Editor’s Note – This essay was subsequently published as: Dillon, R.T., Jr. (2023c) Character phase disequilibrium in the Gyraulus of Europe. Pp 215 – 226 in The Freshwater Gastropods of North America Volume 7, Collected in Turn One, and Other Essays. FWGNA Project, Charleston, SC.

I get a lot of requests for freshwater gastropod samples for sequencing studies. And I confess, I can sometimes be a jerk about it. In reply, I always ask, “What hypothesis do you plan to test?” Note that answers of the form, “I want to work out the phylogeny of gastropod family X” or “I want to figure out how many species there are in the gastropod genus Y” do not qualify as hypotheses [1].

So back in October of 2020 I was pleased to receive an email from Jeff Nekola of Masaryk University in Brno, the hometown of Gregor Mendel, posing a very well-considered hypothesis to test with sequence data from specimens that I might provide him. Jeff introduced me to his colleague Michal Horsak, and the two of them together pitched me a project to test whether their European Gyraulus laevis (Adler 1838) might be conspecific with our North American Gyraulus parvus (Say 1817). Let’s back up for a bit of context.

|

| G. laevis [4] |

So G. laevis and G. parvus were both among the eight European species recognized as valid by Prof. Meier-Brook, the former ranging widely across Europe but “rather stenotopic and rare.” The latter he considered native in Iceland, but introduced into Germany by the early 1970s, and rapidly spreading through Europe as he wrote his monograph.

The two species are quite difficult to distinguish in the field, and even as early as 1952 European workers were suggesting that laevis might be a junior synonym of parvus [7]. Meier-Brook disagreed. And here is the couplet by which he suggested that we distinguish them, transcribed verbatim:

6A. Penultimate whorl distinctly elevated, distal portion of spermoviduct slender, not wider than widest portion of sperm duct; distal half of vas deferens much wider (2:1 on an average) than proximal half (introduced from N America)… G. parvus.

6B. Penultimate whorl not or not distinctly elevated, distal portion of spermoviduct wider than widest portion of sperm duct and vas deferens, distal half of vas deferens not conspicuously widened (1:1) … G. laevis.

The six samples of G. parvus upon which Meier-Brook based his diagnosis, however, were collected from Ann Arbor, two places in Canada, two places in Iceland, and Germany – none from Thomas Say’s type locality in the Delaware River near Philadelphia. So the hypothesis advocated by my colleagues in Brno back in October of 2020 was an interesting one, and it did, indeed, seem likely to me that sequence data might cast some light upon it.

And my loyal readership may remember an expedition I undertook up the Delaware River in 2012, hunting the type locality of Thomas Say’s Lymnaea catascopium [8]. I had picked up incidental samples of G. parvus at two sites on that field trip, which I agreed to post to Brno at my next opportunity.

|

| G. parvus [4] |

Jeff and Michal also asked if I might be able to spare a couple samples of Gyraulus circumstriatus. My antennae raised slightly at this request – it was hard to see how sequence data from G. circumstriatus might bear on the hypothesis before us. And all I had on my shelves was a couple odd samples from Montana and NW Pennsylvania, nowhere near the Connecticut type locality. But OK – in for a penny, in for a pound [9].

So in late January of 2021 I was pleased to receive an email from Michal reporting success in sequencing the samples that I had sent, and that “the preliminary phylogenetical analysis clearly says that these are the same species and there is also no difference from all European populations of G. parvus/laevis.” And in mid-April a first draft manuscript arrived, courtesy of Ms. Erika Lorencova, the lead author on the project.

