Editor’s Notes – This is the fifth and final installment of my series on the population genetics and systematic relationships of the Duck River Lithasia. If you are interested in the science, you probably ought to review my posts of 7Dec21, 4Jan22, 3Mar22, and 28Mar22 before proceeding. Or you could simply enjoy this essay for what it is, a true tale from the wild west days of American malacology.

This essay was ultimately published as: Dillon, R.T., Jr. (2023b) The ham, the cheese, and Lithasia jayana. Pp 183 – 192 in The Freshwater Gastropods of North America Volume 6, Yankees at The Gap, and Other Essays. FWGNA Project, Charleston, SC

“Well, Ahlstedt, is this jayana or is it not?” That was the punchline of a story told me by my major advisor, Dr. George Davis, shortly after I arrived at the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences in the summer of 1977. Why was that question so weighty? And why have I remembered the saga from which it springs over 40 years now, to pass it along to future generations of malacologists?

Previously, on the FWGNA blog! In December and January, we obsessed at great length over Lithasia geniculata, with its three subspecies, extending down the 275 mile length of the Duck River of Middle Tennessee, bearing smooth, oblong shells in the headwaters, developing robust, bumpy shoulders in the lower reaches. In his seminal (1940) monograph [1], Calvin Goodrich also identified a second species of Lithasia in the Duck, bearing a more acute apex and angled (sometimes even tuberculate) shell, extending only from about river mile 186 to the mouth. These he identified as Lithasia duttoniana.

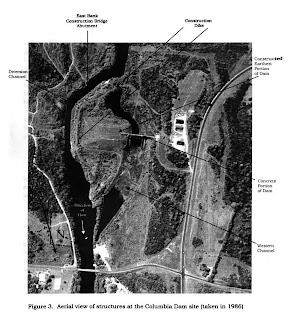

This month’s episode begins in Washington, as a whispered exchange in the hallowed halls of Congress. In 1969, just before the dawn of the environmental movement, federal funding was secured for the construction of two new dams on the Duck River: the smallish Normandy Dam at RM 248, and a larger and more expensive Columbia Dam, downstream around RM 145. The Normandy Dam was completed in 1976.

|

| Normandy Dam (TVA) |

But the National Environmental Policy Act went into effect January 1, 1970, the Clean Water Act in 1972, the and the Endangered Species Act in 1973. The TVA found itself required to file an environmental impact statement for the Columbia Dam, even as its construction proceeded apace. And Dr. George M. Davis, fresh out of the Army and sitting in the Pilsbry Chair of Malacology at the ANSP, was awarded a contract to survey the Duck for potentially endangered pleurocerid snails.

George Davis’ pleurocerid taxonomy was idiosyncratic. He began by noticing that in almost all aspects of their biology, including body size, life habit, and shell morphology, pleurocerid populations of the Haldeman's 1840 genus Lithasia are not strikingly different from Lea's monotypic genus Io of 1831. Davis therefore synonymized Lithasia under Io and recognized five taxa in the Duck River: Io geniculata geniculata, Io geniculata pinguis, Io salebrosa, Io armigera duttoniana and Io armigera jayana. The identities of Davis’ Io geniculata geniculata, Io geniculata pinguis, and Io armigera duttoniana will by now be obvious to my readership. “Io salebrosa” was Davis’ name for what Goodrich would have called Lithasia geniculata fuliginosa. What was “Io armigera jayana?”

The idea that a pleurocerid population matching Isaac Lea’s nomen “jayana” in the Duck River was especially controversial when Davis filed his report in 1974 [2]. Isaac Lea [3] published its brief, Latinate description in July [4] of 1841: “Hab. Cany Fork, DeKalb Co., Tenn. – Dr. Troost [5].” In his more complete English description of 1846, Lea emphasized “It very closely resembles the M. armigera (Say), in most of its characters, but may at once be distinguished by the double row of tubercles, the armigera never possessing distinctly more than one row [6].”

