”

[19] As a rule of thumb, the IPC selected individual physids “with a shell length/width ratio of less than 1.5” to forward on for genetic analysis. I’m not sure where this rule came from.

[20] The team did not formally publish any statistics for their impressive block of 173 sequences. Mike Young communicated the maximum sequence divergence value of 4.82% to me in personal correspondence.