I found some things to like about the research as the manuscript unfolded before my eyes last spring. Lorencova, Nekola, Horsak, and five additional coauthors [10] had sequenced four genes (COI, CYTB, ITS1, ITS2) from 65 individual snails representing seven nominal species of Gyraulus, plus a Planorbis outgroup – just one single individual per population, in almost all cases, alas. They did not sequence all four genes for all 65 individuals, alas again. Their data set included 34 individuals identified as G. parvus (27 Czech, 2 Slovak, 1 Croat, 1 Aust, 1 Serb, 2 USA) and 14 individuals identified as G. laevis (12 Czech, 2 Croat), none of the latter collected from anywhere near Alder’s type locality in England, which pissed me off royally. Their data set did, however, include one individual collected from Scotland, one from Northern Ireland, and two from Wales, all identified as “parvus/laevis,” none of which helped one little bit.

Erika and our mutual colleagues opted to analyze their (mitochondrial) COI + CytB dataset separately from their (nuclear) ITS1 + ITS2 dataset. They generated gene trees using four different methods for each data set: neighbor-joining, maximum parsimony, maximum likelihood, and Baysian inference, for a total of eight separate analyses. All of these “yielded very similar tree topologies.” If not, I suppose our friends in Brno could have picked the one they liked best.

|

| Fig 2 of Lorencova et al [16] modified |

|

| Tab 1. Gyraulus classified by species and mtDNA |

Shifting our attention to the nDNA tree at right, we find the percent sequence divergence much less, but the character phase disequilibrium even more significant. Lorencova and colleagues did not divide the gigantic branch at the bottom of their nDNA tree into “races” as they did for their mtDNA tree, but they easily could have done so. There seem to be just two ITS1+ITS2 races, rather than the three we saw for mtDNA, and they differ by only a couple nucleotides. But the match between the top half of the big branch of the nDNA tree is very close to the top half (“Race I”) of the big branch of the mtDNA tree. And ditto for the two bottom halves. Note that the same two individuals labelled “laevis” in the lower (Race III) clade on the mtDNA tree at left are exactly the same two individuals labelled “laevis” in lower clade by their nDNA at right, for example.

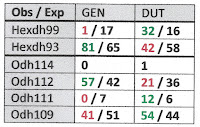

And indeed, laevis is again very much over-represented in the upper clade in the nDNA tree, which we might as well go ahead and call Race I, and parvus very much over-represented in the lower clade, which we might as well call Race III. For the nDNA, Table 2 below shows that the contingency chi-square is 12.89 (1 df), even more significant than the mtDNA results. What gives?

The 42 individual Gyraulus hanging on the big, low branches of the two gene trees shown above were not drawn from a single randomly-breeding population. In large and complexly-structured environments, such as Erika’s six-country sample area most certainly is, the first thought of an evolutionary biologist would be that any such non-random mating might arise from barriers to dispersal or isolation by distance. So let’s re-run our analysis focusing just on the 29 individual Gyraulus collected from the Czech Republic. The mtDNA breakdown is Race I parvus = 5, Race I laevis = 11, Race III parvus = 11, Race III laevis = 2, chi-square (1 df) = 8.26, still quite significant.

|

| Tab 2. Gyraulus classified by species and nDNA |

I suppose it is possible that there might be some sort of geographic structure in the 29 Czech samples below the level of the country in which they were sampled, but I do not have the patience to plot 29 sets of lat/long coordinates and look for it. I will simply note that there is another very plausible explanation for the character phase disequilibrium apparent in the branches of the gene trees developed by Erika, Jeff, Michal and our mutual colleagues, beyond some sort of fine geographic structure that I cannot see. Perhaps the two sets of populations they have identified as G. parvus and G. laevis are in fact good, biological species, genetically and morphologically similar but reproductively isolated, with a smattering of misidentifications [13] or a hybridization event here and there. In any case, the results of Lorencova et al. (2021) do not support their hypothesis that G. parvus and G. laevis are conspecific.

All through the second half of the month of April I carried on a detailed and earnest email correspondence with my colleagues in Brno, desperately trying to get them to see the reasoning I have outlined in the seven paragraphs above. I explained character phase disequilibrium every way I know how to explain it, backing all the way up to Mendel and coming forward, drawing diagrams with circles and arrows and a paragraph on the back of each one explaining what each one was [14]. I calculated probabilities to the fourth decimal place and highlighted them in bold. And I simply could not make Jeff, Erika, or Michal understand character phase disequilibrium, or its origins in non-random mating, or the likelihood that the disequilibrium evident in the branches of their trees might reflect reproductive isolation, or indeed (in retrospect) the connection between reproductive isolation and speciation.