Lea’s selection of Mr. Say’s Melania armigera as a point of comparison is especially significant. Described by Thomas Say in 1821 from “The Ohio River” [7], the range of populations today identified as Lithasia armigera extends through much of the lower Cumberland and Tennessee Rivers as well [1], including the Tennessee at the mouth of the Duck. And the resemblance between Mr. Lea’s jayana and Mr. Say’s armigera is indeed close, as shown in the montage of Tryon’s [8] figures below.

|

| Two L. armigera left, two L. jayana right [8] |

The scene now shifts to the sleepy little East Tennessee company town of Norris, were in 1974 the TVA hired a promising young biologist named Steven A. Ahlstedt to work in its Department of Forestry, Fisheries, and Wildlife Development [10]. Steve is an excellent scientist, with superb field skills and a great eye for freshwater mollusks. He had a reprint of Tryon’s monograph on his shelf, and all of Goodrich’s papers in the top drawer of his filing cabinet, but very little of Goodrich’s work is illustrated, and to match Goodrich with Tryon is a bitch. And this was six years before the EPA published The Gospel According To Jack Burch [11]. So the TVA sent Steve to the University of Michigan Museum of Zoology to learn freshwater malacology hands-on.

And the stage is now set. In the fall of 1975 the telephone rang on George Davis’ desk at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. It was the receptionist downstairs. She reported that a team of TVA biologists had presented themselves at the front door and were requesting admission to the Malacology Department to examine his Duck River pleurocerid collections. They had no appointment.

|

| Two L. duttoniana [8] |

The members of the TVA team were John Bates, Billy Isom, Steve Ahlstedt and Donelly Hill. Bates was, at that time, a professor at Eastern Michigan University and Research Associate at the UMMZ [12]. Isom worked for the TVA at their Muscle Shoals office [13]. Hill was a supervisor, with a fisheries background.

Like my Momma used to say, “You could have called.” George Davis was still livid about the surprise nature of this audit when he told me the story two years later. The TVA team asserted that they had a right to examine the Duck River collections, since the agency they represented had paid for them. Davis countered that he would need reimbursement for the time required by his curatorial staff to pull the lots. The TVA team went away threatening to get a court order but returned the next day with a purchase order instead.

Davis would not admit either Bates or Isom into the collection. They were notorious guns-for-hire in the wild west era of American freshwater malacology, and Davis did not trust them. Neither did Steve Ahlstedt, for that matter. So, in the end, Donelly Hill sent the most junior member of the team, alone, up the elevator into the ANSP malacology collection to face the Wrath of George. Steve tells me that he felt like he was “caught between the ham and the cheese.”

At high noon the fateful shot rang out over Benjamin Franklin Parkway, “Well, Ahlstedt, is this jayana or is it not?” And Steve’s reply was … (dramatic pause)… affirmative.

The lower reaches of the Duck River, from about RM 60 to the mouth, are indeed inhabited by a population of Lithasia bearing shells indistinguishable from type collections made of L. jayana in the Caney Fork. And since Isaac Lea and his contemporaries defined gastropod species by shell morphology alone, and since the Duck shells in George Davis’ right hand matched the Caney Fork types, they were, by definition, Lithasia jayana.

So, Davis’ pleurocerid identifications stood. And in 1984, after a ten-year period of comment, revision and study, his taxa were included in a gigantic laundry-list of candidate invertebrates offered for review by the USFWS as Lithasia jayana, L. duttoniana, L. geniculata, L. pinguis, and L. salebrosa [15]. Nothing ever came of that proposal, however, and Lithasia jayana receded back into sincere obscurity, as opposed to the mere obscurity it had enjoyed in the 1970s.

|

| The abandoned Columbia Dam, 1986 [14] |

But it did not matter. By that point, Steve Ahlstedt and his colleagues had documented populations of genuinely-endangered unionids in the Duck – species that had already been entered into the Federal list, as early as 1977. Construction was halted on the 90% complete Columbia Dam in 1983, never to resume. According to Steve, “They left their coffee cups on their desks.” The $83M project was demolished in 1999, and the 12,800 acres it was planned to inundate turned over to the state wildlife resources agency.