Alas, we seemed to be speaking different languages. Rather than the term, “species,” my colleagues preferred the term, “species-level clade.” And they concluded that G. parvus and G. laevis were “part of the same species-level clade” because “although reasonably well-supported races exist in the mtDNA tree their base pair variability is three times smaller than that seen between the other analyzed Gyraulus species” [15].

Nor apparently could the editor of the international journal to which my colleagues submitted their paper see the character phase disequilibrium in their Figure 2 as modified above, nor understand its significance, nor apparently could the reviewers he chose. Apparently, there is widespread blindness in evolutionary biology today to simple principles of transmission genetics that I have considered fundamental for my entire professional career. The paper by Lorencova and colleagues was published in July [16]. Going beyond their proposed synonymization of G. laevis under G. parvus, our colleagues in Brno went so far as to suggest that “North American G. circumstriatus might simply represent another race within G. parvus.” Good grief.

Well, science is a self-correcting process. Someday some bright young student will realize that the answer to the parvus/laevis question does not lie in sampling a single individual from 30 populations, but in sampling 30 individuals from a single population. He will find a lake or a pond inhabited by Gyraulus bearing both the Race 1 and Race 3 haplotypes [17]. He will collect and sort 30 adults by the elevation of their penultimate shell whorl, sequence those genes, and look for disequilibrium between mtDNA race, nDNA race, and shell morphology. And here is his hypothesis: big excesses of Race 1/flat whorl and Race 3/elevated whorl. Will our bright young student find any Race 1/elevated or Race 3/ flat recombinants? Will he find any ITS heterozygotes? Good questions.

I will conclude with a caveat. I am not aware of any research directly bearing on mode of reproduction in Gyraulus, but my biological intuition suggests to me that populations of trashy, weedy planorbids such as G. parvus most certainly is might demonstrate significant frequencies of self-fertilization. Asexual reproduction voids the biological species concept and necessitates a retreat to the solid rock of morphology, not a blundering-forward into the slough of DNA [18].

So if our bright young student of the future confirms preferential selfing in Gyraulus, and googles up this essay and reads it, I would ask him to go back to my essay of [4Jan22], read to note [3] and stop. The first nine paragraphs of my January essay will have turned out to be important for Gyraulus, but the remainder not. And then I would suggest that he come forward to the present blog post, re-read from the top of my essay to Claus Meier-Brook’s couplet distinguishing G. parvus and G. laevis morphologically, and then stop again. Because none of the rest of this month’s post will have turned out to be relevant, either. To the extent that Gyraulus populations self-fertilize, Professor Meier-Brook’s brilliant 1983 monograph stands as the final word thus far.

Notes

[1] If, however, the opening lines of the present essay happen to fall upon the eyes of a bright young student with access to a molecular lab and an interest in real science [2], I stand ready to help in any way I can. I even have a list of genuine hypotheses about the evolution of freshwater gastropods ripe for testing with sequence data, for students in the market for thesis topics. A long list.

[2] Science is the construction of testable hypotheses about the natural world.

[3] Claus Meier-Brook (1934 - 2018) has occupied a niche in my malacological pantheon since the dawn of my professional career. I never met him, although we enjoyed a cordial correspondence in the 1980s. He was best known for his work on pisiidid clams, but also made important contributions to our understanding of the medically-important planorbids. He was unable to resist the Willi Hennig fad, alas, but the cladist gobbledygook is easy to subtract from his otherwise inspiring oeuvre [5]. For a biography and bibliography, see:

- Jungbluth, J. H. (2006) Claus Meier-Brook 70-Jahre (28 April 1934). Mitteilungen der Deutschen Malakozoologische Gesellschaft 75: 39-47.

[4] Meier-Brook, C. (1983) Taxonomic studies on Gyraulus (Gastropoda: Planorbidae). Malacologia 24: 1 – 113.

[5] And I feel like Salieri. Rifling the pages of his papers, hearing the beauty of the science in my mind’s ear – a rusty squeezebox, high above it a single oboe – my heart breaking. But jeeze, crap! Hit the fast-forward button through Movement VI, Cladiste.

[6] Meier-Brook recognized six Gyraulus species endemic to Macedonian lakes.

[7] Jaeckel, S. (1952) Zur Oekologie der Mollusken-fauna in der westlichen Ostsee. Sctiriften des Naturwissenscfiaftlictien Vereins fur Sctileswig-Holstein. 26: 18-50.

[8] It is traditional to assume that Thomas Say’s type localities for both G. parvus and L. catascopium were in the Delaware River at his home town of Philadelphia. But 200 years of commercial development at the Philadelphia waterfront have rendered that environment unrecognizable today. For an account of my explorations upstream, see:

- The Type Locality of Lymnaea catascopium [14July15]

[9] Or more accurately, “In for 200 mg of snail flesh, might as well go all in for a half gram.”

[10] Michal offered me a coauthorship, which was very considerate of him, and I did appreciate the honor, but ultimately declined.

[11] MtDNA sequence divergences in the 4 – 5% range are quite consistent with the values typically reported among valid, biological species of freshwater pulmonate snails. But that is not the direction I want to go in the present essay.

[12] The two G. circumstriatus sequences, sampled as they were from Montana and British Columbia, geographically remote from all 40 of the samples of parvus and laevis available for comparison, have no bearing on the specific status of circumstriatus whatsoever.

[13] Meier-Brook considered G. laevis and G. parvus sibling species, which means that they cannot be distinguished morphologically, and then spent many pages developing evidence to the contrary, ironically.

[14] By now I imagine that the origin of last month’s blog post will have become obvious to my perceptive readership. My essay of 4Jan22 was an adaptation of the extensive email correspondence I carried on with Jeff Nekola and Michal Horsak in April of 2021. And the reason for all those examples involving Mendel’s peas was that I was trying to communicate with geneticists in Brno. And vainly searching for a language that we might have in common. See:

- What is character phase disequilibrium? [4Jan22]

[15] Darn it, I know I said in footnote [11] that this is not a direction I want to go with the present essay. But it’s eating at me. Although the “base pair variability” observed among the laevis, parvus, and circumstriatus clusters may indeed be “three times smaller than the values seen between the other analyzed Gyraulus species,” the values of 4 – 5% mtDNA sequence divergence among those groups reported by Erika, Jeff, Michal and colleagues are NOT small when compared to interspecific values typical for biological species of freshwater pulmonates worldwide. See, for example:

- The Lymnaeidae 2012: Stagnalis yardstick [4June12]

[16] Lorencova, E., L. Beran, M. Novakova, V. Horsakova, B. Rowson, J. Hlavac, J. Nekola, and M. Horsak (2021). Invasion at the population level: a story of the freshwater snails Gyraulus parvus and G. laevis. Hydrobiologia 848: 4661 – 4671.

[17] A clean answer to the question that has sent nine scientists, including yours truly, scampering around the world to not answer may be waiting 60 km south of Brno. For according to the supplementary materials available with their paper, Erika, Michal, Jeff & Company did collect snails they identified as both parvus and laevis together in a fishpond on the northern edge of the Czech town of Hlohovec.

[18] I vividly illustrated the folly of attempting to classify asexually-reproducing populations by DNA sequence data in two recent series of blog posts: one on the (parthenogenic) prosobranch Campeloma and a second on the (self-fertilizing) pulmonate Galba. See:

- Fun with Campeloma! [7May21]

- What Lymnaea (Galba) schirazensis is not, might be, and most certainly is [3Aug21]