But although the name of Lithasia jayana disappeared from the public eye, it remained printed in the pages of dusty tomes, and scrawled on the labels of moldering museum collections. And in 2003 our colleagues Russ Minton & Chuck Lydeard pulled it back from sincere obscurity into mere obscurity once again in the paper we reviewed early last month [16]. Russ and Chuck reported no mtDNA sequence divergence between the robust, doubly-spined populations that Davis identified as jayana and more lightly shelled populations, tuberculate at best, that Davis (and everybody else prior to 2003) identified as Lithasia duttoniana.

Nor is there any allozyme difference between jayana and duttoniana. Late last month I posted an unusually technical report on this blog, which I did not advertise at the time, so most of you probably missed it. If you’re serious about the science, you might want to open this link in a new window [28Mar22]. Or you could just scroll down directly below the present post, skim that essay and scroll back. Or you could just believe the paragraph that follows.

When Paul Johnson sent me all those Lithasia samples from the Duck River back in the summer of 2002, there were three bags from Site E and three bags from Site F – one labelled L. geniculata geniculata (which we talked about in December, January, and early March), one labelled L. duttoniana (which we talked about in January, early March, and late March) and one labelled L. jayana. Using gene frequencies at three allozyme-encoding loci, I was indeed able to distinguish L. geniculata from L. duttoniana. But there is no genetic distinction whatsoever between L. duttoniana and L. jayana. They seem to be simple shell forms of the same biological species.

So now the time has come to sum up, over all five essays in this extended series. The Duck River is inhabited by two biological species of large-bodied pleurocerid snails referable to the genus Lithasia. One of those species bears smooth, high-spired, shells in the headwaters, becoming more robust, oblong and bumpy downstream and out into the main Tennessee River. The modern era of American malacology was born in 1934, when Calvin Goodrich realized that populations bearing all those smooth-to-bumpy shells are conspecific, lowering the specific nomina assigned to two upstream forms, pinguis and fuliginosa, to subspecific status under the downstream nomen Lithasia geniculata.

|

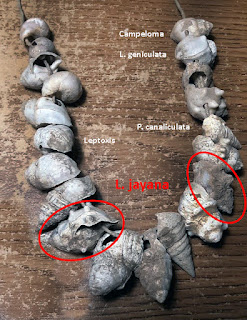

| Gastropod magafauna of Caney Fork, 500 A.D. [17] |

Living together with Lithasia geniculata in the lower reaches of the Duck River is a second species of Lithasia, genetically quite similar to L. geniculata, but morphologically distinct and reproductively isolated. These snails also demonstrate a cline in shell morphology, from a single row of light tubercules upstream, becoming more robust and heavily (even doubly) spined downstream, out into the main Tennessee River. Then by analogy with L. geniculata, let us lower the specific nomina assigned to the two upstream forms, duttoniana and jayana, to subspecific status under the downstream nomen Lithasia armigera.

This hypothesis is supported by the genetic data, both by the duttoniana/jayana allozyme results offered late last month [28Mar22], and by the L. armigera CO1 sequences published by Minton & Lydeard, reviewed early last month [3Mar22]. It was originally suggested on the basis of shell morphology by Calvin Goodrich himself, way back in 1921 [18], although by 1940, he had apparently changed his mind [1]. It was also advocated by Davis in 1974 [2].

So this morning I have uploaded three fresh pages to the FWGNA website: Lithasia armigera duttoniana, L. armigera jayana, and L.armigera armigera. And I remind my readership that the FWGNA defines the word “subspecies” to mean “populations of the same species in different geographic locations, with one or more distinguishing traits.” This is the definition of the term as developed by the architects of the Modern Synthesis, and means precisely what it says, neither more nor less [19].

There need be no additively-genetic basis for the “distinguishing traits.” Indeed, in the genus Pleurocera, a very closely analogous trend from gracile shells in the headwaters to robust shells in the big rivers has been convincingly attributed to cryptic phenotypic plasticity [20]. The heritable component of the shell morphological variance among populations identifiable as jayana, duttoniana, and armigera (s.s.) remains an open question.

Notes

[1] Goodrich, C. 1940. The Pleuroceridae of the Ohio River drainage system. Occasional Papers of the Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan 417:1 - 21.

[2] Davis, G.M. 1974. Report on the rare and endangered status of a selected number of freshwater Gastropoda from southeastern U.S.A. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Washington, DC. 51 p.

[3] For more about “The Nestor of American Naturalists” see:

- Isaac Lea Drives Me Nuts [5Nov19]

[4] Lea, I (1841) Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 2 (19): 83. There has historically been much controversy regarding the exact publication dates for Lea’s descriptions. The date on the cover of PAPS 2(19) is “July – October 1841,” a four month window. Lea’s description of jayana appears in the “Stated Meeting of July 16,” prefaced by a statement that the paper itself was “read on the 18th of June last.” That’s as far down the rabbit hole as I care to go.

[5] For a brief biography of Gerard Troost, see:

- On the Trail of Professor Troost [6Dec19]

[6] Lea, I (1846) Continuation of Mr. Lea’s paper on fresh water and land shells. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 9(1) 1 – 31.

[7] Say, T. (1821) Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia (First Series) 2: 178.

[8] Tryon, G. W. (1873) Land and Freshwater shells of North America Part IV, Strepomatidae. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections 253: 1 - 435.

[9] Lea, I. (1841) Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society Volume 2(16) 15.

[10] I met Steve in 1975, the summer after my sophomore year at Virginia Tech, when I was blessed to be offered an hourly job with the TVA in Norris. Malacological posterity will owe him a debt of gratitude for sharing his recollections of the events recorded here.

[11] This is a difficult work to cite. J. B. Burch's North American Freshwater Snails was published in three different ways. It was initially commissioned as an identification manual by the US EPA and published by the agency in 1982. It was also serially published in the journal Walkerana (1980, 1982, 1988) and finally as stand-alone volume in 1989 (Malacological Publications, Hamburg, MI).

[12] John Morton Bates (b. 1932) began his career at the ANSP 1956 – 1966, then accepted a tenured position at Eastern Michigan University, with a research associate appointment at the UMMZ. He left Michigan to found “Ecological Consultants” of Shawsville, VA, with Sally Dennis. I’m not sure what became of him after that.

[13] Billy G. Isom (b. 1932) was an ecologist for the Tennessee Stream Pollution Control Board 1957 – 1963 before joining the TVA as a supervisor in the Limnology Section at Muscle Shoals, AL. I think he is still alive and living in Killen, AL at the age of 89.

[14] Tennessee Valley Authority (1999) Use of Lands Acquired for the Columbia Dam Component of the Duck River Project. Final Environmental Impact Statement.

[15] Federal Register FR-1984-05-22. Endangered and threatened wildlife and plants; Review of invertebrate wildlife for listing as endangered or threatened species. 49(100) 21664 – 21675.

[16] Minton, R. L. and C. Lydeard. 2003. Phylogeny, taxonomy, genetics, and global heritage ranks of an imperiled, freshwater snail genus Lithasia (Pleuroceridae). Molecular Ecology 12:75-87. For my review, see:

- The third-most amazing research results ever published for the genetics of a freshwater gastropod population. And the fourth-most amazing, too. [3Mar22]

[17] This necklace was discovered by Cousin Bob Winters in a rock shelter on the north shore of Center Hill Reservoir, DeKalb County, TN.

[18] Goodrich, C. (1921) Something about Angitrema. The Nautilus 35: 58 – 59.

[19] If the clean, clear definition of the word “subspecies” confuses you, read:

[20] Cryptic phenotypic plasticity is defined as “intrapopulation morphological variation so extreme as to prompt an (erroneous) hypothesis of speciation.” For examples, see:

- Goodrichian Taxon Shift [20Feb07]

- Goodbye Goniobasis, Farewell Elimia [23Mar11]

- Pleurocera acuta is Pleurocera canaliculata [3June13]

- Elimia livescens and Lithasia obovata are Pleurocera semicarinata [11July14]

If you are citing authorship of a genus it is incorrect to place the author in parentheses. Parentheses intact a change of genus in a species name. It makes zero sense to use parens.

ReplyDeleteFixed. Thanks for keeping me on the straight-and-narrow.

Delete